Spoiler Alert for “William and Mary” by Roald Dahl. Do not read unless you have read the story.

The story “William and Mary” by Roald Dahl is an interesting tale of a man dying and undergoing a science experiment that flipped the science world on its head. The story starts with William’s wife Mary taking a letter from her solicitor from her late husband. Mary was never extremely fond of her husband. He was restricting her as he never allowed her to smoke, and she never liked the way he looked at her. She described his gaze as “ice blue, cold, small, and rather close together, with two deep vertical lines of disapproval dividing them” (Dahl, 3). Although she may have loved him earlier in his life when they were first married, it has become clear that their bond had been weakened. She scolded him in her mind, saying that he was always formal, and never lightened up. This clearly made her frustrated with him, although his job was to be formal as a professor. She opens the letter after some contemplation, and begins to read it.

The letter describes the confrontation between Dr. Landy, a man who seems a bit too excited talking to someone who’s on their deathbed and the recently deceased. However, this is made up for by what he proposes to William. Landy first describes a gruesome experiment involving the severed head of a dog. This experiment suggests that the brain can survive outside the body, past death, with only an artificial heart pumping oxygen and blood through it. Landy, inspired by this idea, invents a way to keep a person’s brain alive without the rest of its body. He selects William Pearl as his subject, and when William dies, his eye and his brain are separated from his body and kept alive. Of course, he couldn’t hear or talk, but he could think and watch once he regained consciousness. This was Landy’s goal, now achieved.

After reading the letter, Mary makes a beeline to Landy, who had already finished the experiment and now has William’s brain out and conscious and his eye floating in a basin. It’s rather gruesome sounding, and I don’t want to think about it more than I half to in the name of science. Anyway, Mary meets this form of William, and is enchanted by how weak and helpless her once stern husband is. She compares him to a pet, something that she must take care of. She sees her husband in a new light, perhaps seeing him once again as the loving man she married. She asked Landy if she could take him home, to which she got a definite no. But she is adamant about her take on the situation, and insists on having him back home.

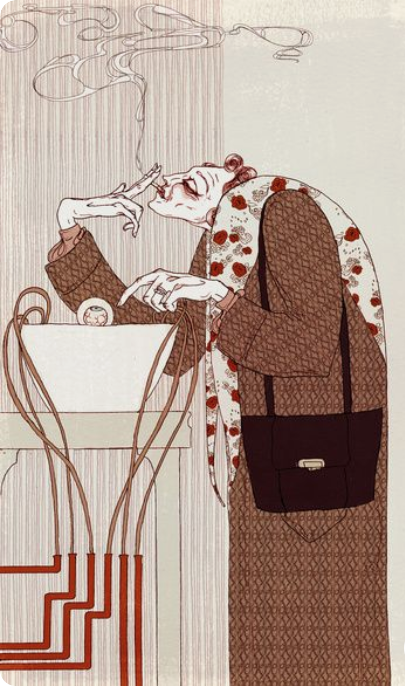

She starts to really care about her husband when she first arrives at the facility where William is. She insists on putting the headline in the Times because William preferred the Times. She also insisted on calling William him rather than it. Can a person still be called by pronouns denoting people in the state that he was in? That could be up for discussion. She also said firmly to Landy after telling her that he wasn’t looking so good: “I didn’t marry him for his looks, Doctor” (Dahl, 20). The text also states that she seemed sullen, weathered, and overall tired-looking. She was all chipped and drained away through years of being with a man that didn’t make her very happy. When she stares in his eye, she finds a feeling of kindness and calm that she never saw in him when he was fully living. She realizes that this is the William she had been missing all of her life. She states that “I believe that I could live very comfortably with this kind of a William. I could cope with this one.” She likes this William much better.

But she starts to get feelings of power, the feeling that she was finally above him, she could do whatever she wanted and he couldn’t stop her. He couldn’t stare at her and say that he disapproved of what she did. She even called him “the great disapprover”. In fact, although he said in the letter not to buy a new television set (which was likely something that he told her while he was fully alive), she bought it anyway and put it up on his desk. She was clearly feeling rather rebellious when she did so. She smokes right up in his, er, eye, which was something he very much disapproved of. Mary felt that she was now in control of her life and that no one could really stop her. She was going to live out the rest of her days the way she wanted.

Overall, this was a fascinating story, filled with facts about the brain that we never knew we needed, tidbits and mini stories within the main plot, and different perspectives and views within the limited vision of one character. This had that classic Dahl feeling to it, the feeling that you were both against and rooting for the protagonist. In this case, we see that Mary had been slightly mistreated by her husband but turns almost disrespectful and rebellious to him when he died. It was a pretty gruesome tale, and was not meant to be read by the faint of heart, but was informative about speculative science, and sheds light on a subject that was likely not pondered by many. I can see members of a Christian society getting rather angry and worked up at this tale; after all, it does involve someone transcending death, claiming that there was no heaven nor hell, as well as other more atheistic subjects. It was a very interesting tale that I very much enjoyed reading, and I hope to continue to find other stories that interest me as much as this one did.