The Time When Korea Owned China

Many times, it seems that ancient histories of countries are displayed much more than other countries, just because they are looked at with such superiority. But don’t sleep on Korea because they’re right up there and deserve to share the spotlight. China is often looked at as a major power in many history books, as it is massive and in the heart of Asia. With Korea being a small little peninsula, looking over at a country that is almost 100 times bigger than itself, it is small but mighty when it comes to its history.

Many major world powers have one thing in common, which is having a benefit from physical features that may form barriers or provide an advantage to that region. Although Korea seems petite, it has a massive advantage being a peninsula, having three sides surrounded by water. Additionally, another advantage is that a great part of the country is mountainous.

Nations are formed by borders, language, and common history – what connects a people together and unifies them is an origin story that binds them to their roots.

Many modern nations’ origin stories consist of the creation of the nation itself, but with countries as old as China and Korea, their stories correspond with the creation of the world.

To really get a feel on what was at stake in this dramatic and intense series of invasions against Korea, we need to get a sense of the identities that these nations display, their beliefs, motives, and roots. All of these things were very different between these two rivals back then, so let’s take a look at each individual region’s basics and ancient identities.

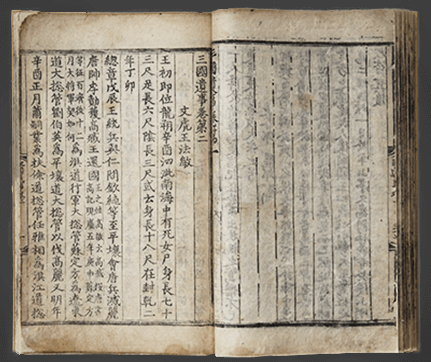

Samguk Sagi, known as the oldest living piece of writing in Korean history, was based on the history of the Three Kingdoms. It was created by Kim Pu-sik (1075-1151).

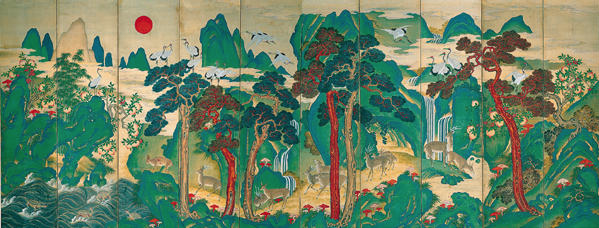

As mentioned, you will find that the ancient Korean origin narrative is not only about the formation of Korea, but also the creation of the world. The ancient Korean formation legend dates all the way back to 2333 BC, when Hwan-in, the heavenly king, had a son whose name was Hwan-ung. Hwan-ung had strong ambitions to descend from heaven and live in the human world. Hwan-in gave Hwan-ung three heavenly treasures and commanded him to rule over his people in the human world.

Hwan-ung descended from heaven and onto the T’aebaek Mountain, along with three thousand of his followers, settling there. He called the mountain Sin-si, meaning City of God, and led his ministries of wind, rain, and clouds, the originating weather patterns of the world. He also taught his people more than 360 arts, consisting of agriculture, medicine, moral principles, and codes of law. It is not clear how long they settled there, but at a certain point, two half animal, half humans came into the picture.

Nearby, in a cave, there was a she-bear and a tigress. They prayed to Hwan-ung to be blessed as human beings. In response, Hwan-ung gave them twenty pieces of garlic, and said that if they ate them and didn’t see sunlight for one hundred days, they would become human beings. The she-bear and tigress took this offer and went back into their cave. Just 21 days later, the she-bear became a woman early, because she had obeyed his order, unlike the tigress, who had disobeyed the order by emerging from the cave prematurely.

The new woman (no longer bearish) realized that she couldn’t find a husband, so she prayed to Hwan-ung to bear her a son. Hwan-ung heard her prayers, and visited her, married her, and she bore him a son named Tangun. Tangun grew up and set up a royal residence in Pyongyang, the nation’s capital, and created his kingdom. He later moved to nearby Asdal, modern day North Korean province, Hwanghae, and ruled for 1,500 years there. He became the mountain god at the young age of 1,908. Just like in the Bible, the early human beings seemed to live a very long time, though Tangun almost doubles the age of the oldest-known human being from the Old Testament, Methusaleh, aged 969.

