The War of 1812: A Tragic Fall and a Fledgling’s Flight

This essay references Allan W. Eckert’s A Sorrow in Our Heart, a 678-page biography on the Shawnee warrior Tecumseh which compiles over 850 sources in an attempt to provide as comprehensive of a depiction of the life of Tecumseh as possible. However, there are still things that no one knows for certain; for example, undocumented dialogue is completely made up, but Eckert aims to create it based on evidence from his over 850 sources.

I also reference John Sugden’s Tecumseh: A Life, a 30-year effort to create the first authoritative biography on Tecumseh to truly understand the almost mythical man in the history of both Native Americans and the United States of America. In Tecumseh: A Life, Sugden does not utilize creative nonfiction, only presenting documented dialogue.

In the final paragraph of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson introduced the members of the Second Continental Congress as “the Representatives of the united States of America.” Granted, the word “united” was not a part of the official name at that point, but the name stuck around. Not only did the Declaration of Independence challenge the idea of the role of government, but it also declared the thirteen colonies as separate from the United Kingdom.

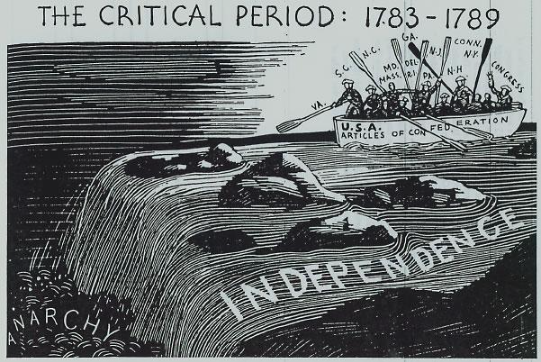

However, in that same paragraph, the unity is implied to be temporary, as after Jefferson refers to the colonies as the “united States of America,” he refers to the colonies as “Independent States.” There’s this sense of plurality here as opposed to unity. This sentiment makes sense as Jefferson later proved to be an antifederalist, supporting the disastrous Articles of Confederation (1783-1789),

and opposed the ratification of the Constitution. The Articles of Confederation were essentially a group of documents outlining a treaty of cooperation between thirteen sovereign republics (the thirteen former colonies). As a result, those six years when the Articles of Confederation reigned over the supposed “united States of America” were filled with chaos and not a lot of cooperation. Clearly, the states needed to unify under a strong, central government. Thus, the Constitution was born.

The Constitution created three branches of government: the executive, legislative and judicial branches. The American people had succeeded in laying the groundwork for the United States of America in which the federal government had significant power without creating a king. However, calling them “American” may be a bit generous due to the lack of national identity during this time period. People would refer to themselves not as Americans, but as citizens of their respective states. They called themselves New Yorkers, Virginians, Nutmeggers or Connecticuters, Pennsylvanians, Massachusettsans, but not Americans. However, with a war against their old oppressors on the horizon, could they unite in a new way, in the War of 1812?

As it turns out, the War of 1812 (1812-1814) quickly evolved into a fight for nationhood, but to fully understand this fight, one must look at the Shawnee.

