A Journey Through the Familiar: William T. Vollmann’s California

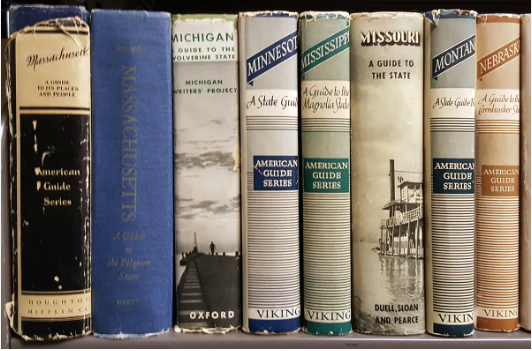

In 2006, Sean Wilsey and Matt Weiland came up with an idea to write a book. It took them two years to pull together a collection of travelogues, detailed narratives, and encapsulating essays. State by State: a Panoramic Portrait of America, was to be a compilation of essays written by an author, carefully handpicked by Wilsey and Weiland, from each state. They wanted to help Americans better understand the rest of their country, without having to live in each state for long enough to fully grasp it. This goal was inspired by an already pre-existing collection of guides published in the 1930s called the WPA American Guide series of the Federal Writers’ Project.

This project, however, produced a lengthy guide for each state. To Wilsey and Weiland, this was obviously too grand for the average American to comb through: learning every minute detail about a state might give you the big picture of it, but it simply would take too long. Instead, they opted for a single book. The introduction to this collection, by Sean Wilsey, is a slow rollercoaster of his trip across America. It is a travelogue of his “long slow drive” from far west Texas to New York in a Chevy Apache pickup so broken down that if he drove it over 45 mph, it would “throw a rod,” or explode.

Wilsey brings the reader through his adventure alongside his dog Charlie Chaplin and his friend Michael Meredith, an architect.

Instead of “rediscovering this monster land” of America like John Steinbeck did in his Travels with Charley, Wilsey’s travels with Charlie (a Catahoula instead of a poodle which was Steinbeck’s dog as well as a different spelling) contained lighthearted moments with his growing friendship with Michael. For example, when being stopped by border patrol agents, Michael and Wilsey figure that they “made no sense as anything other than a gay couple,” which resulted in the agents snickering, which turned to laughter after Michael accidently put the truck in reverse. However, their fun is threatened as the duo’s friendship grows: Michael reveals that he must get back to meet with families in both New York and Washington D.C. because he is a finalist in a competition to design a 9/11 memorial, and some of the zest for this slow experiment fizzles.

Despite the disharmony growing between the men, cramped in the cab of the Apache with a smelly dog sitting between them, there are still ample moments of discovery, like when Don Harris, a “perfectly nondescript” middle-aged man and literary connection in Texas, loads bookworm facts about San Antonio. For example, in a single paragraph, Harris lists a handful of writers, including R. B. Cunningham Grahame, a Scottish lord who “spent several years in San Antonio… beginning his writing career with an account of a hanging in Cotulla for the San Antonio’s Express”,

Stephen Crane who “wandered around with the Chili Queens in the same plaza where the Comanches would ride in receive tribute” and

legislators, like the boxer congressman Henry B. Gonzalez, “who flattened another congressman with a single punch” and even Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was at his office in town on the morning of Pearl Harbor (“I don’t even think he was a general then” he writes). In this storm of references, the reader is almost overwhelmed, but it is important to realize that Wilsey is purposefully doing this: he is bombarding the reader with American culture, echoing both the reason and premise for State by State.

Hastening their journey even further, Michael and Wilsey occupy the truck lane on interstates “needle at 45, sometimes creeping up to 50, steady rain falling”, not saying a single word to each other. Eventually, Wilsey gives up: he couldn’t keep quietly, mindlessly driving–understandably so, who could bear driving at a speedy 45 mph for that long? So, Michael and Wilsey have one final drive together under “cloud-filtered moonlight.” After their separation, Wilsey proceeded to drive for seventeen hours without rest and was finally able to see the New York skyline. Wilsey’s adventure from Texas to New York City was still full of closeups and eccentrics, and even though he failed at his goal of being the “slowest person in America” (because he finished with a 17-hour slog), he still makes it.

Through structuring his introduction as a travelogue that pushes forward–because of Meredith’s deadlines–which also hones in on specific details along the journey, Wilsey gives the reader a preview of what State by State will be like: shifting across the country, from state to state, but also zooming in on the intricacies of each state along the way. Furthermore, by embedding his own travel experiences and feelings into the introduction, Wilsey creates a special connection to the reader and makes his exploration of America feel personal–to experience the trip from Meredith’s eyes would simply not be the same. This connection reflects the whole book too: America is ever-changing, multifaceted, and made up of fifty distinct states, each dynamic and equally important.

