The Battle of Zama

On October 19th, 202 B.C., the plains of Zama (the present-day Saqiyat Sidi Yusuf, Tunisia) were teeming with soldiers as they prepared for the deciding battle which would mark the end of the long Second Punic War. The two grim enemies, Hannibal, from Carthage (modern day Tunisia, north Africa) and Scipio, from Rome, stared at each other’s armies, analyzing every extra soldier. Hannibal had, Scipio noted, eighty imposing, impatiently fidgeting, and half-trained elephants. Scipio shuddered as he imagined his soldiers trampled, crushed to death, under the 10,000-pound weight. Putting the elephant’s enormity out of his mind, Scipio bent and twisted his neck, trying to see the footmen behind the towering elephants: from what he could glean, Hannibal had about 35,000-40,000 footmen and 3,000 cavalry, a reasonably good amount. Scipio smiled inwardly (it was never a good idea to show your feelings before a battle) seeing that Hannibal’s first line of men were frightened recruits that had likely just been picked up along the way. Scipio’s soldiers had bulging muscles, hard, chiseled features, and fierce, determined eyes. Scipio felt a twinge of fright, though, about what must be skilled, decorated veterans at the back. Although Scipio couldn’t see the third line of soldiers, he was relatively sure Hannibal had put them in the traditional three lines, with the skilled at the back and the inexperienced at the front.

Scipio himself had the same formation, with what the Romans named hastati, principes, and triarii, in order. The triarii were the skilled, wealthy men, the ones at the back everyone depended on. The principes were the middle class, reasonable in skill and wealth. The hastati were poor and unskilled, put at the front because they were worth risking, however, their long javelins, called pilums by the Romans, could go clean through the enemy. Instead of forming the traditional checkerboard lines, though, Scipio had left vacant spaces between the soldiers. He looked back, and was satisfied at seeing the silver gleam of the swords and shields abruptly changing into the light green of frost-covered grass. These spaces weren’t completely empty: there were spry, light-footed skirmishers, known as velites by the Romans, bows at the ready, dotted throughout the columns, who were, like Scipio, scorning Hannibal’s puny cavalry. Scipio’s cavalry were strong, agile, and had massive numbers compared to Hannibal’s. On that good note, Scipio, satisfied, sat back on his horse and told himself relatively confidently that he had a slight advantage. But then his thoughts were interrupted at Hannibal’s resounding battle cry, and Scipio, along with everyone, sprang into action.

The fate of the two most powerful empires of the time balanced on this renowned Battle of Zama. One side would win, and extend into one of the largest empires of all time. One side would fall, shrivel up under the light of the winning empire, and eventually die. These two prodigious adversaries were Carthage and Rome. Carthage, a sprawling African empire, was the trading center of the world; thousands of people flocked to the beautiful sun-browned country to chat and barter and laugh in the huge marketplaces. Rome, a vast empire centered in what is now Italy, was splendid and beautiful in its white columns and smooth arches. Rome was a blossoming flower, and yet Carthage was in full bloom, a beautiful white lily that towered over Rome.

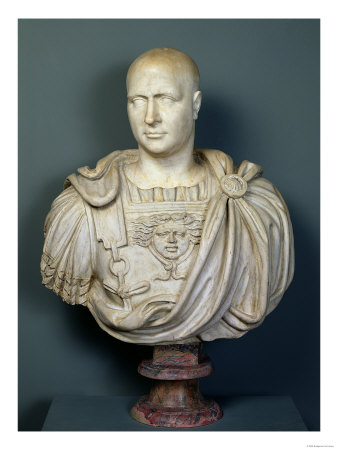

The person who took credit for Carthage’s domination was Hannibal, Carthage’s victorious leader. Hannibal had been raised by his illustrious father, Hamilcar, to be a great general, beginning his military career thirty-five years before the Battle of Zama, at the tender age of ten. When Hamilcar died, Hannibal had been ready. He had then taken his first solo step out of Carthage, proceeding to conquer every Roman land he’d stepped into. Over the next twenty-five years, Hannibal swelled Carthage’s already huge territory into an enormous one, and shriveled Rome’s reach. All the mighty generals of Rome were now buried in battlefields, leaving nobody left to rule Rome’s military. However, a young noble Roman, Scipio, had seized his chance and declared himself leader. Scipio: “who was he?” murmured the Romans. And soon, from countless rumors, they found out. Scipio, aha! He was a young, intelligent Roman who could turn out to be Rome’s formidable messiah, or yet another inexperienced, vanquished general.

