The Self-Deprecating Humor of Ohio, Maine, and New Jersey

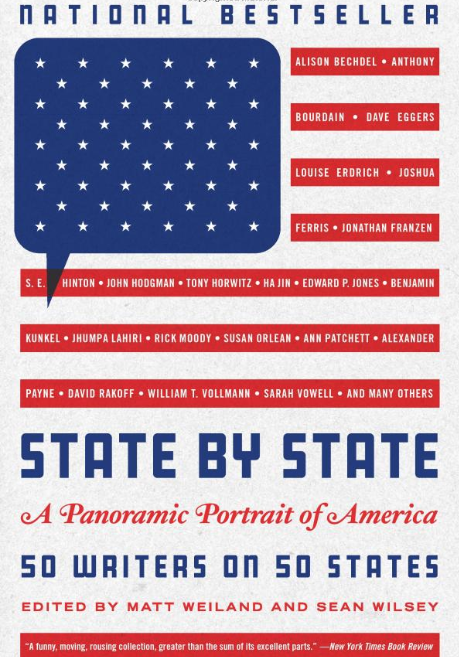

In 2008, Sean Wilsey and Matt Weiland came together to write a book: a collection of travel guides, narratives, biographies, and stories. State by State: a Panoramic Portrait of America, was to be a road trip in written form to help Americans better understand America. This idea was inspired by a collection of books already published in the 1930s called the WPA American Guide series of the Federal Writers’ Project. These guides brought together some of America’s best writers to write down everything there is to know, each state running more than 500 pages and requiring a total of twenty-seven million dollars of federal funding. Wilsey and Weiland decided on one singular book instead of a collection of them and instead of a travel guide, they asked their writers for “a story about your state, the more personal the better, something that captures the essence of the place. Not the kind of story one hears in a musty lecture hall or one reads in the dusty pages of an encyclopedia.” The goal was not to have a “beauty contest full of partisan arguments for the superiority of one’s state,” but rather a full portrait of the state leaving not a single inch unpainted, conveying “the good, the bad, the ugly.”

The foundations of this book are Weiland and Wilsey’s conviction and the hunch. The conviction is that we, as Americans, know embarrassingly little regarding our country, and only the largely commercialized parts: “so many mirrors and yet we know ourselves so poorly!” Weiland believes it takes a tragedy for us to take a second look at other states and lists examples, some recent (2008). “Who hasn’t marveled at the richness of lives we don’t know?” The hunch is that every state has its own identity, whether it be landscape, politics, or cultural preference, and that every person is defined by their home state. One aspect of the hunch is how your home state reflects your self-esteem – specifically how you look down on yourself for the blandness or lameness of where you were born.

A few states in the U.S.A have an inferiority complex, possibly due to location or status or lack of exciting fun facts. Some writers in State by State embraced this complex and embedded it throughout their essays. The author of Ohio, Susan Orlean, described Ohio as: “A place with a lot of people, a fair amount of power, considerable wealth, great accomplishment, but an aching lack of charisma…”. Growing up, Orlean was disappointed in her state and felt as if she needed to prove she was special. “So my context—and by extension, my personality— was Ohio, and that made me feel like I was expected to be mild, productive, and utterly normal—so I grasped for anything that would make being an Ohioan more dazzling.” For Maine, Heidi Julavits spoke lovingly about the terrible parts of her hometown, the denial of doctors and medicine, the Libertarian Mainer impulse to live and let live, the exclusion of the “Far Aways” and the rivetingly boring conversation topics like in-floor heating. In her summary, Julavitis said, “Ironically, it’s the innately hostile quality of the state and its inhabitants that makes the place the Vacationland it undeniably is. Because who doesn’t want the bull**** cut clear through by an ice storm? Who doesn’t want to feel that they are missing something, or that they’re being excluded from something, or that the boat left without them? and is never coming back?” There’s also New Jersey. Anthony Bourdain writes “that we kind of suck—and that, regardless, we celebrate [our] state.” These three states, Ohio, Maine, and New Jersey, acknowledge and poke fun at their state’s flaws while also adding to the conviction of the book – that the depiction of one’s home state is the best way to understand a state’s complexity.