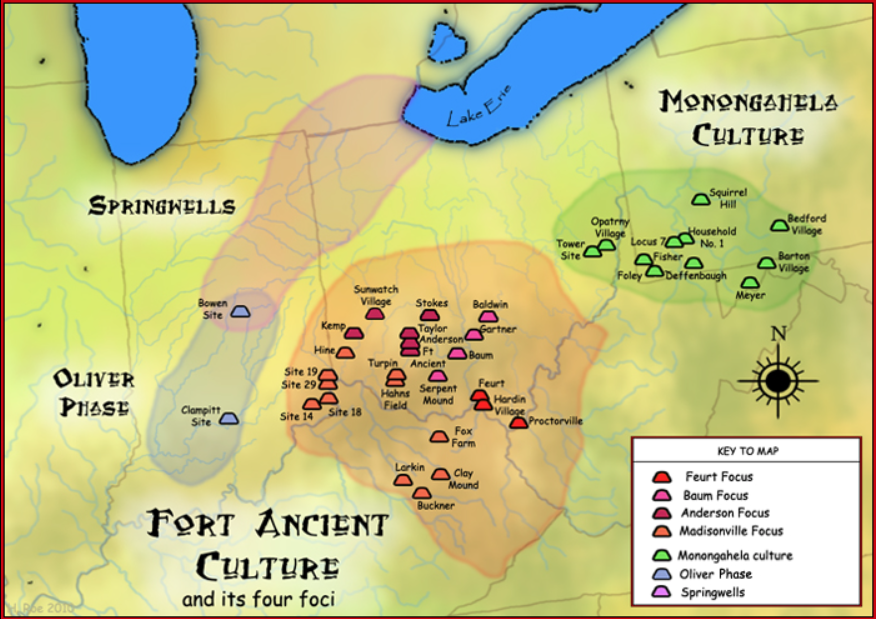

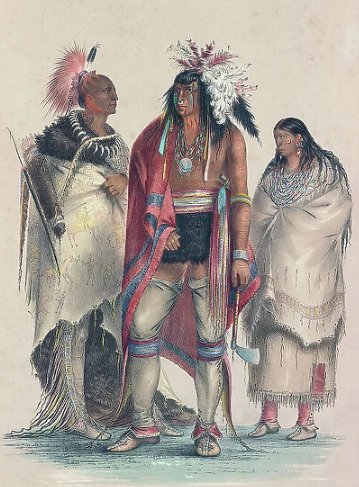

Historians debate the origins of the Shawnee nation; some historians claim that the Shawnee descend from the Fort Ancient culture of the Ohio River, and others link them to the Siouan-speaking tribes.

Diseases brought by the Spanish devastated the Fort Ancient people, and afterward, evidence shows that they moved into a more nomadic way of life, just like the Shawnee from the 1600s to the mid-1700s. Cultural similarities and Shawnee oral history link the Shawnee and the Fort Ancient people, but oral history also links the Shawnee to Siouan-speaking tribes. According to the Shawnee, however, they descend from the Algonquian-speaking nation of the Lenape, and the Algonquian nations of Canada consider the Shawnee to be a part of their own.

What historians do know for sure is that by the 17th century, the Shawnee were scattered across the area bounded by the Mississippi, modern-day Alabama, modern-day Ohio, and the Atlantic Ocean. The Shawnee were roaming mercenaries, moving in with tribes who requested their elite warriors for protection and moving out in search of the next battle. If the Shawnee were so scattered, then what did it even mean to be a Shawnee?

The Shawnee were “often with different factions within their own tribe supporting different factions of the whites”; however, they somehow managed to stay unified, “never allowing these diverse alliances to become hot warfare among themselves” (Eckert 9).

In another sense, they were organized. The Shawnee split themselves into five septs, and each sept had its own subchief, allowing for each sept to work as its own nation while following the orders of the Grand Council. Perhaps this system worked due to the relatively small population of the Shawnee, as estimates for the 1660s place the figure between 10,000 and 12,000.

The Shawnee rivaled the Iroquois, a five nation alliance concentrated in the Finger Lakes region (central New York), a tribe of nearly 12,000 as well. But they were eventually to settle, for a short period at least: one Iroquois-Shawnee conflict in 1690 won the Shawnee a homeland. In this conflict, the Iroquois declared war on the Miami, and the Miami sent out a cry for help, which the Shawnee answered. As a thanks, the Miami invited a group of Shawnee warriors to settle in the lands they held north of the Ohio River called the Scioto Valley. But in 1692, the group of Shawnee had to leave it and join the Delawares on the lower Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania.

But with white settlers flocking into Pennsylvania, the Shawnee looked back west. Their leader, Opeththa, believed that the Scioto Valley was the land promised to the Shawnee by the Great Spirit hundreds of generations ago. He convinced the Grand Council to send a delegation to the Miami. The Miami agreed to give up the land again, as they wanted to place the Shawnee in between them and the growing numbers of European settlers. Now that the Shawnee finally had their land, could they fend off the white settlers?

Four wars outline this struggle: the French and Indian War (1754-1763), the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), the Northwest Indian War (1786-1795), and the War of 1812 (1812-1814).