Hannibal was known across the continents for his almost spotless battle record. What made it twice as amazing was that Hannibal never won by a huge army but always by an ingenious strategy. And the second-most famous battle in the Second Punic War, the Battle of Cannae, is a great example. The strategy of the Battle of Cannae would tip the scale in the Battle of Zama, but in whose favor?

The Battle of Cannae took place 14 years prior, in 216 B.C. By this time, the Roman senate had had enough of defeated armies and dead generals. To prepare for this battle, the senate had recruited thousands of men and built up a huge, towering army to rival Hannibal’s. Hannibal, at this battle, wasn’t worried. He had his brain, a couple of soldiers, and that was all he needed. He arranged his soldiers in a wide semi-circle, (the outward part facing the Romans), with the cavalry and some other foot soldiers in the front of this semi-circle. The Romans had scorned this seemingly pointless strategy and had laughed as the soldiers retreat rapidly, not knowing those soldiers had been told to do so. And when they finally realized, it was too late. Hannibal’s soldiers bounced back from facing outward to an inner-facing semi-circle, their cavalry moved in front of the Romans, and the Romans were enveloped. Surrounded by all sides, the Romans, helpless, defeated and shamed, were destroyed.

It was fourteen years later, and Scipio was fresh, new, perhaps inexperienced, a young confident man taking the dead generals’ charges. Hannibal was experienced, wise, perhaps tired; he had already lost an eye. These two were enemies from birth. There’s a legend that Hannibal’s father made his son take an oath to always be an enemy of Rome. And isn’t it said, “Keep your friends close and enemies closer”? It is extremely likely that every Roman military man studied Hannibal’s tactics. Scipio did so himself, studying many of Hannibal’s victorious battles, including the Battle of Cannae. And later, he was able to claim not just studying, but mimicking one of those battles. Hannibal, because of his fame, whether he liked it or not, was a teacher to his enemy.

The preparations for the Battle of Zama had been frustrating, but Scipio was careful to hide this frustration as he trained his troops. Syphax, a Numidian king with a formidable army, wasn’t going to be his ally when the time came to fight Hannibal. The reason was a beautiful, Carthaginian woman, Sophonsiba, who easily persuaded her new husband to help Hannibal instead of Scipio. Luckily, though, Scipio secured the help of another Numidian king, Syphax’s rival, Masinissa. But because Syphax had destroyed most of Masinissa’s land and people, Massinissa could only contribute about 1,000 cavalry, who were on their way.

Meanwhile, Hannibal was worried. Yes, he’d gotten some of Syphax’s cavalry, but it wasn’t enough. If one of his brothers, Mago, could safely come over (which Mago was in the process of doing), Hannibal would have enough soldiers. But it was dangerous in wartime. Hannibal had already asked his other brother, Hasdrubal, to contribute, and Hasdrubal and his army had marched over. But Scipio had intercepted Hasdrubal, and he and most of his army had lost their lives. Mago’s forces were traveling on ship, Hannibal’s army on foot, to join armies. But, when they met, Hannibal learned that Mago’s army had lost many soldiers, including Mago himself, from a skirmish at sea with the Romans. These were Hannibal’s brothers, two experienced generals, now dead, unable to help Hannibal in a battle where he might end up dead himself. But there were still some reinforcements, about 12,000 men that joined Hannibal’s army. These were Ligurian and Celtic mercenaries, picked up along the journey from Carthage.

Hannibal caught wind of Masinissa becoming an ally of Scipio. He knew that Masinissa was coming to help Scipio in the looming battle. He quickened the army’s pace; they would have the advantage if they battled against Scipio before the reinforcements arrived. But Hannibal was too late: Masinissa had arrived with his skilled cavalry. Hannibal was forced to admit Scipio had a slight advantage.