William Vollmann begins his essay on California by comparing the heft and breadth of the antecedent (WPA State guides of the 1940s) to the diminutive efforts of Weiland and Wilsey’s State by State: a Panoramic Portrait of America: “allow[ing] each state only a few thousand words” and sarcastically looks to the future by saying that he “dares to hope” that in a few generations from now, the writers assigned to capture the individual state will have an even easier time of it. So this opener is thick with sarcasm, and it sets the reader back a little bit on our heels, for we are here to read about the Golden State, and the writer is insulting the two guys whose idea it is (and who are paying him). But then, the tone can be seen as playful; overall, the reader’s appetite is whetted with a little dash of wry expectation.

The following paragraph is so tiny as to be two transition sentences only (and worth quoting in its entirety): “My home state has met its own losses during this ongoing destruction of differences. Who believes in the ‘California dream anymore?'” The way Vollmann pivots so economically here allows the reader to jump into the study of the state. A vastly more impressive and complex paragraph follows, and we are off, off into Vollmann’s whirlwind presentation of the Golden State, for he has the money from Weiland and Wilsey to fund his flying around the state, as a homegrown tourist. But who is this writer?

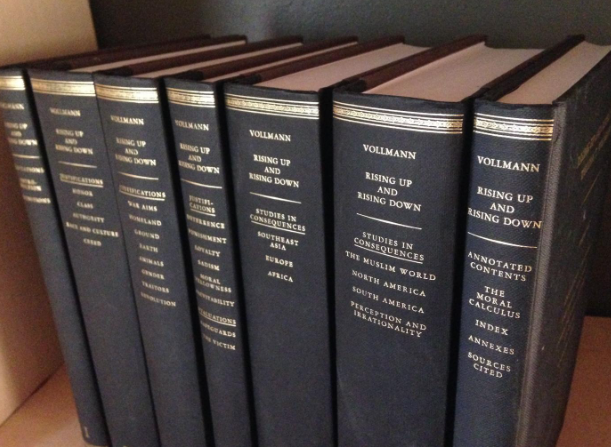

Published in 2003, Rising up and Rising Down, one of Vollman’s more ambitious recent works, is a seven book-long wide ranging study of the justifications and consequences of violence across the globe, spanning different time periods and contexts. The title itself refers to the cyclical nature of violence: the rise and fall of states, empires, governments, etc, and Vollmann ultimately attempts to synthesize a moral calculus for violence from countless places, figures, organizations, and wars. While the premise for this seven book essay is appealing, the execution of it has had mixed reactions. According to an article by Publisher’s Weekly on Rising up and Rising Down, the book fails to “create a style or sensibility that is shocking in and of itself, and that finally holds its unwieldy contents together,” essentially stating that the tome failed to reach its true potential due to the lack of a coherent, impactful writing style that ties it together—one of Vollman’s signature qualities. In fact, that same article elaborates about how Vollmann peaks when he “record[s] impressions of specific, unfamiliar situations and detailing the associations they trigger,” or in other words, his depiction of unusual or intense scenarios. It is clear that Vollmann is a talented writer who is able to picture uncanny, bizarre moments in a way that nobody else can, but after acknowledging his recent failures to recreate that fantastic prose he is known for, it can only be questioned if Vollmann has, in a way, lost his touch?

His view of the state is that it has dirty fingerprints all over it: “…the transformation of the land from a supposedly waste state (you see it had been wasted by Indians, who were rapidly dispossessed, enslaved, or exterminated for the great good) into homesteads”. California was built on the conquest of countless native Americans, who had been on the land for centuries before Americans had gotten their hands on it. Vollmann then adds onto this initial vanquishment of of the state’s natives with a reductive characterization of missionaries who “envisioned it as an empire of saved souls and slave labor”. The forced (violent) removal of these natives was not, supposedly, to hurt them, but to save their souls.

