Prominent Figures in Avoiding Stupid, Premature Death

Imagine you are a fourteen year-old in 16th century Paris on a leisurely Sunday – suddenly you trip and roll your ankle down the slippery steps still wet from the rain, gouging your knee on gravel. It’s as if you just got stapled in every part of your body, and your knee is burning and stinging so bad, and tears fill your eyes. As your friends rush down to check if you’re okay, you can bear only one look at it and dread fills you like foul water in a cistern. You’ve heard many stories of kids getting bleeding cuts and getting fevers and some even dying from it. What are you going to do?

We are all humans, and we can all do amazing things in our lives, but if we really take a close look, we are not unstoppable: human lives are much more fragile than you think. It’s astonishing to understand that it took a couple hundred decades to reach this level of knowledge and skill of healing. And throughout this crazy journey of people figuring it all out, there are many prominent figures that have laid the basis of what we now know of the human body and how to treat it.

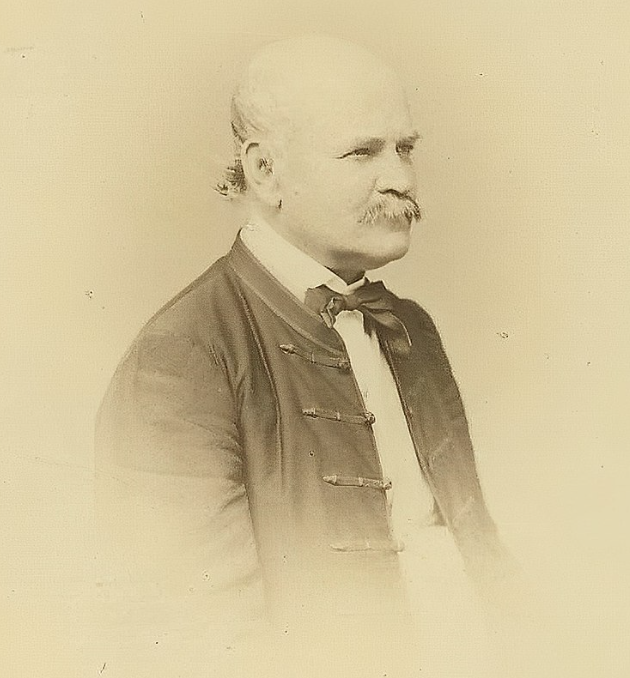

One of the few great innovators in medicine is Ignaz Semmelweis. He was born on July 1, 1818 in Buda, Hungary. At the start, Semmelweis pursued an arts degree at the university at Pest (on the other side of the Danube, where today we have the city Budapest). And then he changed to medical studies in 1837, first in Pest, then to Vienna, Austria. He was the man of his times, for doctors weren’t thinking of illness or disease as an imbalance of bad air or evil spirits. Instead, they looked at the anatomy. Autopsies (detailed medical examination after death) grew common, and doctors got more interested in collecting data. Semmelweis was one of the prime examples of a data-driven physician.