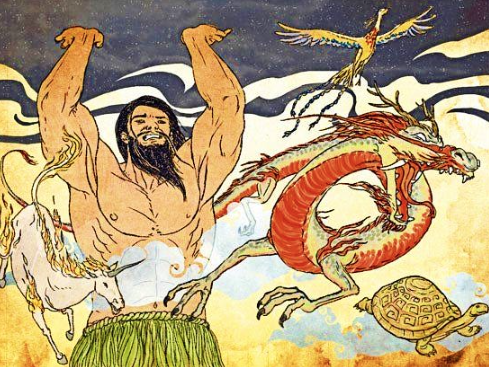

Like Korea, and perhaps even older, China’s origin myth corresponds with its national identity. Across the Yellow Sea, the ancient Pangu Chinese myth was written around 220-265 AD, by Xu Zheng, though it was told long before that oral tradition.

Like Hwan-in, there is an originating king, or creator god: Pangu. Pangu was inside a huge egg containing chaos, the mixtures of yin and yang, male and female, aggressive and passive, cold and hot, dark and light, and wet and dry. Within this egg full of chaos, Pangu broke from the egg as a giant, and unleashed the chaos.

Yin became heaven, and Yang became earth. Pangu stood in the middle of the opposites, his head touching the sky and his feet planted on the earth. Heaven and Earth began to grow rapidly, 10 feet per day, and so did Pangu. After 18,000 years, Pangu stood between them 30,000 miles high, so they would never join again. When Pangu died, his skull became the top of the sky, his breath the wind and clouds. His voice became thunder. One eye became the Sun, and the other the Moon. His body and limbs became five big mountains, and his blood the water. His veins became roads, and his muscles the fertile land. His hair and beard became the stars, and his skin the flowers and trees. His sweat flowed like rain and sweet dew. Even the fleas and lice on his body became the ancestors of humanity.

Some say that Pangu didn’t die and became human, and a half dragon goddess named Numu created humans out of clay. Numu found forming figures out of clay too time consuming, so she dropped a string across the mud and made a whole bunch of them, this becoming the reason behind social stratification.

The two origin myths have a direct connection with each countries’ motives. China represents the god Pangu, and that he is the almighty power and rules over the earth. He is displayed literally as the earth itself, signifying that China is a force and a power of the earth. Korea, on the other hand, also displays the creation of the world, but is specific to where the small group of people, the Hwan-ung, are located in Pyongyang, developing their own culture – leaving the rest of the world a mystery. These two motives may show the reason for how the outcome of the war came to be, and why one side unanimously succeeded.

Let’s fast forward several thousand years to the 6th century A.D., when China has just entered a new era of rulers. China was united by the Sui Dynasty (approximation of date 589 AD) under Yang Jian (Emperor Wendi), after defeating the Chen Dynasty. This unification made China see itself as superior to other countries in Asia, and other countries yielded themselves to them.

Emperor Wendi, aka, Yang Jian, was the founder of the Sui Dynasty. Emperor Wendi, unlike many other emperors at the time, used his power for his people rather than himself. He was a very suitable emperor for China at the time, being a very worthy ruler. Emperor Wendi was overall a very good emperor for the time, and his reign was known to be prosperous. He was known as a Confucian Perfect Gentleman. A Confucian Perfect Gentleman is made up of five characteristics: humility, sincerity, graciousness, magnanimity, and diligence. After he was settled and had the throne, he attacked with 500,000 troops to invade the Chen Dynasty in the south of his nation, eventually uniting all of China under the Sui Dynasty.

During Wendi’s reign, he distributed land very fairly, having a system that distributed land based on the size of families. Additionally, taxes on farmers and merchants were less chaotic than his predecessor, Yuchi Jiong, resulting in a very productive agriculture period. Emperor Wendi acted for not only himself, like many other emperors would, but for the people’s own good. However, all this success was later to be destroyed by his son, who murdered him, and couldn’t keep Wendi’s greatness going. Emperor Wendi was already on bad terms with his son, for he stripped him from his title after he was caught raping one of Wendi’s concubines. The son, after doing this terrible crime, successfully kills Wendi as a coverup. Could you imagine strangling your father to avoid the punishment of a crime you committed?