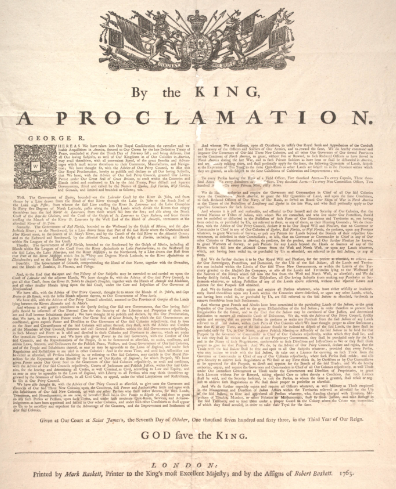

The Shawnee historically had horrible luck with choosing sides. The Shawnee sided with the French in the French and Indian War: they lost. The British issued the Proclamation of 1763,

which blocked settlement past the Appalachians, and the boundary line should have worked, but the British made little effort to enforce it. However, the Shawnee’s problems came from the settlers and not the British, so when the American Revolutionary War broke out, the Shawnee sided with the British: they lost. Not only did the US gain its independence, but it also officially gained the territory past the Appalachians. To defend their territory, the Shawnee joined with other tribes in the region to form the Northwestern Confederacy, leading to the Northwest Indian War: they lost.

Think of it like betting in sports. Pick someone to win and someone to lose. The Shawnee bet on the French in the French and Indian War, and they lost to the British. The Shawnee bet on the British in the American Revolutionary War, and they lost to the Americans. Then, a group of angry sports fans (not the Cleveland Indians, but the Northwest Confederacy) decided to ambush the Americans and the Shawnee joined in, and they got arrested. However, with the War of 1812 bringing Britain and America against each other again, could the Shawnee capitalize on this final opportunity? Could they successfully gamble it all?

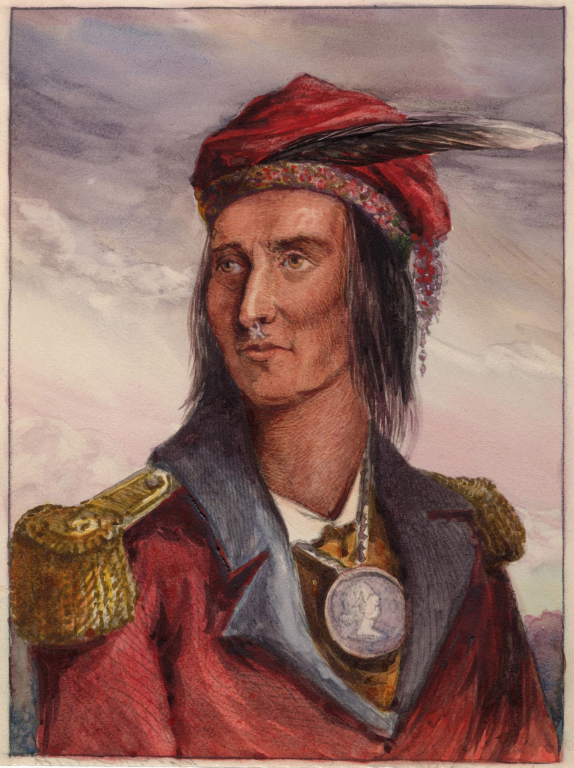

Tecumseh (1768-1813) is the most important figure in organizing this final opportunity. His father, Chief Pucksinwah, died in the Battle of Point Pleasant in 1774 when Tecumseh was six, and the boy swore to take down the colonists who robbed him of his father; as he grew older, his anti-American sentiments grew even stronger.

He went on his first mission when he was 10, and what did he do? He fled in fright. Ashamed, he vowed to stand his ground. In the years to follow, he would only retreat at the orders of his superiors. At 15, he attended an intertribal conference where speakers established this idea that Indian lands belong to all tribes, and no land could be ceded to the United States without the agreement of all tribes. The tribes attending this conference formed the Northwest Confederacy. In 1785, the Northwest Confederacy conducted a series of raids along the Ohio River, kicking off the Northwest Indian War. In 1794, he fought in the Battle of Fallen Timbers, a Native American ambush that turned into a crushing blow for the Northwest Confederacy. In 1795, The Northwest Confederacy sued for peace and signed the Treaty of Greenville (1795).