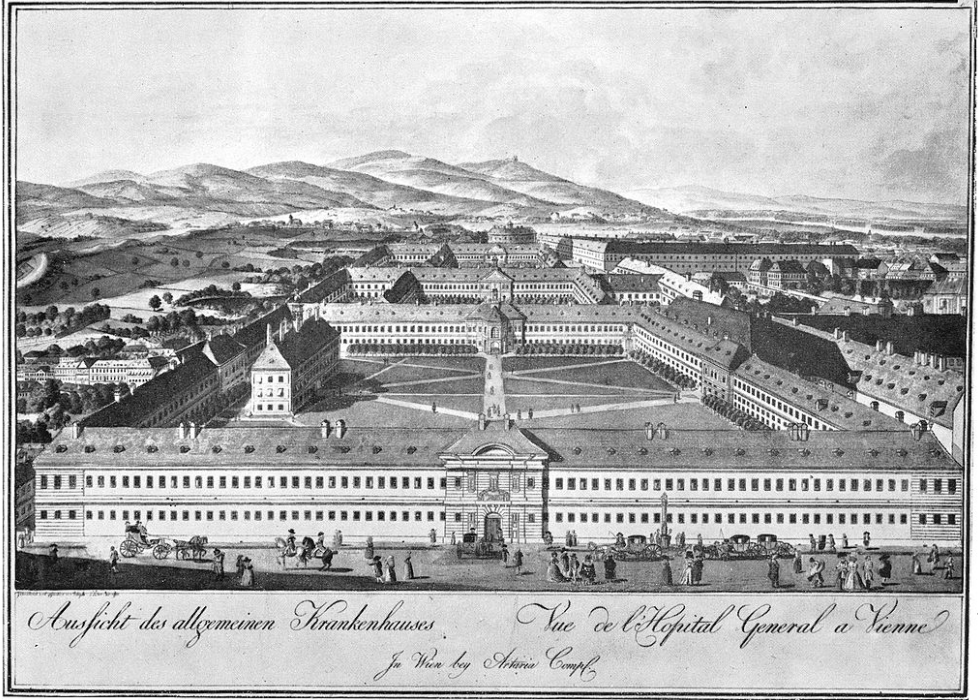

In 1846 Semmelweis began working as an assistant in obstetrics (branch of medicine and surgery related to childbirth and the care of women giving birth) at the Vienna General Hospital, which was one of the largest obstetrics clinics in Europe. He worked with patients and was in charge of supervising the students and medical autopsies. In the clinic, he wanted to figure out why many women were dying of puerperal fever or commonly called “childbed fever”. This bacterial infection of the female reproductive tract occurs during childbirth, miscarriage or abortion. This disease has a high mortality rate, and was also less common among women who gave birth at home.

Semelweis studied two clinics, one with all male doctors and students, and one with female midwives, he counted the number of deaths after, and was shocked to find that the women in the clinic with male doctors and students died at a rate nearly 5 times more than the clinic with female midwives. He started looking through the differences, one was female midwives had women give birth on their sides, male doctors had them give birth on their backs, so he asked the male doctors to try on their sides, and it made no difference. He then noticed that whenever a woman died of childbirth fever a priest would walk through the clinic past the other women’s bed ringing a bell, so he theorized that that scared the other women into falling ill; it made no changes to the deaths when he asked for that to stop. The only difference between the two clinics was the death rates and that the doctors and students wards did deliveries while they also did autopsies on dead women in the next room.

Semmelweis didn’t get a clue about the cause of this disease until he went back to his hospital and found that his colleague, Jakob Kolletschka, a pathologist (diagnose disease by examining organs, body tissues and fluids), had fallen ill and died. It was a common occurrence, according to Jacalyn Duffin who teaches history of medicine at Queens University in Kingston, Ontario. It wasn’t news because this often happens to pathologists, since he pricked his finger with a needle (suffering a scalpel laceration) while he was performing an autopsy on someone and got childbed fever and died. This piece of evidence told Semmelweis that not only women in childbirth can fall ill from childbed fever, but staff and other doctors and nurses in the hospital can also be infected too. Though this didn’t answer Semmelweis’s question, it gave him a clue, and he noticed that in the doctor’s ward they performed autopsies, while in the midwives ward they didn’t. So Semmelweis hypothesized that there were little pieces of corpses or what he called ‘cadaverous particles’ from the doctors and student’s hands when they perform autopsies, so when they delivered babies, these little pieces would get inside the women and cause them to develop the disease and die. So on May 15, 1847, Semmelweis made his staff start cleaning their hands and instruments with not only soap but also chlorine, which is the best disinfectant even today, but while Semmelweis didn’t know anything about germs, he was right, for the rate of death dropped significantly after the doctors and students starting cleaning their hands and instruments.

After this, the mortality rate became comparable between the midwives ward and the doctors’ ward. He found the chlorinated lime solution because he met the housekeeping staff and looked for the strongest product in use at the hospital. Semmelweis chose chlorine because he thought it was the best way to get rid of the smell caused by the little pieces of corpses. His recipe, called the ‘Semmelweis Recipe’, was one part chlorinated lime, and 24 parts water.

In 1848, a woman with cancer in the uterus, who had a purulent discharge was examined. About 12 women who examined the discharge had got childbed fever after and died. Semmelweis concluded that this disease could not only be spread through autopsy material and the opening of skin, but also with other bodily discharges. From then on he recommended hand scrubbing from contact with each patient. We might assume everyone was happy that Semmelweis solved a big problem, but the people weren’t, because it made it look like the doctors were the ones that gave the women the disease. Additionally, Semmelweis didn’t hold back and was brutally honest and straightforward to addressing people who didn’t agree with him, causing him to make some very powerful enemies. “Semmelweis couldn’t find a scientific explanation for his findings, even though his work proved he was right. His published results showed that handwashing reduced mortality to below 1%. While head physician of the obstetric ward of Szent Rokus Hospital in Pest, Hungary, he virtually eliminated childbed fever. Between 1851 and 1855 only 8 patients out of 933 births died from the disease. When a successor took his position, mortality rates immediately jumped sixfold to 6% but physicians said and did nothing” (Board Vitals). His contract wasn’t renewed in March 1849.