Before Korea was its own united country, it was split into three regions: Baekje, Silla, and Goguryeo. These regions were known as the Three Kingdoms. Goguryeo dated back all the way to 37 BC. Silla was established in 57 BC, and Baejke in 18 BC. Can you hear the word Korea in any of these three names? Go ahead and try it out for yourself. Any luck?

All the tension between Goguryeo and the Sui Dynasty started when Goguryeo wouldn’t surrender themselves to the Sui. Goguryeo thought that they should have an equal relationship with the Sui. Because of this, Sui didn’t like the fact that Goguryeo challenged them.

Goguryeo put together small raids into Sui’s border, so Wendi sent papers telling Goguryeo to stop any military alliance with the Turks (ancient Eastern Turk Khanate, not modern day Turkey), demanding they acknowledge the Sui Dynasty as superior. In response to this, Goguryeo launched a preemptive invasion against the Chinese in 597.

So now let’s jump to the conflict that between 598-612 AD created the boundaries of modern day Korea: the Sui/Goguryeo War.

The first real invasion happened in 598 BC, following the 597 attack.

***

The year was 597 and Hu Min was helping build the Fang Ships for the upcoming invasion of Goguryeo. The sun was blazing right on top of his neck, as he was finishing up the oars of the FANG ship. This massive monstrosity of a ship took hundreds of men to complete, and several months to build. As they were right next to the beautiful Three Gorges of the Yangtze River, Hu Min wanted so badly to jump in the glossy, clean water, and feel the cool lemon-like water. But he and everyone else knew that Emperor Wendi and Admiral Zhou needed the ship done as soon as possible before the invasion. As the ship was almost done, Hu Min took a step back to look at what was at hand; with six 50 foot-tall rods, and five layers of perfection, the ships were to be used in a few months from now, and Hu Min thought Goguryeo had already lost.

Hu Min had just turned 18, but had been working hard since he was little. For what seemed like countless months, he was ordered to work on these huge, intricate ships. As he stood looking at the Fang Ship, he couldn’t help but feel waves of pride. From the wooden castle walls that acted as an upper tier of crenellation, designed for archers and crossbowmen, to the 50 foot striking rods, designed to demolish any enemy within distance, from the five layers of complex designing, meant for crushing ships abeam, to the cypress booms that was the center of destruction of the ship, this FANG knew no rivals.

Once the Goguryeo army had spotted this monstrosity containing 6 striking rods that could be dropped at any time to crumple an enemy ship, and several floors with hundreds of soldiers, they would flee at the sight.

“Hu Min, get back to work!” yelled an officer. “Do you see anyone else lacking? People like you are going to get us killed!”

“Yessir!”

“We’re almost done, and we need this done fast, to show Emperor Wendi how skilled and hardworking you all are. We need to make sure he sees the five layers of absolute glory, 40 oars put together with hard work to sail over any wave in any weather, sky-high striking rods designed to give goosebumps to any opponent, and finally the sheer countless number of these FANGs will ultimately bring glory to China. So make sure you’re not the reason that doesn’t happen!”

Because of his father, Hu Min from a very young age had been involved with the military. He served as a cabin boy when the Sui invaded the Chen Dynasty 9 years prior, running errands and scrambling around for the captain. He was young and couldn’t fully comprehend the level of intensity that was at hand, but remembered a time when he saw the mass destruction the striking rods had cost. The striking rods were 16.7 meters high, and had a stone boulder on top. In battle, the boulder would be lifted up to the top, and then would be released on top of an enemy ship. The rod could be used repeatedly. This was the main weapon they had used to win the naval battle in many previous conflicts. Hu Min saw often that the boulder would come crashing down onto the enemy ship, and go straight through like butter, either decimating the ship, or making it unusable.