Susan Orlean was born on October 31, 1955, in Cleveland Ohio. She has two siblings, David and Debra, and her father was an attorney. She was born and raised in Ohio, had a “happy and relatively uneventful childhood,” then went to the University of Michigan and graduated with honors in 1976. After moving to Portland, OR, she was thinking of becoming a lawyer when she stumbled upon a writing job for a small magazine which later led to another job for the Willamette weekly newspaper. Her career grew as she started publishing for magazines including Rolling Stone, The Village Voice, and Vogue. After 6 years she moved to Boston and worked for the Boston Phoenix and later for the Boston Globe Sunday Magazine. And after moving for the final time, she began writing for The New Yorker magazine. Some books she has written include Saturday Night (1990), The Orchid Thief (1998), and Rin Tin Tin: The Life and the Legend (2011). In the latter, Orlean writes a beautiful biography for one of the greatest dogs of all time, Rin Tin Tin. This German shepherd almost won an Oscar with the highest vote for best actor, however, the academy “recalculated” and the award was given to Emil Jannings. Orlean details the entire life of Rin Tin Tin from when he was found on the war-torn battlefield in WWI, through his worldwide fame, starring in twenty-seven Hollywood movies, and to his death where he now lays in Asnières-sur-Seine, France with his squeaky doll.

Orlean starts off her essay by debunking myths of Ohio like the flatness of the land, the mighty cornfields, the “hard, nasal, cawing” Ohioan accent, and its Midwesternness. Orleans explains that Ohio is actually quite bumpy, the cornfields’ vastness are nothing compared to the General Motors plant in Lordstown, that the Ohioan accent is a mix of surrounding states, and that the entirety of Ohio should be divided and absorbed into neighboring states because technically it’s the “West-of-Eastern/East-of-Western/North-of-Southern/Mid-Rustbelt.” According to Susan Orleans, Ohio’s character is one that “conveys a certain regularness, a lack of wild distinction, a muting of idiosyncratic extreme… a sampling of nearly every American quality and landscape but it levels out to something quietly and pleasantly featureless rather than creating a crazy quilt of miscellany.” As of the census of Agriculture in 2017, Ohio ranked fifth in number of farms with 77,805 spanning approximately fourteen million acres and ranked 16th in agricultural sales, totaling to nine billion. Orlean’s generalization for the state is, “a place with a lot of people, a fair amount of power, considerable wealth, great accomplishment, but an aching lack of charisma.” To its perhaps overlooked credit, the WPA Guide to Ohio commented: “The life of practically everyone in the Nation has been touched, and in some degree made more livable, by the products of Buckeye enterprise.”

In his book, The Book of America: Inside the Fifty States Today (1984), Jerry Hagstrom wrote in his first sentence on the chapter on Ohio: “Ohio, hung up about its own identity (East to Westerners, West to Easterners), and the epitome of middle-class society, is the least distinctive of the great industrial states of the U.S.A.” Jerry Hagstrom’s comment brooks no room for argument as he described the humdrum state. Orlean obviously agrees with Hagstrom, for she was hung up too. She felt like she had to be just as dull as Ohio. And yet she also felt obligated to make Ohio stand out, even telling people that her mother dated Sam Sheppard, who was a murderer from nearby, the inspiration for the movie The Fugitive. Weiland’s conviction is that people only remember another state besides their own, except when it is attached to a tragedy, and Orleans using Sheppard to impress people only reinforces that.

In his preface, Weiland writes, “Often it takes a tragedy to remind us so: when residents of the Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans stand dazed on their rooftops wondering why the flood water came so fast and the drinking water so slow; when coal miners are rescued in West Virginia or entombed in Utah.” In fact, in 1969, Ohio was infamous for its terrible waters, with so much industrial gunk that it ignited and produced flames 5 stories high. This tragedy brought a lot of attention to the Buckeye State and the dealing with the Great Lakes’ water purity. Orlean even says matter-of-factly, “Ohio with clean water is a better place by far, but gives you much less to talk about.” And finally, Orlean shares the place where she grew up: Chagrin Boulevard near the Chagrin River. This name made Orlean feel even more obligated than before to prove Ohio’s distinction and specialness to compensate for the fact that she grew up in an area with a name synonymous with disappointment. In her head, she imagined that an explorer was looking for an exciting place but had to settle down in Ohio and so named it Chagrin. Despite later discovering that it was named by the Erie Indians and meant Clear Water, she always held the image of the explorer looking around with the sour taste of disappointment in his mouth, breathing a sigh of resignation, “swallowing his little nub of disappointment,” and setting up camp.