So he went back to Budapest and continued his research, but lost his job again. In 1861, Semmelweis finally published his finished work about the cause or origin of childbed fever. But despite that, no one wanted to listen. After years, he got angry and strange, there’s a speculation that he developed a mental condition caused by either syphilis or Alzheimer’s. In 1867 or 1865 (exact date unknown) when he was 47 years old, he had to go to a mental asylum, and he died there either from being beaten and eventually getting sepsis, which he fought so hard to prevent. “The French author and physician, Louis-Ferdinand Céline ended his doctoral dissertation that was dedicated to Semmelweis’ work with the sentence: ‘… it would seem that his discovery exceeded the forces of his genius. It was, perhaps, the root cause of all his misfortunes,’” (National Library of Medicine).

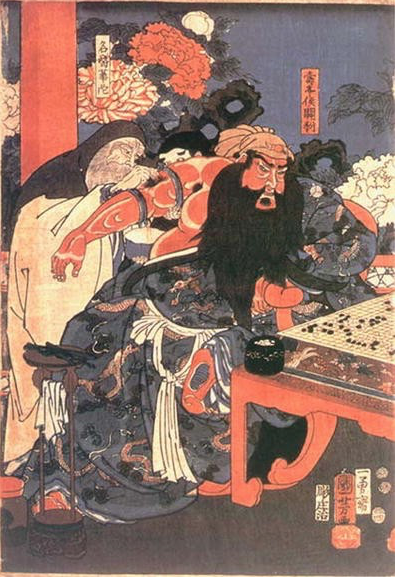

Another prominent figure that’s not so popular here but just as important in other cultures was Hua Tuo.

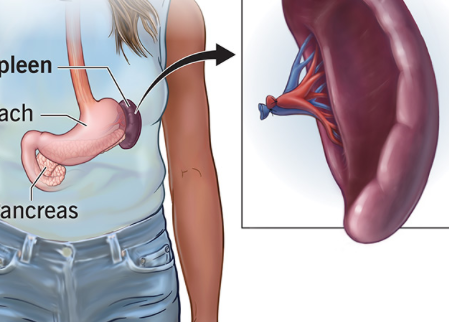

A centenarian, he was born in 108 AD and died in 208 AD. Ancient Chinese doctors saw surgery as a last resort, so little time was spent on experimenting and teaching surgical techniques, and normally surgeries were performed by lower grade medical workers. Hua Tuo hadn’t started his career until the beginning of the 3rd century because as a young man he liked to travel widely and read a lot, so he probably became interested in medicine when he was trying to help countless injured soldiers in that violent period. As a young doctor, Hua Tuo believed in simple prescriptions and acupuncture. Using wine and hemp (a type of cannabis plant), he was able to make his patients insensitive to pain. Hua Tuo is believed to have discovered anesthetics, and he did a wide variety of surgical procedures like: laparotomy (incision into the abdominal cavity), and

removing diseased tissues, and particle splenectomy (removing the spleen).

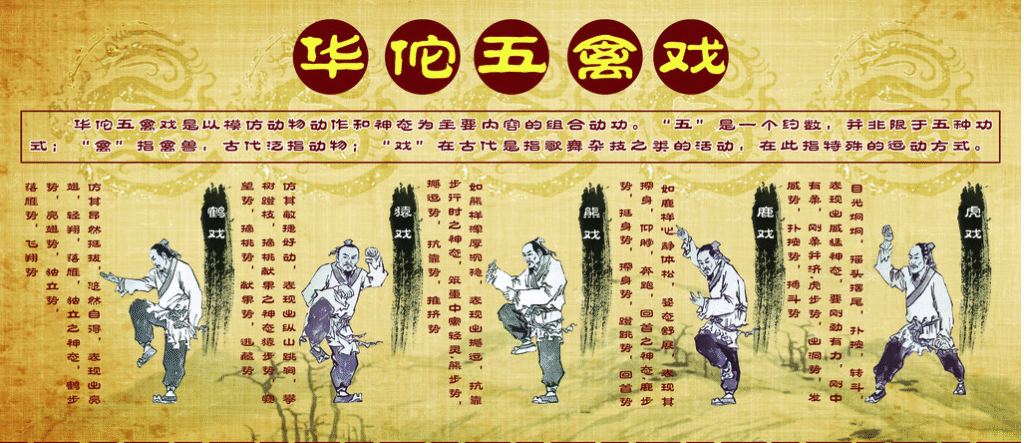

For treating gastrointestinal diseases (any condition or disorder affecting problems in the digestive system) was to resect the viscera (to remove part of or all of an internal organs or organ) and wash the inside. Hua Tuo pioneered (to be one of the first to explore something) in hydrotherapy (water therapy), and physiotherapy (focused on restoring, maintaining and maximizing someone’s range of movement). He’s also the first Chinese surgeon to operate on the abdomen. Additionally, he had a series of movements called the five frolics of animals that were widely known and used where people imitated movements of deer, apes, tigers, bears and birds.

