NATHAN LUU

John Hodgman’s essay on Massachusetts was quite the pleasure to read.

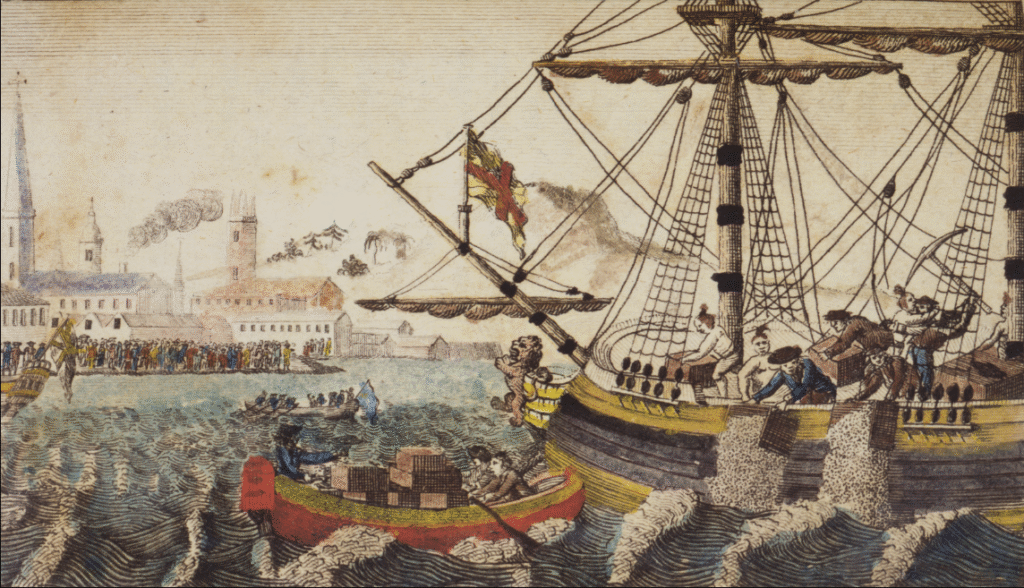

He writes about his home state, obviously showing a ton of passion and showing us a side of Massachusetts that not even myself knows too well. When people think of the state they either first go to all of the great colleges and schools in the Northeast, the state of sports, or about the history like the Boston Tea Party. Though in this essay, Hodgman hones in the western part of Massachusetts.

Like I said earlier, western Massachusetts is literally no man’s land – I couldn’t tell you more than three towns in the west. I just wracked my brains, and I came up lacking, so none, how’s that? I’ve always thought of it as a plot of land with trees all over and log cabins scattered all around. When Hodgman introduced the West he described “it was not near a town, and not near anything.” Adding to my point it shows just how empty and peaceful that part of the state can be. He also makes it sound a little lonely describing the long drives, silence, and the strange culture out there. It might just be me though, but when I drive out and about… I like to drive by myself in the quiet (not really quiet, music in the background of course), it’s just some time where I can think about the day or life in general with no one to hound me. But I’ve never seen “…cornfields and dairy farms and incongruous fields of shade tobacco for cigar wrappers”. Hodgeman calls it “Masstucky.” I believe that it could refer to the idea that some of Massachusetts isn’t really Massachusetts. It sort of reminds you of Kentucky where it’s less crowded and sort of the Wild West, nonetheless, the complete opposite of Eastern Mass. In contrast, the other side of Massachusetts is an absolute homewreck. If you have ever driven in Boston, you’d know how reckless people are in the car and on the roads. Every two seconds you see people jay walk across the road when the light turns green. Then all of a sudden you hear horns from every direction – your ears will be engulfed in car horns.

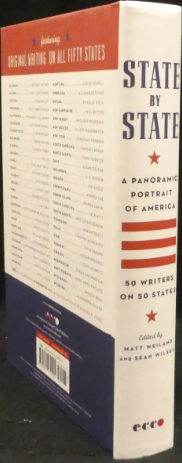

If you’re not from Massachusetts I bet you’ve made at least one or two stereotypical jokes about Boston – how they’re either the smartest state with all the elite education we have over here or about how dumb we are, like how we traverse the roads and what horrible drivers we are, or even our accents. Well I can assure you that, that’s all semi true. If you’re ever traversing Boston, you’ll come across a man in some Boston sports attire in his car screaming at the top of his lungs to get off the road in his Bostonian accent. Though, on the other side of the spectrum there are the high tier educated folks that go to Harvard or MIT, I can assure you that I haven’t come across a single student who has been to either school. There’s a small population of people that go to those schools and that small population doesn’t define our state (I mean if you insist, I’ll happily take the compliment of our state being called the smartest one out of fifty).