Heidi Suzanne Julavits was born on April 20th, 1969 in Portland, Maine. She graduated from Dartmouth College in 1990 and traveled the world before settling in the beautiful city of San Francisco (full disclosure: San Francisco is my hometown). She worked many jobs including as English teacher, waitress, and fashion copywriter. She then moved back east and attended Columbia University’s graduate writing program and graduated with an MFA. Julavits was a founding editor of The Believer magazine, and wrote the debuting article “Rejoice! Believe! Be Strong and Read Hard!” Julavits also wrote four novels including The Mineral Palace (2000), The Effect of Living Backwards (2003), The Uses of Enchantment (2006), and The Vanishers (2012). She currently teaches at Columbia University and lives in Maine with her husband, Ben Marcus (a writer as well), and her two children. Julavits’ debut novel, The Mineral Palace, takes place in Colorado during the Dust Bowl years. This novel carries a sad tone to it as the grimy dust clouds settled above reflect the mood of the inhabitants of the small town. The protagonist has just moved there, and as a society reporter, meets people from the town ranging from the high snobbish class to the prostitutes. She learns more and more about the place she’s staying in, her seven-week-old son, her marriage, and her inner demons.

Julavits, the author of “Maine”, begins with a comment that immediately captures the reader’s attention. “By the time this essay is published I will already be in hiding.” The reason why she needs to hide is that in writing this essay, she is establishing herself as an authority and according to her, there’s nothing Mainers hate more than an authority. Ironically, their motto is Dirigo which means “I Lead”! She explains that when she asked for advice about boat building from a professional boat builder, he first went out of his way to explain that he knew practically nothing about the profession and that anyone could do it. Julavits then describes the living conditions of Maine, and how in a state known for being a vacationland, there are more obese people than in any other New England state, the average temperature on the coast is 46 degrees, and in 2005, the only state poorer than Maine was Louisiana, “meaning, the only state worse off financially was a state that suffered the most crippling natural disaster in the history of this country”.

Mainers are categorized as either Natives or From Aways. However, the reasons for calling someone a From Aways were incredibly subjective and relative. Julavits, who was born in Portland, left when she was 18 and returned when she was 33 and is recognized as a From Away in her home state. Even in an obituary, a woman who had lived in Maine for her entire life (90+ years), except for the first 3 weeks, was always known in her community as the Woman From Away. Maine has low expectations of From Aways in that “you’re meant to screw up regularly at great cost to your homeowner’s insurance”. From Aways are of course a source of entertainment and gossip for the Natives.

When Julavits first came back to Maine there was an incident with burst pipes in her room and months later when shopping at a bookstore 12 miles away she was recognized as the From Away with the burst pipe. In the next section, Julavits gives us a 27-line paragraph about the topics that are discussed over dinner in Maine: “You will talk about firewood… the benefits of in-floor heating, and the R-value of your new insulation and whether or not you should pre-buy your furnace oil… unconventional uses for your Shop-Vac… pouring dye in your toilet… septic mounds and how to landscape them.”

Next, a story about Stan and Gitano, a long feud between neighbors. “Note: What follows is accurate only to the degree that the gossip surrounding the battle between Gitano and Stano can be considered accurate… I’d put the accuracy percentage at about 82.” Gitano, a man well-versed in crime, drugs, drinking, and troublemaking, has been living with an old lady, and rumors say he has psychologically imprisoned her while doing odd painting jobs, both murals and housepainting, around the town. One painting angered a restauranteur named Stan and he and Gitano got into an argument. Gitano then painted a sign “aimed at Stan’s customers” that read “For the amount of money you’re spending on dinner you could feed a starving family for a month.” In a rage, Stan attempted to get Gitano removed from the town but Gitano’s response was to run for town selectman. Both failed. Gitano’s abuse continued. He lashed out at a sweet woman “with a green thumb” who lived nearby, for no apparent reason. He painted on his house facing the woman’s house the words “GO HOME.” She must have been a From Away.