How he died was because of CaoCao, King of Wei, who had strong and terrible headaches, asked Hua Tuo to ease it, so Hua Tuo would use acupuncture to temporarily ease his pain, but CaoCao wanted the annoyance of headaches to be permanently gone, so Hua Tuo informed him that he would need to cut into his royal head as he suspected there to be a tumor inside. CaoCao grew paranoid of that idea and believed that Hua Tuo was trying to kill him, so he ordered him to be executed. It’s unsure whether his major book QingNang Shu, or The Book of the Blue Bag, was ordered to be burned or it was his dying wish for it to be burnt. His impact on medicine was so profound that there are phrases used of someone “being the second Hua Tuo”, or “Hua Tuo reincarcerated”.

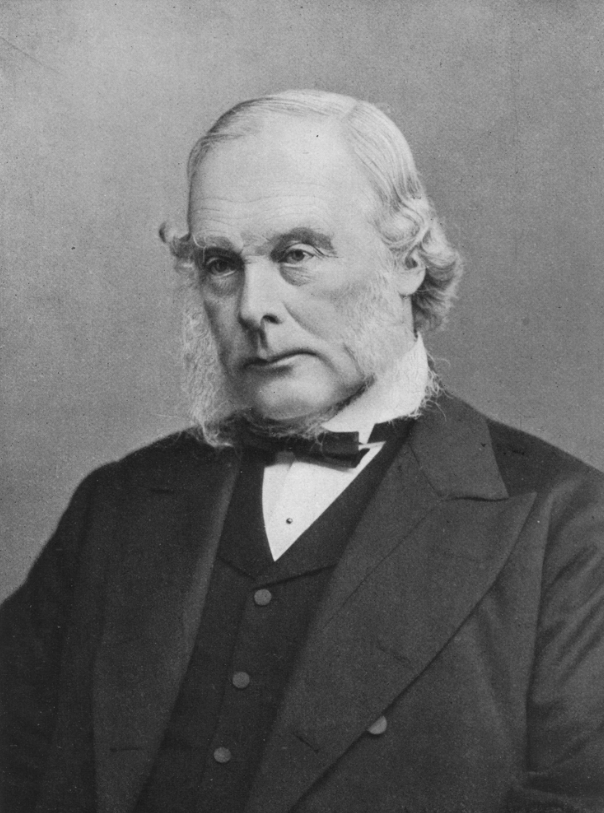

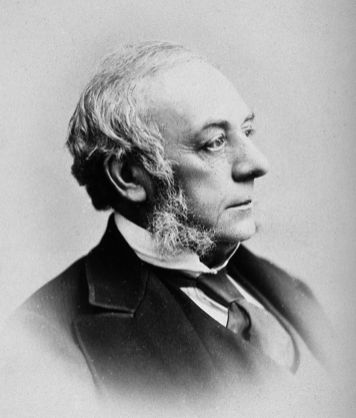

Moving on, we also have Joseph Lister, a British surgeon, and seen as the father of surgery. He was born in Sussex, England, in a Quaker family. In the 19th century, even if an operation was successful, the patient would have still been likely to die from infection. No one knew the cause of the infections and that was the final challenge to make surgery safe. Surgery was still not developed enough when Lister decided to study it in 1844, and Semmelweiss, being in Hungary wasn’t exactly a phone call away (they had barely even begun developing the telegraph at this time). Anesthetics, medications that temporarily reduce pain, were new and allowed surgeons to perform longer and more complicated procedures on patients, but they’d often die after the painless procedure, from the same problem: germs.

Lister’s interest in wound healing started during his first job as a surgical dresser. He accompanied Sir Erichsen during procedures and got to see first hand the signs of bodily infections like decaying flesh, oozing pus and more. Sir Erechson believed that the wounds were infected with miasmas (hazy, unwholesome atmospheres) that came from the wound itself and would get concentrated in the air. Lister was not convinced, because when the wounds were clean, some healed. When he became an experienced surgeon he started using his home laboratory to investigate the infections, and his wife Agnes would help him. He did even more by doing clinical trials at his hospital, making him an exceptional surgeon to others.

