The Methods of Silence of Seneca the Younger and William Hazlitt

The Methods of Silence of Seneca the Younger and William Hazlitt

Phillip Lopate, born on November 16, 1943, in Brooklyn, is a film critic, poet, writer, and essayist; he graduated from Columbia University with a BA and Union Institute & University with his doctorate degree in 1979. Over his career, Lopate has written a large collection of works, spanning eight collections of personal essays, three novels, a memoir, a collection of his movie criticism, and more. Additionally, he has edited The Art of the Personal Essay, an anthology of personal essays. The so-called fountainhead of the personal essay, Michel de Montaigne, has an essay featured: “Of Books” is included in this collection; James Baldwin’s “Notes of a Native Son”, covering the harsh reality of racism in 1940s New York City; Virginia Woolf’s “Street Haunting”, a rambling, both physical and verbal, through London streets for a pencil; and E. B. White’s “Once More to the Lake”, a father’s projection of himself onto his son.

The personal essay is casual – more similar to a letter than the traditional persuasive or critical essay many students are familiar with, and may surprise the reader with its variety of inward-looking components. As the name suggests, the personal essay is written from the author’s experiences, sometimes addressing the reader, or by entering a dialogue with oneself. Woolf’s Street Haunting cajoles the reader to join her on her walk, where she simply talks to herself as she goes along: she brings the reader along with her on her physical and intellectual journey to buy a pencil.

Personal essayists search to find the limits of their knowledge; they, like other great writers, “are adept at interrogating their ignorance. Just as often as they tell us what they know, they ask at the beginning of an exploration of a problem what it is they don’t know – and why” (xxvii). Lopate classifies this interrogation as the “contraction and expansion of self”. Lopate loves contradictions, and celebrates that the most successful writers are able to both expand outward from their limited view, and to focus in on the details of their frailty, to reveal something universal. However, the greatest complication an essayist will face while writing a personal essay is to appear self-centered. According to Lopate, “the trick is to realize that one is not important, except insofar as one’s example can serve to elucidate a more widespread human trait” (xxxii). Lopate argues that the subject of the personal essay, the author, should utilize their own experience to help the readers understand themselves. For example, when I read Woolf’s Street Haunting, it reminded me of my own partially aimless walks outside for the supposed purpose of taking pictures. Woolf strolls the London streets, allegedly for a pencil, but really to air herself out, to cleanse her writer’s mind, to ruminate and to excavate the characters and scenes she sees unfolding around her.

Contrary to Woolf’s diving into the personal lives of others, I take my walks to escape the excess of human interaction. For Woolf, the busy streets provide her relief from the solitude of her study, where the task of her writing impedes her interaction with her fellow Londoners. She seeks the noise, the clamor, and the business. Others, however, myself included, take walks to clear the mind, to search for stillness. You may ask why writers need such silence, having already isolated themselves within their studies, and perhaps you are right. But their studies are crammed with books, and while needing isolation to work, everyone needs space, and movement to clear the mind. Similarly, I spend a large amount of my time studying at home, and I do talk to friends online. But I find my walks crucial to my productivity. “Why do you go on your walks?” you may ask. I go to escape my work and to clear my mind, freeing it from obligations.

Personal essayists choose topics that contrast themselves against society, engaging and providing new perspectives; in Roland Barthes’s Leaving the Movie Theater, Barthes “goes to movies as a response to idleness” and, when he leaves, “he walks in silence”. He does not speak, coming out of the hypnosis of the experience, unlike those around him. This attitude of the writer, which seems to be antagonistic, is in fact the very reason we read: his view is different: it is a contraction where expansion is expected, some new angle. Personal essays are quite often unusual and provocative. “Behind these contrarieties is a fear of staleness and cliché, or, to put the matter more positively, a compulsion toward fresh expression” (xxx). Asthma, written by Seneca, puts asthma in a novel light. He describes asthma as being forever “at your last gasp” (8), ranking it as the lowest of all diseases.

As I prepare for the college admissions process, I have been attending informational sessions on the college application process, and, whenever the essay is mentioned, the first point the speaker makes is that the essay should be personal. The essay is an outlet for a seventeen year old to be a seventeen year old; it is not an outlet for generalized hopes of world peace, nor is it a means to describe the lives of impoverished children. The admissions officers want the honest high school student; one of the best methods of conveying honesty is through confession. One successful essay begins with a confession of a crime: “I had never broken into a car before”. The essay transitions to a short narrative of the event, and then to a discussion of coping with peer pressure. Despite the initially revealing nature of such a confession, the student connects with their audience through their mistakes. The personal essayist must bare their “naked soul… to awaken the sympathy of the reader, who is apt to forgive the essayist’s self-absorption” (xxvi). This baring of the soul, to appear less self-absorbed, is achieved through confession; the reader is always confronted with this edge. How is the essayist so effective, having shared their flaws? The reader sympathizes and understands.