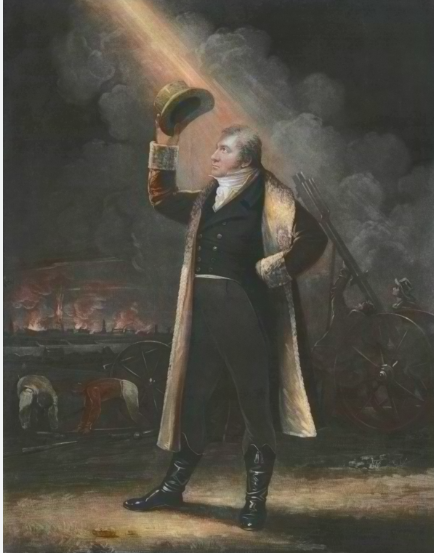

Painting by R. F. Zogbaum

After the treaty, Tecumseh split off from the peace-minded majority in the Shawnee and took some of his followers with him. He cobbled together Tecumseh’s Confederacy—a pan-Indian alliance built to eventually go to war against the whites.

In 1805, Tecumseh’s brother, Tenskwatawa (1775-1837), connected with his inner prophetic potential: he drank too much alcohol. People thought he was dead, so they prepared his body for burial. While preparing his body for burial, he woke up and recounted a vision of two worlds: he’d seen a utopian world for those who lived according to their tribal customs, and a hellish one for those who accepted Euro-American customs. After surviving that first vision, he started gathering religious appeal for resistance against the whites. He promoted tribal conservatism, resisting attempts to force Euro-American customs onto Native Americans and, of course, resisting American westward expansion.

He became known as “The Prophet,” and in 1808, with Tecumseh, he founded the capital of Tecumseh’s confederacy, Prophetstown, in modern-day Indiana.

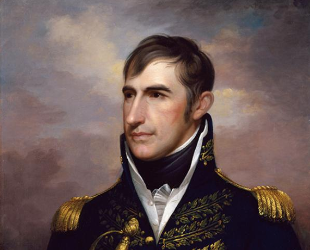

In Prophetstown, he and Tecumseh gathered followers from many different tribes, including the Shawnee and the Chickamauga. While Tecumseh built his confederacy, William Henry Harrison was also making moves. As the governor of the Indiana Territory, William Henry Harrison wanted to clear out the Indians residing in his territory, so he bought them out.

What Tecumseh is known for today aside from the battles he fought is his oratorial skills—the speeches he gave. As a result, he is perhaps the most revered Native American of all time for not only his actions, but also his message. His extraordinary ability to command his words and convey his ideas to his supporters and opponents immortalized him.

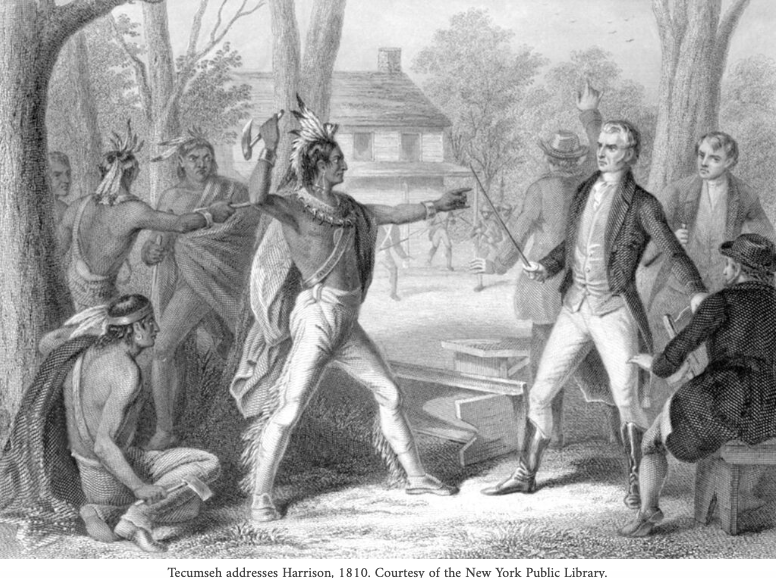

On August 20, 1810, Tecumseh, 42, spoke with Indiana governor William Henry Harrison about the Treaty of Fort Wayne, and his words would become known as his “Address to William Henry Harrison on Selling a Country”:

“Houses are built for you to hold councils in. Indians hold theirs in the open air. I am a Shawnee. My forefathers were warriors. Their son is a warrior. From them I take my only existence. From my tribe I take nothing. I have made myself what I am. And I would that I could make the red people as great as the conceptions of my own mind, when I think of the Great Spirit that rules over us all. I would not then come to Governor Harrison to ask him to tear up the treaty [the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, which gave the United States parts of the Northwest Territory]. But I would say to him, ‘Brother, you have the liberty to return to your own country.’ You wish to prevent the Indians from doing as we wish them, to unite and let them consider their lands as a common property of the whole. You take the tribes aside and advise them not to come into this measure. You want by your distinctions of Indian tribes, in allotting to each a particular, to make them war with each other. You never see an Indian endeavor to make the white people do this. You are continually driving the red people, when at last you will drive them into the great lake [Lake Michigan], where they can neither stand nor work.”