Legends tell that, just before the battle, Hannibal and Scipio met for the first and only time, most likely out of curiosity. This was probably the only time they met, Scipio’s wrinkle-free face cold and stony, secretly admiring Hannibal whose strategies he could recite by heart. Hannibal’s face was as stony and cold as Scipio’s, but he admired the young, brilliant energy in the young general’s face. Despite the hidden admiration, though, there was an unmistakable tension in the air, an almost tangible fear and rivalry. They were enemies, after all.

Far away from the mountains, people felt the vibrations from the hundreds of army elephants, who, on cue, had responded to Hannibal’s cry in this Battle of Zama. The elephants stampeded forward, each vibration making every footman flinch. But as soon as the elephants took one step toward the Roman army, Scipio’s trumpeters raised thousands of trumpets and blasted a great, big, ugly, out-of-tune sound and the elephants, susceptible to noise, became paralyzed. Scipio needed to do only one more thing to get them to move out of the way. At a thunderous cry, the skirmisher’s light arrows started to pierce the elephants and they went berserk. Some galumphed crazily into the left side of their own flanks, causing that side to go into complete disarray. Others took the wise course and ran through the purposely-put gaps between Scipio’s soldiers, and were then free. Some elephants, though, did thrust themselves into Scipio’s army. Taking advantage of the confusion caused by the elephants, the Roman cavalry on the left flank galloped forward, chasing the army faster and faster away from the battlefield.

Knowing his cavalry was now too far away to save, Hannibal called his footmen forward, who started shouting valiantly to each other, to quench every scintilla of fear. They were able to fight and march their way through Scipio’s lines without too much difficulty, and the armies continued fighting. All the Roman soldiers felt a tangible, frightening fear of the humiliation, or worse, death, from losing the battle, but then new energy coursed through Roman veins, and they fought with brilliant zealousness through the first line. They marched on to the second line, slightly confident, slightly wary. Hannibal had to act quickly to thwart the Romans’ possible easy breakage through his lines. He ordered the second line to extend outward with the first line’s survivors, to keep the rows in formation. The second line, thinking that the remnants of the first line were running away, started attacking their own fellow soldiers!

Secretly laughing, Scipio’s army danced past. But the Romans were now tired and sweaty, with double cramps and tangled hair. Hannibal still had a reasonable chance of winning. Knowing that if Masinissa’s (Scipio’s ally, the Numidian king) cavalry came back before Hannibal could defeat the Romans, that Rome would definitely win, Hannibal ordered his third line to march and fight. The exhausted Romans had to fight off the best of Hannibal’s army.

Now it was Scipio’s turn to act quickly. In the split second before the armies clashed, Scipio ordered his line to extend, in response to Hannibal doing the same. Now, both sides formed opposing long lines. The two enemies marched forward again, shouting to keep their energy up, and then suddenly stopped mid-step. Time stopped, the whistling wind stopped, the shouts and the cries stopped, the clashing swords stopped, everything stopped… everything except the sound of thousands of galloping hooves whose sound filled up the whole valley. Emotions escalated and plunged at this huge sound, zigzagging through the confused, dumbstruck soldiers. Masinissa’s cavalry, though, had only one emotion, a need really, a need to gallop on faster and faster until they could reach the battlefield and destroy. Finally, sweaty and determined, Masinissa’s cavalry swooped over the hill. The cavalry’s dark shadow was cast over the thousands of soldiers. Masinissa paused for a moment, staring at the thousands looking up at him. Masinissa snapped out of his reverie, and his army charged down the hill, ramming into the back of Hannibal’s soldiers. The Carthaginians helplessly turned in circles, fighting with the cavalry in back and with Scipio’s foot soldiers in front. But it was impossible to do those two things at once. Surrounded by all sides, the Carthaginians, helpless, defeated, shamed, knew they had lost. The enemy was closing in, the soldiers were dropping like flies. Hannibal’s face fell in his one and only defeat, and he galloped off, tears stinging in his shocked, despairing eye.

Enveloped, trapped, and then destroyed: this happened twice in the Second Punic War, in its most important battles. In the first enveloping battle, the Battle of Cannae, two Roman generals fought Hannibal, and Hannibal won, using an enveloping strategy. In the second enveloping battle, the Battle of Zama, the victor was Scipio, the Roman. This battle ended the war. Scipio, using Hannibal’s enveloping strategy, won.