It was a clear dark night, and Wen of Sui was laying on his triple king-size bed. He was thinking about Goguryeo, and how they just wouldn’t seem to acknowledge the Sui Dynasty as the superior power in all of Asia. On top of this, they had launched a preemptive invasion just last year. While laying in bed, Wendi came up with a plan that he thought would be both unpredictable, and unstoppable, forcefully bringing Goguryeo to their knees. The next day, Wendi ordered a meeting with Admiral Zhou Luohou, the Chinese naval leader, general, and administrator. Although he was old, with a fairly long beard, and a frail face and body, he was one of Emperor Wendi’s most reliable assets. Yang Liang, who had a round, chubby face, and a bulky body, was the prince under Emperor Wendi, and led the land pursuit in the invasion, was present with Luohou, to go over what he’d cooked up the night before. His plan was to send 300,000 troops to Goguryeo! But little did Wen of Sui know that his plan wouldn’t be as nasty as he had intended it to be.

Jin Seoung was a man in his 40s who had dedicated most of his life to the Goguryeo naval army, on the coast near Pyongyang. He had joined the navy when he was 18 and had been in the naval section ever since as a captain. When the news of an invasion of the Sui Dynasty came to his attention, he was forced to leave his wife and two kids, ages 8 and 6, at home, and proceed to battle. Jin Seoung didn’t know what to expect, for he was told that his job was to be on the lookout for Sui ships coming at Goguryeo. When he embarked on the Yellow Sea, instant storms and cold weather hit him and his fellow sailors. But this was part of his long military training – withstanding any sort of weather when at sea, and still fighting the enemy. He and other vessels waited out at sea, waiting for any sign of Sui ships, praying for safety.

After three weeks on patrol, the weather got even more worse and dangerous. They were about a mile out at sea, and Jin Seoung was getting pretty exasperated, thinking of his family. Each storm got more violent, with more wind and less visibility. Each passing moment felt like an hour, and Seoung’s hands became frozen in his pockets – his breath was freezing in the air. Despite the many layers of clothing, the wind made it hard to even open one’s eyes, and even then, there wasn’t much to see. Despite all this, Seoung knew he needed to stay on his assignment and lead Goguryeo to success. One blistering morning, he thought back to his military training and the finest moments he’d witnessed in battle, and called on all the soldiers on his ship and told them that Korean liberty was worth the sacrifice of a few weeks of discomfort, and that the people on the ship would go down as heroes if they could successfully stop the Sui invasion.

A few days prior, Emperor Wendi had heard the news that Yang Liang’s land pursuit had been stopped short due to weather and a surprising number of Goguryeo forces.

Emperor Wen had sat on his throne, his hand stroking his beard, contemplating the next move. After a few hours, he decided that a second part of the invasion was necessary and would surely catch Goguryeo off guard via FANG ships and a naval attack. Admiral Zhou was one of his best assets in winning this war with Goguryeo, and this was the time to decimate Goguryeo. Goguryeo had barely dodged the first swing – the left uppercut was on their blind side.

But as Admiral Zhou was walking out of Emperor Wen’s majestic palace, he found it hard to fathom what had just been asked of him. He was now expected to create a flotilla and pick up for the fallen soldiers, to lead a new total of 300,000 soldiers and sailors in a combined invasion.

A few days later, the naval fleet, under Admiral Zhou’s command, was on their way to Goguryeo. But because Admiral Zhou was in such a rush to get his naval army in action, he hadn’t anticipated the poor weather at hand. He had taken note that the soldiers had been stopped because of the weather, but didn’t think much of it. Smoke and sound signals were most likely the form of communication between these ships, but because of the low visibility, communication was limited, for the fog dampened sound and obviously was impenetrable, being smoky itself. When Zhou combined his forces with the soldiers, it still wasn’t looking auspicious. Zhou was losing ships fast due to the weather, their top-heavy construction becoming a vulnerability not yet tested; that and constant Goguryeo ambushes were taking their toll. FANG after FANG, those towering battle axes of the sea, were sinking! The ultimate hope of the mission was that the ships would reach Goguryeo’s shoreline, and the soldiers would proceed their ambush, but one, the soldiers were already in poor condition with illness and fatigue, and two, the ships weren’t getting there in the first place. The numbers dwindled fast. A normal day for Zhou was this: lead his naval fleet with a valiant attempt at communication, but at night he’d resort to sitting on the deck, listening to the pouring rain, wind, and thunder, praying that he wouldn’t have to deal with another Goguryeo ship ambush.