Tecumseh tells Harrison that what he is doing is wrong in order to avoid war. He confronts Harrison about his dividing and conquering tactic, saying that he wishes “to prevent the Indians from doing as we [Tecumseh and his confederacy] wish them, to unite and let them consider their lands as a common of the whole [of all Indians].” Then, he says that, “You never see an Indian endeavor to make the white people do this,” essentially telling Harrison that he is the villain of this story—that he is attacking the Indian tribes unprovoked. Tecumseh lays out Harrison’s cards right in front of him in order to show him exactly why he is not only fighting for himself, but for the Indian people, in a just crusade against a conqueror.

The use of “liberty” and “unite” to shame Harrison is also brilliant verbal irony. Tecumseh turns fundamental parts of the Declaration of Independence against Harrison. The Declaration of Independence claims liberty to be an “unalienable right,” while the document as a whole symbolizes the unification of the thirteen colonies into the “united States of America.”

He continues:

“Since my residence at Tippecanoe [Prophetstown], we have endeavored to level all distinctions, to destroy [traitorous] village chiefs, by whom all mischiefs are done. It is they who sell their land to the Americans. Brother, this land that was sold, and the goods that was [sic] given for it, was only done by a few. In the future we are prepared to punish those who propose to sell land to the Americans… “

Tecumseh’s words exude a radical pan-Indianism. He clearly intended to unite the Indian tribes against the United States as he criticized the village chiefs, a few people who made decisions for many. He was prepared to take drastic measures to achieve this goal.

Tecumseh also openly states that his confederacy’s purpose is to defend the land of the Indian tribes, and if he needed to, he would attack the United States. Were the mighty words matched with military strength? Well, Tecumseh’s confederacy required vastly more strength to go toe-to-toe with the US, so Tecumseh visited the southern tribes to gain their support. Seizing this opportunity, Harrison organized his attack.

During his absence, Tecumseh had put the tippler Tenskwatawa in charge of Prophetstown. On November 6, Harrison and his militia forces approached Prophetstown to negotiate with Tenskwatawa, but the 1,000 militiamen he brought showed that he intended to fight. Tenskwatawa attempted to murder Harrison in his tent, assuring the warriors that the Great Spirit would protect them from any harm. The warriors did not succeed. The next day, Harrison burned Prophetstown.

Tecumseh’s War began at that: the Battle of Tippecanoe (another name for Prophetstown), and this battle delivered a major blow to his confederacy. In seven months, he regathered his strength, rebuilding Prophetstown and amassing 800 warriors in his capital. When he heard of a war between the British and the Americans, betting on the British was his only choice. He couldn’t stay out of it; what if this was his last opportunity? As a result, Tecumseh joined the British in the recently-declared War of 1812, his hand forced into risking it all. At this time, Tecumseh’s confederacy and its allies numbered around 3,500 warriors. He headed toward Fort Malden, where he was to meet up with Major General Sir Isaac Brock to plan a siege on Fort Detroit, headed by General William Hull.

General William Hull (1753-1825) had been a lieutenant colonel in the Revolutionary War, and the US pulled him out of retirement for the War of 1812. Experience is valuable in war, and in his prime, Hull fought in key Revolutionary War battles like Saratoga, Trenton, and Princeton, and he fought to defend Fort Ticonderoga and Boston. But it had been over two decades since the Revolutionary War: he was also inexperienced with fighting, and intensely fearful of Native Americans, an exploitable weakness.

Hull’s campaign started off on the wrong foot. The US government had not informed him of the current state of war when he sent a schooner, Cuyahoga, up the Detroit River with “all of the army’s excess baggage, entrenching tools… musical instruments… Some thirty officers and men… all of [the President’s] papers, orders, notes, correspondence, accounts, and field reports” (Eckert 574). Unfortunately, the British controlled the Detroit River. In the Battle of Amherstburg, the British defeated the severely outmatched Cuyahoga. The British boarded the vessel and seized everything. With the British in possession of Hull’s plans, the invasion of Canada was doomed from the start.