As I read William Hazlitt and Seneca’s essays, “On Going a Journey” and “On Noise”, respectively, I felt connected to the authors in their search for solitude of mind, and I was surprised to see how such an esoteric subject could be treated so differently, expressing the personalities of the writers. As solitude is an important part of my daily life, I felt especially drawn to think further about these two great essayists.

.jpg)

William Hazlitt was an 18th century English essayist, critic, painter, and philosopher. Initially, Hazlitt attended the New College, to prepare for a ministerial career, in Hackney, a working class section of London, but he lost his faith and left the school. He stayed at home, studying great philosophers, and portrait painting for an income. His painting career was very successful, through which he met poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who greatly inspired Hazlitt. Coleridge, a preacher who had not yet accrued any fame as a poet, encouraged Hazlitt to develop his writing skills, which he applied to his self-published philosophical essay, An Essay on the Principles of Human Action: Being an Argument in Favour of the Natural Disinterestedness of the Human Mind, and he turned to journalism. He wrote for both the Examiner and the Edinburgh Review, the former a national weekly publication and the latter a prominent periodical among the Whigs, contributing a broad variety of articles, most of which were critiques. Characters of Shakespeare’s Plays became a popular essay collection among the public. Unable to support his wife and son, he got a divorce and spent a few years between London and the countryside. During this period, he wrote On Going a Journey. The essay discusses going on a journey into the English countryside, “one of the pleasantest things in the world” (181) to Hazlitt, but he appends: “I like to go by myself” (181).

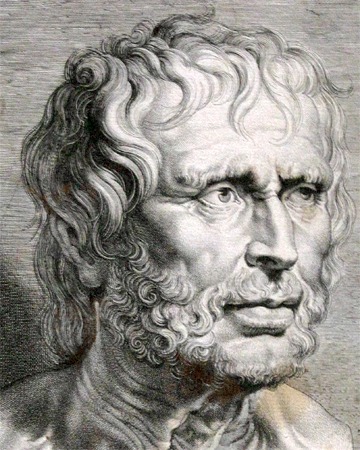

Lucius Annaeus Seneca, (4 BC – AD 65) also known as Seneca the Younger or simply Seneca, was a Roman philosopher whose formal works were “tragedies… dialogues, and orations” (3). He was in the Stoic tradition started by Zeno of Citium, three hundred years before his birth: the Stoics believed that destructive emotions occurred through conflict between human thought and nature, and therefore emphasized maintaining a will that was in harmony with nature. His early career was unstable: he just barely escaped execution under Caligula, who envied Seneca’s gift for oratory, and was exiled by Claudius’s first wife. Luckily, Claudius remarried and Seneca served as the tutor, and later advisor, of his son, Nero. After the murder of Agrippina, Nero’s mother, by Nero’s request and the death of his fellow advisor, Seneca retired in 62 AD and later moved to the countryside.  During his career under Nero, Seneca had amassed a large amount of wealth, which was seen by some as antithetical to his Stoic philosophy. However, Seneca redeemed his Stoic qualities in death; Seneca was ordered to commit suicide by Nero, having been allegedly involved in Piso’s conspiracy to kill Nero. His death was slow and painful – despite ingesting poison and lying in a tub of warm water, the blood flowed slowly from his slit veins. During his lifetime, Seneca wrote nine tragedies and one satire. His dramatic works, written prior to his retirement, heavily employed rhetorical strategies and were written without concerns for stage requirements. In addition to his formal work, Seneca’s personal essays are “in disguise, [they are] ‘moral letters,’ written during Seneca’s [retirement], [and] were probably intended from the start for publication rather than for their ostensible recipient, a civil servant named Lucilius” (4). The letters were written over Seneca’s retirement – On Noise was written just prior to moving to the countryside, while he was attempting to apply Stoic values to city life.

During his career under Nero, Seneca had amassed a large amount of wealth, which was seen by some as antithetical to his Stoic philosophy. However, Seneca redeemed his Stoic qualities in death; Seneca was ordered to commit suicide by Nero, having been allegedly involved in Piso’s conspiracy to kill Nero. His death was slow and painful – despite ingesting poison and lying in a tub of warm water, the blood flowed slowly from his slit veins. During his lifetime, Seneca wrote nine tragedies and one satire. His dramatic works, written prior to his retirement, heavily employed rhetorical strategies and were written without concerns for stage requirements. In addition to his formal work, Seneca’s personal essays are “in disguise, [they are] ‘moral letters,’ written during Seneca’s [retirement], [and] were probably intended from the start for publication rather than for their ostensible recipient, a civil servant named Lucilius” (4). The letters were written over Seneca’s retirement – On Noise was written just prior to moving to the countryside, while he was attempting to apply Stoic values to city life.