Once they finally reached the shores of Goguryeo, they were ambushed by a small series of ships that caught them off guard. With no visibility, the Sui had no idea what had hit them, and more ships were demolished. But now at the border of their enemy, they knew there was no turning back. Zhou’s navy was exhausted and worn out.

A few days later, Admiral Zhou encountered the bulk of the Goguryeo naval fleet. There were only a few hundred ships, so Admiral Zhou thought this would be like snacking on a piece of mooncake. They clashed with the first layer of Goguryeo ships, and were surprised at how powerful they were. Despite this, Admiral Zhou still thought this would be an easy victory with how much of an advantage they still had in numbers. After they blasted through a few layers of the Goguryeo fleet, Admiral Zhou became a little confused, for Goguryeo ships just kept coming at them, seemingly in an infinite number of layers. With Zhou losing ships rapidly, he became a little worried as to how many ships Goguryeo actually had. All of a sudden, 20,000 of Goguryeo’s highest quality ships instantaneously surrounded his fleet, absolutely demolishing the remaining ships. Zhou had just a few milliseconds to process this, before he saw his surrounding ships split in half, bloodied sailors drowning.

Jin Seoung celebrated the victory with yells and cheers with pouring rain and wind. As soon as the Goguryeo ships retreated, the weather became a second thought. Jin Seoung had successfully led his group of ships to victory. His strategic plan had panned out flawlessly.

But Admiral Zhou was a tough man, for throughout his childhood, he had always liked to play military games with other daring kids in his neighborhood and as a young warrior, he’d distinguished himself from many in battles, receiving the title of Kaiyuan General. During a battle in 573, an arrow struck him in the eye. He continued to fight, and when his general was surrounded by opposing troops, Zhou and his subordinates bravely fought off and routed the enemy. Throughout his life, Zhou had distinguished himself by saving many important people. He had found much success in fighting, but this invasion was his biggest test. But even the strongest fail, and in this case, he fell short. With all the factors stacked against him, he couldn’t prevail. He was deFANGED.

The second invasion occurred in 612:

The year is 611, and it is Hu Min’s 31st birthday. He is hoping to relax and stay in to spend time with his family, but he is receiving an order from the Sui military. With little details on what is going on, Hu Min is rushing to the army camp, and receives his order of constructing a canal that connects the north and south part of China. The canal is almost done, but he’s needed as backup support from the many workers who have died during the construction. With little idea about the details of his task, Hu Min has no idea of the danger in constructing this massive canal.

“What’s going on? Hello? What’s this canal about?” Hu Min asks a fellow worker.

“Honestly, I don’t really know. The Sui authorities kind of dragged me into this. My guess is that it will be a transport for a large military operation coming up. All I’ve heard from rumors is that the new Emperor, Emperor Yang, has cooked up some crazy plan that I’m still trying to digest. His plan is to avenge the loss we suffered against Korea 14 years ago. As you probably remember, that loss enraged the Emperor pretty badly, and I think that this battle has been in the midst of planning since the day we retreated.”

Two years earlier:

Emperor Yang (the guy who killed his father Emperor Wendi) is stroking his beard, sitting on his throne for hours.

“Sir, is everything alright?” His assistant Feng asks.

“Feng…” Emperor Yang says slowly in his raspy, smoke-scarred voice. “Do you remember the day…11 years ago. When we lost to Goguryeo? Do you remember how badly we embarrassed ourselves, our nation? When the great China lost to a small peninsula, to weaklings, inferior peasants! My father never got over that defeat… and neither will I. Feng, ever since I was crowned Emperor, I have been planning a revenge war on Goguryeo. I remember… the pure anger I felt 11 years ago, and nothing, you hear me? Nothing will get in the way of this plan; it will go down as the greatest invasion mankind has ever seen! We will build a massive canal from the North to the South of China, and prepare over a million trained troops, along with 2 million auxiliaries! I don’t care how many men it takes, Feng. Goguryeo will feel our wrath!”

After a brutally heated argument on whether or not to send the Sui troops to Goguryeo, the commanders decide to pursue Pyongyang, despite the possibility of running out of supplies.