After stopping in Detroit, Hull crossed the Detroit River and entered Canada on July 12, 1812. The lack of artillery, supplies, and efficient communication lines plagued his invasion. The invasion lasted less than a month, ending on August 7, 1812, after Tecumseh’s warriors ambushed an American supply convoy, causing Hull to retreat. In the end, Hull had ended up right where he started: with over 2,000 men stuck in Fort Detroit.

Tecumseh began attacking Hull’s supply line. American forces met Tecumseh’s at the Battle of Brownstown (August 5, 1812) and the Battle of Maguaga (August 9, 1812), and perhaps Hull was rightfully scared of Tecumseh’s men. Those battles were quick ambushes which inflicted disproportionate casualties on the US military. At Brownstown, the US forces outnumbered Tecumseh’s 8-to-1, but the US suffered around 100 casualties (70 of which were MIA while the number of men killed and wounded is not clear) while Tecumseh suffered just one dead. At Maguaga the US forces outnumbered the British-Indian alliances’ 3-to-1 and their casualties also outnumbered the British-Indian alliances’ 3-to-1!

Around this time, Tecumseh met up with Major General Sir Isaac Brock. Tecumseh gained a lot of respect for Brock when he learned of the latter’s plan to attack Detroit. Glad that a British man was finally taking action, he was more than willing to cooperate (Sugden, 336). Canadian historians like to claim that Tecumseh said “This is a man!” in regards to Brock (Sugden 336). Tecumseh’s prowess as a leader and a warrior also gained him Brock’s respect. Together, they devised a plan to take Fort Detroit, and they put that plan into action on August 15, 1812.

Brock led the British regulars and Canadian militia while Tecumseh led his warriors, and they came up with a clever strategy: bluff and deception. Since Hull’s militia nearly outnumbered the British-Canadian-Indian alliance 2-to-1, they needed to trick Hull into thinking that the numbers were more even than they actually were. How did they achieve such deception? Why, they just had Tecumseh’s warriors run through an opening in the forest repeatedly to make it seem like there was a massive Native American presence at Fort Detroit. In other words, although Hull outnumbered Brock and Tecumseh’s forces 2-to-1 while being in the safety of a fort, Hull thought he was outnumbered.

Also, Brock sent Hull a summons of surrender, in which he said, “It is far from my intention to enter into a war of extermination, but you must be aware that the numerous body of Indians… will be beyond my command once the contest commences” (602). In other words, he threatened Hull with a massacre, and Hull’s timbers shivered, so he called a detachment of 350 militiamen back to the fort.

Brock originally planned on drawing Hull out of the fort, but upon hearing news of these reinforcements coming to aid Hull, Brock knew that he had to win quickly. Consequently, Brock drew up plans to storm the fort and take it the next day.

The next day, on August 16, 1812, Tecumseh and his warriors entered the Detroit village to prevent its inhabitants from joining the defense while the British army assaulted the fort. Tecumseh met little resistance. Brock’s column moved into a ravine and prepared to assault the fort against the American batteries. However, at 10 AM, the battlefield fell silent as the American artillery stopped firing on Brock’s position. A white flag hung on the side of the fort. Hull had surrendered (Sugden 340).

The Siege of Detroit put Tecumseh’s pan-Indian message on full blast. It energized the Indian tribes as many pro-American Indians switched sides (608). Warriors from tribes all over the northeast joined his cause, and Tecumseh’s words “were as revered as though they had been uttered by Moneto [the Supreme Being]” (608). Quickly, his ragtag bunch of thrill-seeking warriors had grown into the massive pan-Indian alliance Tecumseh had dreamed of united by one cause: defeat the United States. Could they give the United States a taste of their own medicine and successfully unite their different cultures and views to take down their common enemy? Could they establish a pan-Indian nation to fight the United States and deter any future attempts to conquer their territory? Could they establish the first (true) Native American nation?