You can achieve silence through solitude, but solitude is not necessary for silence. Hazlitt searches for solitude, choosing to be alone to find calmness in his mind and freedom in his actions. He sees no point in talking while walking – only to “vary the same stale topics over again” (181). Hazlitt is not the type who goes to Brighton Beach with a group of friends, with a picnic basket, not someone who would readily join an excursion to a cabin, with a group of men. Nature provides him with sufficient company. The freedom from others is “the soul of a journey… [the] liberty… to think, feel, do, just as one pleases” (181). He is free to laugh, run, leap, and sing for joy, far away from puns, alliterations, and other figurative language, in an “undisturbed silence of the heart which alone is perfect eloquence” (182). Alone, Hazlitt can ponder his own past being, reveling in the “sunken wrack and sumless treasures” (182) that resurface, bursting like bubbles into the view of his inward-looking eye. He feels like himself again, free from the writerly duties that he employs every day (“No one likes puns, alliterations, antitheses, argument, and analysis better than I do”) and he has no obligation to end his reverie hastily – there is no worry of neglecting others, of appearing poorly mannered to his friends – as would be necessary if he strayed momentarily from a group: he is truly alone, separated from others indefinitely, with no requirement to return, allowing him to indulge himself with his musings, to return to his past self and enjoy the feeling of freedom without becoming a bad companion. For Hazlitt and like-minded people, therefore, is best to search for silence alone, on solitary walks with no particular goal, in the countryside or on deserted streets, with nothing more than the present.

Seneca, too, is inwardly undisturbed, despite living above a Roman bathhouse. He lives above the din of discordant voices that sing merrily from a bath, the clamor of cattle as they are herded through the streets to the market, the bubbling laughter and outraged shouts of street urchins and vendors in pursuit. Seneca, however, requires no solitude to achieve his silence; his silence emerges from a focus of mind, a tuning out of the myriad sounds beneath him: “I force my mind to become self-absorbed and not let outside things distract it” (6). Voices are, of all sounds, the most distracting, for they create coherent messages that grab one’s attention. But even without voices, in perfect stillness, there is no true silence until the mind is calm. To be at peace is to have mental silence. Literal silence only provides time to think, and, for instance, when one’s emotions are in turmoil, silence can amplify them to deafening levels. By calming one’s emotions, silence is achieved. But is silence, or quiescence, the goal? Or is silence the requirement for further inquiry? If Hazlitt is so intent on being alone, away even from a companion, is it so he can enjoy quiet? “When I am in the country I wish to vegetate like the country” (181).

“People who are really busy never have enough time to become skittish” (6), writes Seneca, insinuating that if the mind is unshaped, uncontrolled, and unbridled, the individual is obviously lazy. It takes work to focus the mind when a brawl begins outside your window. Skittishness of mind may be more applicable to Hazlitt, as he can’t block out his friends’ voices, but it seems that both men honor the focus required to still the mind, knowing, as they both do, that a free mind is the treasure of humanity. What then is required to ignore the surrounding commotion, to concentrate, to achieve a state lacking in turmoil, unresponsive to external noise? Mental focus. One can search for silence within, focus on that sole task, but any distraction, of which there may be many, can disrupt a wandering mind. And Seneca demonstrates that being responsible enough to focus the mind is a requirement and a duty.

To achieve their silence, each author pursues their own path. Hazlitt frees his mind of distractions by escaping attachments, by journeying alone, distanced from others. Isolated, Hazlitt is able to indulge his mind upon himself; in this silence he can focus on his own issues rather than those around him. Seneca practices a stoic approach to obtain his silence: he disengages his mind from external occurrences, removing his thoughts from unrelated events, utilizing rational thought to arrive at mental silence. Hazlitt demonstrates an untrained mind, as he is only able to flourish in the perfect silence of isolation; Seneca, through his essay, purports to be above external circumstances, and proves it to a degree with his timeless descriptions of the bathhouse and the din from the street, but neither are able to fully express the conditions for peace of mind, as these perfect conditions never can be met. The mind is a difficult entity to train, and neither writer has completely mastered it, though they try various approaches.

Despite their differences in methods, both would agree that solitude enables silence. The two differing methods of obtaining silence rely on the same principle – the removal of self from distractions. In the last paragraph of his letter, Seneca caves in upon his stoic philosophy and admits that he will soon move into the countryside, away from the din of the bathhouse. Although his mental fortitude is strong, the physical separation from distractions is the more direct method to silence, independent of a strong will, and Seneca joins Hazlitt in solitude. Both writers attempt to uncover the methods for perfect silence, which neither has achieved, by examining their own experiences, having only had success under certain conditions. Seneca scrutinizes the efficacy of his Stoic principles in achieving silence, but concedes the advantage of solitude. He reveals his imperfect understanding. “One may speak of a vertical dimension in the form: if the essayist can delve further underneath, until we feel the topic has been handled as honestly, as fairly as possible… (xxv)”, then the essay is highly effective. Seneca’s goal is lofty: he is a philosopher. What Hazlitt and Seneca strive for is a clear mind with which to mull upon the cause for their clear mind; they share their process in these excellent personal essays, hoping to achieve a better definition of the conditions for silence of mind.