Tolkien’s Creative Process in The Lord of the Rings

“The realm of fairy-story is wide and deep and high and filled with many things: all manner of beasts and birds are found there; shoreless seas and stars uncounted; beauty that is an enchantment, and an ever-present peril; both joy and sorrow as sharp as swords.”

― J.R.R. Tolkien, “On Faerie Stories”

J.R.R Tolkien, one of the 20th century’s most impacting writers, was a man full of many great ideas, which couldn’t wait to get onto paper. Not surprisingly, Tolkien could not have written fairy-stories, full of detailed plots, beautifully described terrain, and a multitude of realistic characters, without any inspiration. By understanding the origins of Tolkien’s ideas, one doesn’t discredit his ability as a writer, but rather allows for the great lengths Tolkien had to go through, to craft his compelling trilogy The Lord of the Rings, and its prequel, The Hobbit. Tolkien used many sources for inspiration that allowed him to broaden his imagination. Writing his trilogy not only became a passion and way to make money, but it also developed new languages and revived dead ones, expanding and defining the genre as a whole.

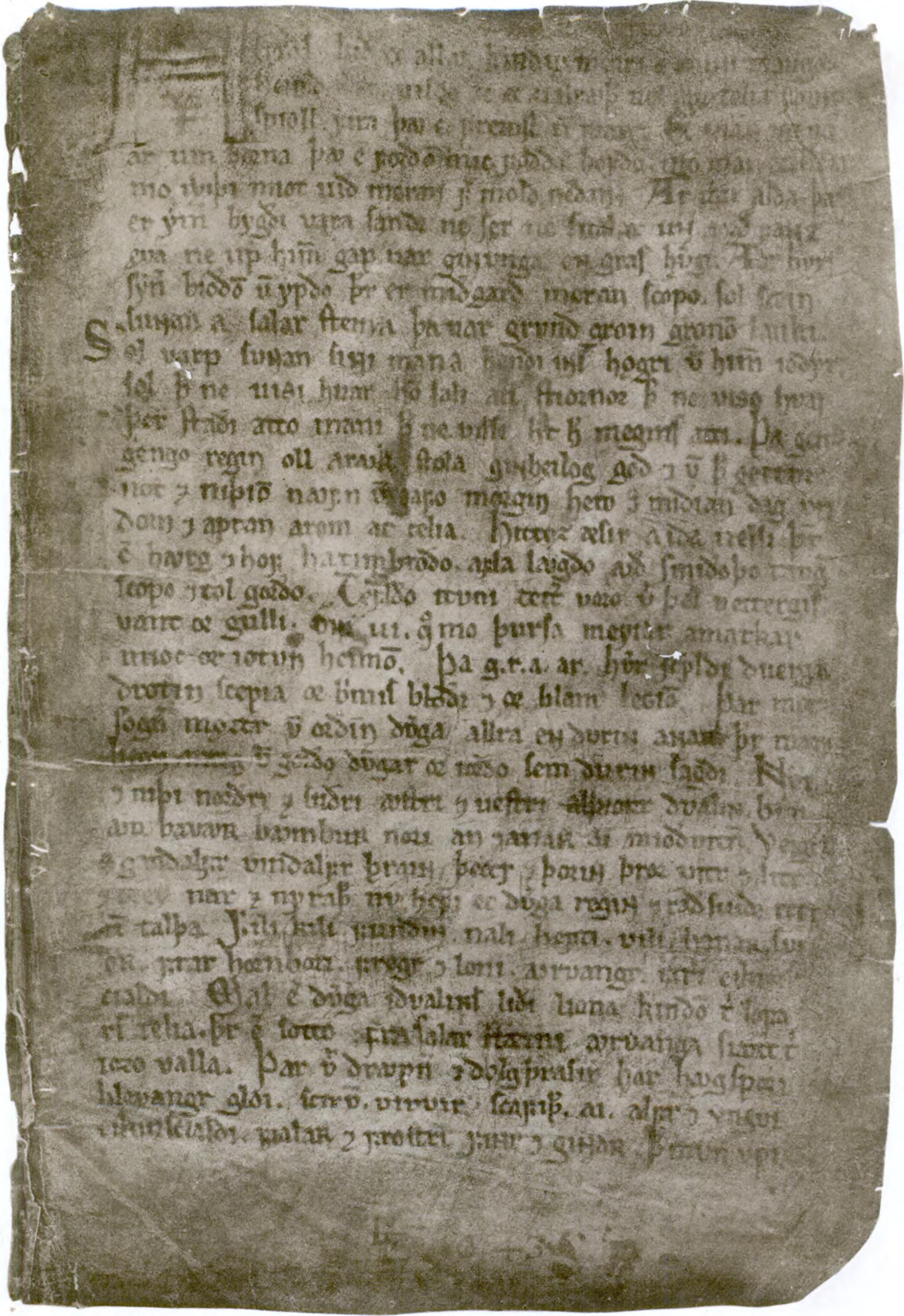

One of the inspirations in The Hobbit is the naming of the dwarves. When I first encountered the dwarves in The Hobbit, I was amused at their exotic names; never would I have known that Tolkien had based the names off of another piece of literature. Poetic Edda is a collection of mythological Old Norse poems, which has influenced writers, such as Karin Boye, Jorge Louis Borges, August Strindberg among others. The first poem in Poetic Edda, “Völuspá”, contains most of the names of dwarves in The Hobbit:

- Nyi and Nithi, | Northri and Suthri,

Austri and Vestri, | Althjof, Dvalin,

An and Onar, | Ai, Mjothvitnir.

Thekk and Thorin, | Thror, Vit and Lit,

Nyr and Nyrath,– | now have I told–

Regin and Rathsvith– | the list aright.

Hepti, Vili, | Hannar, Sviur,

(Billing, Bruni, | Bildr and Buri,)

Frar, Hornbori, | Fræg and Loni,

Aurvang, Jari, | Eikinskjaldi.

The Poetic Edda, Codex Regius Ms

“Völuspá” is the story of a woman who rises from the dead to tell the history of the Earth, including its creation, and about its dwarves and other life forms. Tolkien was fluent in twelve different European languages, and created his own Elvish language for The Lord of the Rings; his mastery of languages (he was familiar with 35) allowed him to read a wide range of literature in the original language, which revealed different historical and cultural messages. Tolkien probably encountered this poem in the original, and was able to translate it himself. Perhaps these names helped to determine other character names in the book. The use of ancient names emphasizes that names in Faerie stories can be common names from any time period.

The environment that Tolkien creates absorbs the imagination completely. It is extremely difficult to come up with the amount of environments in The Lord of the Rings from scratch. Tolkien grew up in Sarehole, Warwickshire.  He loved the barren terrain that surrounded him, and even the name made it into The Hobbit: “the Shire”. Rural areas in the UK and in Australia and New Zealand use the suffix ‘shire’, an equivalent to ‘county’. Warwickshire is a land full of intact vegetation, with minimal man-made structures. Rivers flow in Sarehole, still possessing their natural opaqueness, while trees surround it, appearing to not have been touched by a landscaper. Tolkien moved to Sarehole from South Africa at the age of 4 after his father had died.

He loved the barren terrain that surrounded him, and even the name made it into The Hobbit: “the Shire”. Rural areas in the UK and in Australia and New Zealand use the suffix ‘shire’, an equivalent to ‘county’. Warwickshire is a land full of intact vegetation, with minimal man-made structures. Rivers flow in Sarehole, still possessing their natural opaqueness, while trees surround it, appearing to not have been touched by a landscaper. Tolkien moved to Sarehole from South Africa at the age of 4 after his father had died.  Sadly, the town, which Tolkien held very dear to his heart, is no longer incorporated.

Sadly, the town, which Tolkien held very dear to his heart, is no longer incorporated.

After leaving Warwickshire for South Africa, and then Birmingham, he later returned for his wedding. Tolkien met his wife at the age of 16 and was married for 55 years. J.R.R and Edith Tolkien got married on March 22, 1916 in Sarehole’s Catholic church.

One of the most important inspirations that Tolkien encountered was from a fourth century Roman story The Vyne Ring; the story gave him ideas for The Lord of the Rings. Silvianus, the main character in The Vyne Ring, lived in ancient England, a Roman occupier of the land of Anglos and Saxons. Silvianus traveled to a temple. “During his visit (and possibly while Silvianus was bathing in the temple’s elaborate baths), his gold ring was stolen” (Forest-Hill). Much about him is unknown, but from the inscription on a tablet, historians know that he placed a curse on the ring and asked for the god Nodens to find the thief, and in turn, Nodens would receive half the value of it. In a fantastic stroke of luck, Silvianus’s ring was found in an archeological discovery by one of Tolkien’s colleagues, R.G. Collingwood.

Collingwood, a philosopher, archeologist, and historian, was a graduate of Oxford University, same as Tolkien. Collingwood’s most famous work, The Idea of History, is a philosophy of history; some say he is not acknowledged adequately, and is a very underrated thinker. He stated that studying history requires a different approach than studying natural science, because exact details are unknowable: one has to make educated guesses about what actually happened in days past. To do this, a historian has to put themselves in the place of people at the actual event, and go through similar thought processes that the person was likely to have. Collingwood believed that this was different than studying sciences. Tolkien, influenced by Collingwood, may have come to the same realization, and attempted to preserve history in his own writing.

is a philosophy of history; some say he is not acknowledged adequately, and is a very underrated thinker. He stated that studying history requires a different approach than studying natural science, because exact details are unknowable: one has to make educated guesses about what actually happened in days past. To do this, a historian has to put themselves in the place of people at the actual event, and go through similar thought processes that the person was likely to have. Collingwood believed that this was different than studying sciences. Tolkien, influenced by Collingwood, may have come to the same realization, and attempted to preserve history in his own writing.