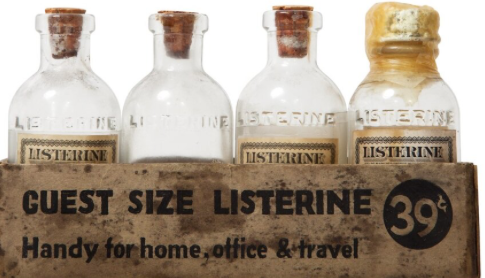

He applied the theory of an antiseptic barrier to the surgery room, and introduced using carbolic acid to wash hands and instruments before surgical procedure, and even utilized a spray for the operating room. He read about the treatment for sewage with a chemical called carbolic acid that reduces disease in cattle grazed sewage-treated fields, so he decided to experiment by washing surgical instruments before the procedure with carbolic acid. He did that in August, 1865, on a seven year old boy’s leg that had a serious leg wound, and no infections were developed and the leg healed in six weeks. After doing this, the rate of infections caused by surgery fell dramatically, so therefore more and more doctors around the world started using this method. Lister even got approval from Queen Victoria to use his carbolic spray before performing a procedure on her. Although Lister made a massive breakthrough, he overlooked sharing credit for his success with other members of the Glasgow team, and he also didn’t support equality of genders in medicine, so Wokesters, beware. Fun fact: Listerine was named after him.

Finally, out of this diverse list of men from different cultures who changed the game, we have flautist Rene Theophile Hyacinthe Laënnec, inventor of the stethoscope.

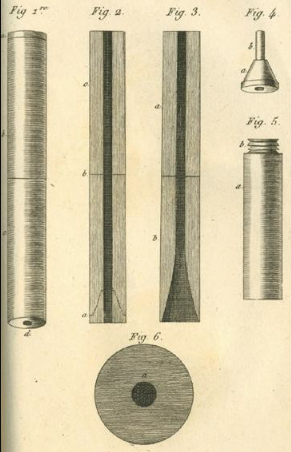

Born on February 17, 1781 and living until August 13, 1826, he used his flute carving skills to make stethoscopes. He had perfected the art of examining the chest cavity through sound processes, like using echoes by bending down his bushy head and plastering his ear against the patient’s chest. Awkward. They say necessity is the mother of invention, and Laënnec was driven by this discomforting retrieval of information. Stethoscopes got rid of the practice of auscultation, where the physician had to place their ear to their patient’s chest to listen. It was the awkwardness of doing this to women that drove his determination to create this instrument. Stethos comes from Greek, meaning chest, and skopein meaning to explore.

When he was only 5 years old, his mother died of tuberculosis, and that left him and his brother under his father’s incompetent care since he was a huge spender, so in 1793, during the French Revolution he went to live with his uncle who was the dean of medicine in the University of Nantes. Under his uncle’s redirection he began his medical studies. In 1795, at the age of 14, Laënnec was already caring for the sick and wounded at the Hôtel Dieu in Nantes. At age 18, he served in the military hospital of Nantes. After the return of the Monarchy in 1816, he got appointed to Necker Hospital in Paris as a physician.

One cool morning in September 1816, Laënnec was taking a walk in the courtyard in the Le Louvre Palace in Paris and he saw two children sending signals through a long hollow wooden tube with a pin. With an ear to one end, the children would use the pin to scratch on one side of the pin, and the child on the other side would hear it through the hollow tube. Laënnec spent 3 years testing different materials to make his tubes, and perfecting his invention. He would use it to listen to his patients’ chests with pneumonia.

Laënnec’s original design of the stethoscope was a wooden hollow tube 3.5 cm in diameter and 25 cm (10 inches) long. It was monaural, meaning not in stereo, as it used a special plug to transmit sound from patient’s chest to a doctor’s ear. His wooden stethoscope was replaced with rubber models in the 19th century, and further advancements like binaural stethoscopes, where it transmitted chest sounds to both ears.

Throughout Laënnec’s medical research, his diagnoses were supported with evidence found during autopsies. Considered as the father of clinical auscultation, he wrote the first descriptions of bronchiectasis (chronic lung condition where airways get widened and damaged, allowing mucus and infections to form), and he classified pulmonary conditions (conditions that affect lungs and respiratory system, making it harder to breathe like pneumonia), pleurisy (inflammation around the double layered membrane surrounding lungs and chest cavity), emphysema (chronic lung condition where air sacs are damaged and enlarged, making it difficult to breathe), pneumothorax (condition where air leaks to the space between the chest wall and lungs), phthisis (bacterial disease that affect lungs) and other lung diseases. He discovered these diseases from the sounds he heard with his invention, and even before that, when his head was pressed up against his patients.

He died at the age of 45 ironically from tuberculosis.