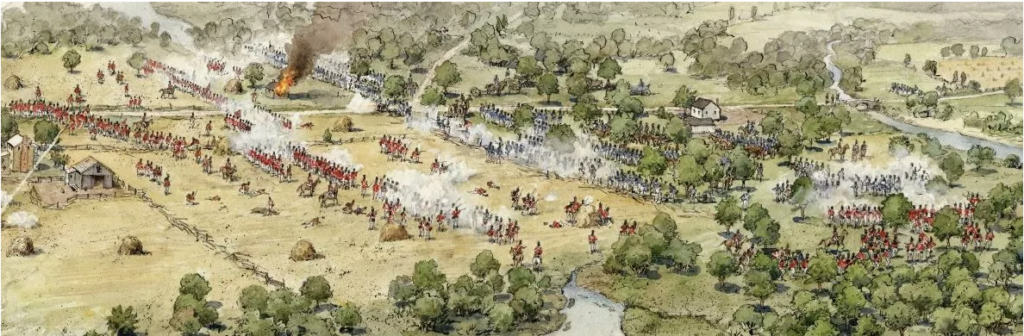

Perhaps the sheer size of a united group of Indian tribes would have forced them to organize with a centralized government and attempt to write a constitution like the United States. Perhaps that would have been the first Indian state. Then, Tecumseh’s War would have been studied not as a flashpoint in American history, but as a key event in another nation’s birth. However, anyone who has seen a map knows that the United States owns the Midwest, so what went wrong? The final battle of Tecumseh’s War was the Battle of the Thames on October 5, 1813. He lost. Not only that, but it was the British failure to push the American forces toward the forest wherein lay Tecumseh’s warriors that lost the battle. Tecumseh’s confederacy was integral to the victory that may have saved Canada and bought essential time for the British, yet when Tecumseh needed the British to pull their weight at the Battle of the Thames, they did not. A year before the end of the War of 1812 came the end of Tecumseh’s dreams for a pan-Indian alliance strong enough to tango with the fledgling United States.

The threat of Tecumseh’s dreams of a pan-Indian nation-state resulted in him being squashed under the weight of the rapidly growing, albeit young, United States. However, would Tecumseh’s tragic fall pave the way for the flight of the fledgling United States and bring unity to the imperfect union?

So now that we see that Tecumseh, despite his powerful words, was not a phoenix, what was the climax of the War of 1812, and how did the fledgling USA become an eagle?

The year is 1814. The month is September. Nineteen days ago, the British army rolled into Washington, D.C. and burned it to the ground. Things are not looking up for the US. Other than a few naval victories courtesy of the USS Constitution, the US has seen little success and a lot of failure in the War of 1812.

On the bright side, Thomas Macdonough secured a key naval victory for the US in Lake Champlain and ended British hopes of invading New York and Vermont. Now, with Baltimore under fire, could the US prove that it can win a major battle on land? Three battles made up the defense of Baltimore (September 12-15, 1814): the Battle of North Point (September 12), the Battle of Hampstead Hill (September 13), and the Battle of Fort McHenry (September 13-14).

The Battle of Hampstead Hill and the Battle of Fort McHenry occurred at the same time, as the British attempted a two-prong attack on Baltimore. Before these two battles, the British had fought US troops at North Point in which the US troops retreated to Hampstead Hill to mount their defense. However, placed along the coast was Fort McHenry which played the crucial role of preventing British naval support from assisting at Hampstead Hill.