On the other hand, Tolkien implemented the present day into his own writing. When Tolkien was writing The Hobbit, World War I was a recent memory. Fortunately, Tolkien contracted trench fever and was placed in a hospital, sheltered and protected from the war that he likely would have died in. You can see remnants of World War I in Tolkien’s writing with the large-scale wars, such as the Battle of the Five Armies, and the implementation of evil and suffering in his stories. Hannibal fought with elephants in the Battle of Zama: similarly, seeing the great Orcs at the Battle of the Five Armies fills Sam Gamgee with dread and delight, in a sort of revelation. Think of WWI’s overwhelming loss of life, baffling and awing normal Englishmen. Sam Gamgee is connected to the war because of men Tolkien encountered during the war. In battle, there would always be people to cheer others up when they were down, make them look on the positive side of things so that they could all maintain hope. Without Sam, a character fascinated by almost anything natural and free of vice, Frodo’s expedition would be a lot more lonely and full of low-spirits.

Tolkien also was similar to Frodo because of the sicknesses that Frodo would get along his journey, just like Tolkien had done during the war. Frodo’s experiences with the ring also haunt him even after returning to the Shire, similar to the psychological scars that the war inflicts. The Ringwraiths, to us, seem to be completely made up because there is nothing remotely similar in real world, but, throughout the World Wars, people who rode horses would wear gas-masks that would muffle their voices and protect them from the harmful fumes on the battlefield. The masks give them a mysterious and evil appearance, and played on everyone’s imagination.

Tolkien was brought into the investigation of Silvianius’s ring because of his expertise in language. His job was to study the tablet part of the ring, which contains the curse. Silvanius’s ring has the text ‘Senicaianus, may you live in God’ inscribed in Latin. (Seniciane vivas i(i)n de(o)). The One Ring has writing, which seen by firelight, reads: ‘One ring to rule them all, one ring to find them. One Ring to bring them all, and in the darkness bind them.’

“I propose to speak about fairy-stories, though I am aware that this is a rash adventure. Faërie is a perilous land, and in it are pitfalls for the unwary and dungeons for the overbold.” – J.R.R Tolkien

By reading other writer’s Faerie stories, Tolkien was able to learn what to do and what not to do. Tolkien not only shared his knowledge of Faerie stories through his books, he also taught it at the university level. In a lecture that became the book On Faerie Stories, he discusses and clears up ambiguities in the definition of the genre, and mentions a range of authors who have attempted to write in it, such as Andrew Lang, Lewis Carroll, Beatrix Potter, and many more. Faerie stories are difficult to write because of many specific requirements that must be met, to classify it within the genre. By pointing out other’s mistakes, and by classifying different attempts, he developed the genre further. Not many writers dare to journey along with Tolkien into this undeveloped realm because they fear making critical mistakes after seeing others attempt it. However, he mentions how the benefits of writing Faerie stories outweigh the difficulties. After creating many different characters and creatures, On Faerie Stories ironically teaches the reader and writer more about humans; it teaches you how to seize joy out of any situation, no matter how fantastic or terrible. Tolkien wanted to show that everything doesn’t have a happy ending; you have to learn to accept a defeat as something that can be built off of and learned from.

There are many misconceptions about Faerie stories, mainly because it contains the word ‘Fairy’. Not all the characters in faerie stories are small. It is believed by many people that a faerie story typically has a child who meets fairies, acting humorously and nice, too perfect to be believable. Tolkien dismisses these, and then defines the creatures who possess magical powers as they attempt to solve problems that men have created.

Little known inspirations behind Tolkien’s writing reveal how real-world components exist in his stories. Tolkien’s ulterior motives for the books, beyond creating a source of entertainment, consisted of aims far greater than just for his own ego; he developed the genre, making it easier for future writers to follow in his footsteps, he modeled how language creation is supposed to be done, and he preserved historically important events, or the memory of them, by creating his unique trilogy.

Bibliography:

Forest-Hill, Lynn; History Today “The Inspiration for Tolkien’s Ring“ Vol. 64, Issue 1, Jan 2014

Moore, Robert. “Sarehole.” Heart of England. Blogger, 4 Aug. 2011. Web.

Piittinen, Vesa. “Völuspá.” Tolkien Gateway. GNU Free Documentation License, 22 June 2015. Web.

Rhyes-Davies, John. “How Was The Lord of the Rings Influenced by World War One?” IWonder. BBC, n.d. Web.