Anthony Michael Bourdain was born on June 25th, 1956, in New York and was raised in New Jersey. Bourdain’s interest in food started as a young boy when he first tried an oyster in France. He would later graduate from the Culinary Institute of America in 1978 and move to New York City where he started many successful restaurants. During his time as a chef, he also wrote two crime novels: Bone in the Throat (1995) and Gone Bamboo (1997). Bone in the Throat was Bourdain’s first novel; set in the streets of Manhattan, is filled with murder and mayhem. Google Books describes it as “street smart and spicy with drugged-up savvy, foul-mouthed Feds, and salty mob speak… and a plot with more twists than a plate of spaghetti.” Bourdain then published an article in The New Yorker exposing the ugly side of the restaurant world and he was seen by the public for the first time. This exposé grew until it became a memoir, then a show, and finally, an hour-long cable program called No Reservations. This increase in popularity led Bourdain to travel the world with guest appearances on other travel shows. His shows won Emmy Awards and he guest-judged for many cooking competitions. Bourdain died by suicide on June 8th, 2018.

Anthony Bourdain starts his New Jersey essay with mentioning the attempt of New Jerseyites to replace the official state song, “I am from New Jersey”, a peppy tune, with Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run.” Although Bruce Springsteen (according to Bourdain), is their proudest and most famous citizen, the song itself is about getting out of New Jersey. So from the start of the essay, Bourdain implies the lack of seriousness that New Jerseyites view themselves with, or as he says, “that we kind of suck – and that, regardless, we celebrate that state.”

Bourdain writes that the inferiority complex that Jerseyites have when talking to New Yorkers partially emerge because of the smells coming from “the swamps” which are ironically called Meadowlands, and the “even more sinister odors from the refineries along the Turnpike.” Bourdain theorized that “the inferiority complex that Jerseyites famously acquire when meeting New Yorkers has its roots in a vestigial awareness that we come from a state that smells.” The residents fortunate enough to live close but not to be New Yorkers were defined from birth as “others” because they were in the shadow of New York City.

New Jersey even has their rip-off of Bigfoot known as the Jersey Devil and the 1946 WPA Guide to New Jersey made it sound “no more threatening than a kind of flying lassie” with its awkward components: “the head of a collie dog, the face of a horse, the body of a kangaroo, the wings of a bat and the disposition of a lamb.”

Bourdain’s hometown was a small middle-class community called Leonia, where everyone had the same amount of money and every year his family and many other families would vacation to Long Beach Island, New Jersey, for a week or two.

Leonia was a paradise for kids like Bourdain who could “run wild, build forts, pick trash and set off fireworks” in Highwood Hills which was a small wooded area, and “in the vast swamps where we could detonate more serious explosives, perpetrate relatively harmless acts of arson and wallow in the chocolate pudding-like mud that, on reflection, was no doubt loaded with heavy metals.” As Bourdain’s explosive antics got more and more dangerous he exclaims, “it’s a Jersey miracle I didn’t get my young ass and nut-sack full of shrapnel.” However, when he moved to a much larger and wealthier private school called Englewood he meets a new group of people accustomed to tennis courts, carefree lifestyles, unused pools, money to spare, and a smell of “laundry, soap, and money.” This interaction, much to Bourdain’s shame, caused him to drop all his old friends whom he noticed smelled like bacon and of family kitchens. In his later childhood he describes himself and his friends becoming a “transient, loosely associated conglomeration of tribes… one tribe to a vehicle, always moving mindlessly, instinctively, like sharks – in search of drugs or food or escape from boredom… a normal New Jersey childhood.” Bourdain attempts to find something unique about his childhood in New Jersey and fails to do so. He finally ends his brilliant essay with a small anecdote. On a book tour, he wakes up in an anonymous chain hotel and tries to look out the window for some context as to where he is. What greets him is an “endless and grimly predictable sequence” of stores ranging from Victoria’s Secret to McDonald’s. In his final sentences, Bourdain speculates, “I could’ve been anywhere. I could have been in New Jersey.”