Sure enough, the troops run out of resources: at the start of the battle, Sui troops are given 50 kilos worth of food that they carry in packs. A group of soldiers are sent to Pyongyang, but along the journey are forced to dump food to lighten the load. Hu Min is one of these soldiers.

It is midday, and the sun is out, blinding Hu Min, scorching his face. He and his companions are traveling to Pyongyang, with a 50 kilo pack of food. Hu Min has already gotten rid of 10 kilos worth of valuable food and resources, but a 40 kilo pack in 90 degree weather isn’t ideal either. Hu Min’s back is aching with soreness and pain, and his entire body is glazed with sweat and dirt. He dumps 5 kilos more from his bag, as the pain is almost unbearable. His legs are wobbling and struggling from days of walking, and his shoulders are numb. Because of the loss of resources, he has to ration each day’s meal out, knowing that he will be forced to dump more out later. This demoralizing journey is taking soldiers much longer to reach Pyongyang, and Hu Min, on little rest, is seeing triples by the time he reaches the destination. With lack of energy, sleep, and motivation, there is no way that Hu Min is fighting a battle after this. All he can think of is resting in his nice, cool, comfortable bed back at home, with his family.

After Hu Min and the Sui army set up a camp to settle just outside of Pyongyang, he sees a mysterious, unfamiliar man enter the camp. His name is General Eulji Mundeok, a Korean commander. Hu Min and others approach him, ready to attack.

“I come here in surrender and peace.” Mundeok said as he raised his hands in the air. “All I ask is that I tour this camp that you’ve set up.” As he is touring, Zhongwen, a Sui authority, claims that he has been instructed by Emperor Yang to capture Mundeok, but Liu, Zhongwen’s companion, thinks they should release him.

“What do you mean release him? He’s on the opposing side, you fool!”

“What harm can he do? He has surrendered and offered peace. It will be too much of a hassle to monitor him anyway, especially with how tired we all are!” Zhongwen disagrees, but doesn’t have the energy to get into a heated argument. Mundeok is somehow released, and after the exhausted Sui dynasty pursues Pyongyang, Mundeok re-attacks, leading several battles a day against the Sui, surrendering and retreating, luring in the army, and further exhausting them. The exhausted army is soon forced to retreat back to Sui, as the fortifications in Pyongyang seem impenetrable.

The Sui call on Lai Hu’er, a naval commander, to supply the army with food, but Goguryeo is always one step ahead of them.

Goguryeo calls on their trusty long-term commander, Seoung Jin, who is now nearing 60 years of age. He is now the naval commander, leading a group of ships against the Sui right outside of Pyongyang. Upon engagement, Sui ships crush Seoung’s ships, and very soon, Seoung realizes that his ships are no match for the FANG of the Sui, and retreat, forcing him to come up with a plan. But no need to fear, because due to his decades of experience, he comes up with an ingenious plan.

Once Goguryeo retreats, the Sui see this as an opportunity to advance to Pyongyang, with an even larger naval attack. Once they spot a castle, they find the gates open, a perfect opportunity to loot it. They loot and destroy Korean art and culture, but can’t finish before Seoung Jin and his naval army ambush the Sui during their looting session. They slam into the Sui, destroying several thousand ships, resulting in another success for Seoung. Confused, Lai, the Sui commander, retreats, but not before his army is decimated.

With neither food nor support, Hu Min and the Sui’s soldiers are not looking good. The remaining army has reached Salsu, and the Goguryeo army charges the Sui. Despite having little energy, Hu Min and his companions give everything they have left, and are starting to make a comeback. Their pursuit keeps going for months, but ultimately fizzles. Mundeok defends Goguryeo fortresses, and holds attacks against the Sui army and navy.

Hu Min is included in those soldiers making a last valiant attempt at victory. Although it is looking bleak, they move further into Goguryeo territory. Soon, the last straw is pulled in an ultimate culmination of all the attacks, when the Sui reaches Salsu, where Mundeok releases a dam on the Sui troops as they are crossing. Sui troops are flooded and drowned. As Hu Min sees the water crashing down on thousands of Sui troops, he slashes down one more Goguryeo troop, says his final prayers, and is swept by the crashing dam. Out of 305,000 Sui men that enter Pyongyang, only 2,700 return.