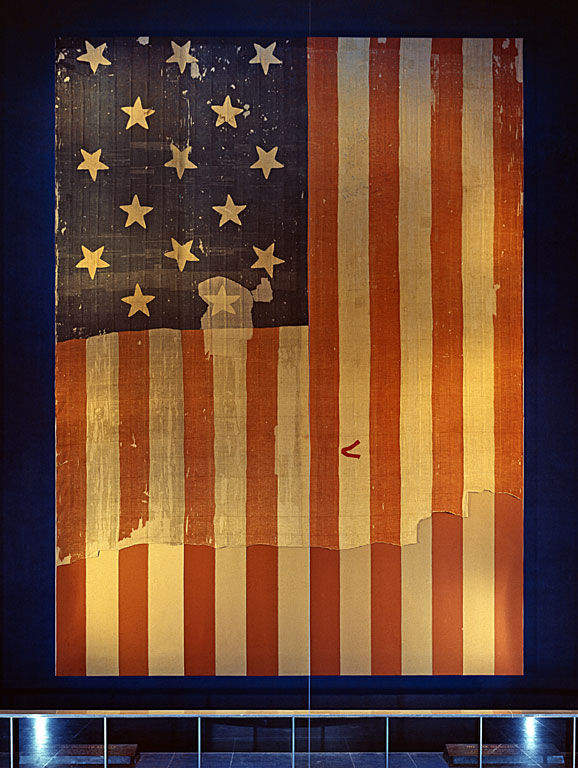

Thus, the British army advanced on Hampstead Hill while the British navy bombed Fort McHenry, hoping for a surrender. Fort McHenry had about 1,000 men manning the defense under the command of Major George Armistead. The fort’s walls had been recently fortified, and the Americans had sunk merchant ships at the entrance to the Baltimore Harbor to block any moves by the British to use it to attack. On a truce ship sat Francis Scott Key, who had just negotiated for a prisoner of war and was being temporarily detained because he had gathered too much intel on the British invasion of Baltimore.

He watched as the HMS Erebus fired Congreve rockets, which lit up the sky with a red glare.

He watched as mortar shells, fired from bomb vessels Terror, Volcano, Meteor, Devastation, and Aetna, burst in the air. He watched as the explosive projectiles lit up the American flag, tattered yet still proudly waving the stars and stripes above the fort. For the next 25 hours, he watched as British vessels fired round after round of cannonballs, launching a total between fifteen and eight hundred, but the fort and its one thousand men held strong.

By the morning of September 14th, the British started to retreat, and the oversized star-spangled banner waved over the land of the free and the home of the brave. The moment Key was released, he wrote a poem inspired by the battle on the back of an envelope. Not long after the battle, newspapers all around America published the poem, and when a music printer named it “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the name stuck.

O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hail’d at the twilight’s last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight

O’er the ramparts we watch’d were so gallantly streaming?

And the rocket’s red glare, the bomb bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there,

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

On the shore dimly seen through the mists of the deep

Where the foe’s haughty host in dread silence reposes,

What is that which the breeze, o’er the towering steep,

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses?

Now it catches the gleam of the morning’s first beam,

In full glory reflected now shines in the stream,

‘Tis the star-spangled banner – O long may it wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore,

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion

A home and a Country should leave us no more?

Their blood has wash’d out their foul footstep’s pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

O thus be it ever when freemen shall stand

Between their lov’d home and the war’s desolation!

Blest with vict’ry and peace may the heav’n rescued land

Praise the power that hath made and preserv’d us a nation!

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto – “In God is our trust,”

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Why exactly did Fort McHenry send such a powerful message? Why exactly was Fort McHenry so galvanizing? How did a poem about the battle become synonymous with the eagle’s cry—with freedom, with courage, with bravery, with America? Perhaps it was the message of America’s second triumph over Britain—the most powerful nation in the world. Perhaps it was the message of the resilience of the American soul.

The very context of the song is inspiring; the classic story of the underdog—of the little guy holding his ground against a giant. Also, Francis Scott Key was a lawyer who accidentally penned the national anthem. A key part of the American identity is the belief that you can be anything, and having a national anthem that’s written by a lawyer who was just observing what happened at a battle? That’s just American.

The Star-Spangled Banner perfectly represents the colors of well, the star-spangled banner. Red can represent hardiness and valor, white purity (in the sense that America is pure from the influence of other countries), and blue can represent vigilance and perseverance. The Star-Spangled Banner is essentially the Battle of Fort McHenry told in the form of a poem, and of the thousand hardy, valorous, vigilant, perseverant, men who held the fort for the independence of the United States.

The War of 1812 brought the United States together, with its end kicking off the Era of Good Feelings (1815-1825), a period of widespread national unity; people were finally calling themselves Americans.

On the other hand, the war devastated the Native American peoples, officially kicking their ally, the British out of American territory and resulting in the fall of Tecumseh, one of their greatest leaders. The United States unified at the cost of the shattering of the Native American peoples, which begs the question: what is the cost of national unity? With the current rapid polarization of American politics, does America need another war? In other words, must unity come at the cost of others, or can the state come together to peacefully save the nation?

Battle of the Thames and the death of Tecumseh, by the Kentucky mounted volunteers led by Colonel Richard M. Johnson, 5th Oct. 1813. Lithograph c. 1833. Image Courtesy of the Library of Congress