LEONA ZHOU

The Character Development of Gollum

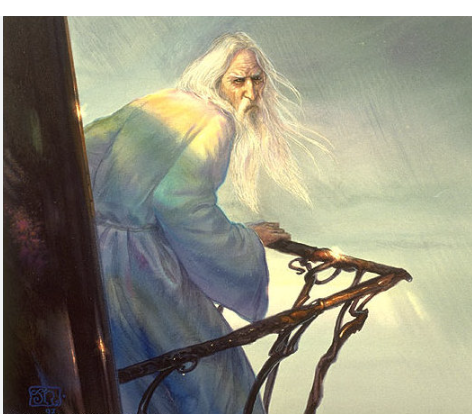

The first time we ever met Gollum is in The Hobbit. And even though he has been discussed in The Fellowship of the Ring, he was never really shown up. We finally get to meet him again in Book Four, Chapter One, where he has been tailing Frodo and Sam all along, and he was looking to get his “precious” Ring back. Now, how he has been discussed all along before we meet him made him sound like a vile, evil creature who has been devoured by the power of the Ring. But much to my surprise when I read Chapter One, his character has developed quite a bit. And yes, Gollum is a terrible creature, but Gollum is Gollum. He’s a whole different creature compared to Smeagol. Smeagol is a hobbit who found the Ring ages ago and was consumed by the power.

Essentially they are the same, but as we learn from Gollum’s monologue, he is talking to himself. Could the split be Gollum talking to Smeagol and vice versa? The way I see it, is that all the time with the Ring, it has created an evil, selfish creature inside of Smeagol, called Gollum.

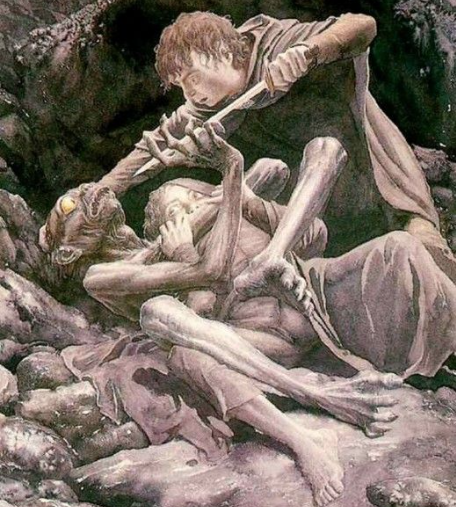

“‘Yess. Yess. No!’ shrieked Gollum. ‘Once, by accident it was, wasn’t it, precious? Yes, by accident. But we won’t go back, no, no!’ Then suddenly his voice and language changed, and he sobbed in his throat, and spoke not to them. ‘Leave me alone, gollum! You hurt me. O my poor hands, gollum! I, we, I don’t want to come back. I can’t find it. I am tired. I, we can’t find it, gollum, gollum, no, nowhere. They’re always awake. Dwarves, Men, and Elves with bright eyes. I can’t find it. Ach!’ He got up and clenched his long hand into a bony fleshless knot, shaking it towards the East. ‘We won’t!’ he cried. ‘Not for you.’ Then he collapsed again. ‘Gollum, gollum,’ he whimpered with his face to the ground. ‘Don’t look at us! Go away! Go to sleep!’”, (Tolkien, page 662). This quote is crucial to understand the psychology and the damage the Ring has done to Smeagol. The Ring has the power to change anyone; we have Bilbo as proof. But if it has been with someone like Smeagol for a very very long time, Smeagol is proof it will create a monster inside of you (Gollum) that will get stronger and stronger until you can no longer control it, until it bends your will. We learn that maybe Smeagol has grown in a way. He has grown extremely tired of being controlled by Gollum and the Ring, but since he’s powerless, he’s desperate and weak. But can he prove to be trustworthy? I’d say that’s hard to say after how he had once escaped one of the most strongly guarded prisons. Around the end of Chapter One, we can see that Frodo makes Smeagol or Gollum promise that he will lead them to Mordor, with the threat that if he doesn’t they will use the Elves rope to bind him, causing him torturous pain. At the end of the Chapter, we get a closer look at Smeagol’s personality, or at least how he is around Frodo and Sam. “From that moment a change, which lasted for some time, came over to him. He spoke with less hissing and whining, and he spoke to his companions direct, not to his precious self. He would cringe and flinch, if they stepped near him or made any sudden movement, and he avoided the touch of their elven-cloaks; but he was friendly, and indeed pitifully anxious to please”, (Tolkien, page 664). There is a humongous effect the Ring had on Smeagol after such a long time. But yet, Frodo proves there is a power that can weaken the monster the Ring had created inside of Smeagol: kindness.