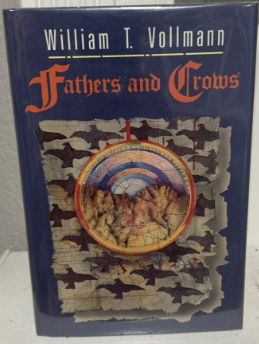

However, keeping in mind that it is Vollman we are reading here, what might seem an accidental or thin mischaracterization of colonial missionaries is not accidental at all. Vollman himself has dedicated thousands of hours of research and writing into a book called Fathers and Crows,

which explores the encounters the Huron and Iroqois had with Jesuit missionaries in Canada before England had taken control. He begins the book displaying the capitalist motives for exploration, later transitioning to the Jesuits’ arrival. Vollmann dives deep into the consequences of the Jesuits actions towards the natives: the war, the famine, and the disease, ironically explaining how the Jesuits insisted that God would save them from smallpox, a disease that they themselves transmitted to natives. While “[Vollmann’s] sympathies are clearly dedicated against the colonizers,” being the Jesuits, he doesn’t display them as monsters. He acknowledges that “they strove to do good, but were they good then?” Really, there’s no easy answer, even for someone who has poured thousands of hours of research and contemplation into it.

After being “seized by the United States,” California began to “incarnate a dream of gold.” Vollmann sets the reader all the way back to the beginning of the state, just so the reader can fully understand how deeply rooted the “Californian Dream” (to make it big) really is. After his introduction of the dream, he moves on to the evolution of it: the different ways this idolized dream of getting rich emerged in the state. From the “gorgeous golden infection” of growing citrus to an “[addiction] to irrigation,” Vollmann highlights how golden the Golden State was envisioned to be; it was a “sunshiny paradise.” But, in typical Vollmann style, he flips everything in a complete 180° to shock the reader. California, and its signature dream, became a “nightmare parody.” Everything golden about the state quickly turned into a particularly poignant shade of disgusting brown: “homesteads became corporate farms; highways crawled with cars; city air turned brown…urban ghettos stuck out like sores.” According to Vollmann himself, California now is “the land of long commutes, unaffordable homes, Superfund toxic waste sites, overburdened public services, bad schools (except for the rich), increasing crime–in short, the land of reality.” How can we not agree with Vollmann when he says “who believes in the ‘Californian Dream’ anymore?” after being smashed with the harsh reality of the golden state.

Beginning his next transition paragraph (or mini-paragraph) with “all the same”, we see that Vollmann’s sense of humor is flowing – for he self-deprecates by admitting that he himself is a “subspecies of my own general sort of life form occupying interesting niches”; this follows his reporting the good news that California boasts the widest array of species in the nation.

Finally, Vollmann takes the time to set his identity firmly in the California we all know about but maybe don’t know, and he holds a mirror up to those from back East. In this mirror holding, he draws a line between himself (and all Californians) and those from “history-stained” towns, like Boston, Providence, Salem, Rochester”. He uses the word “alien” which is a synonym to “foreign” but the latter wouldn’t work in an essay about national identity, and what are these cities’ qualities that are alien to the Californian Vollmann? “Winters, rains and ancient violence,” he says, “blotch the[…] walls” of these old cities in the East, and Vollmann prefers the Californian “unassuming informality… or […] blasé anonymity (who cares if that woman is sticking her tongue into another woman’s mouth?)”. What we have here, at the final paragraph of his introduction is a hint of things to come: he’s going to “drive-through” (or fly through) the state as a hedonistic explorer, exposing us to a shocking array of sights, some beautiful, some R rated, all while keeping a tone of tolerant indifference.

Vollmann begins his “drive-through” not with the famous cities of Los Angeles or San Francisco, which envelop the Californian dream, but with a “certain Californian creek […] a green secret, rich in willows and tamarisks through which one must fight to see the white-foamed brown water spilling through the tender grass.” However, Vollmann contrasts this with the secret creek’s location, an “unassuming G-string of green in a rocky gully.” Vollmann performs another complete flip, circling back to “104,000 irrigated acres of Palo Verde,” which “have made green fields out of the Colorado River’s western shore.” Here, in the beginning of his exploration of California, Vollmann is familiarizing the reader with the turbulent, constantly shifting nature of the state. In one instance, one might relax in a lush, green creek, but just five steps away lies a completely different climate: you never fully know what to expect in California.

He seems to ring the oft-rung climate change bell now, bemoaning the drained marshes, the polluted lakes, etc, and hearkens back to the mid-20th century when luscious fruits like melons and grapefruits were hemorrhaging from the state in great numbers, and ends this section by invoking Steinbeck’s agri-centric prose.

But he can’t seem to restrain his being a high literary artist, exerting this flair when he references an obscure Japanese novelist named Mishima, stating obtusely, “just as Mishima’s Sea of Fertility was named after an airless wasteland on the moon, so California’s abundance often appears in a disturbing arid perspective, should one only take a few steps back”. However, this does sort of perfectly fit the previous statement about the creek, where he takes “five steps back”. Is that what he is doing in this essay? Trying to take a few steps away from the California he knows so as to get a perspective which is at least a little bit more journalistic?

The next section is puzzling, but worth looking closely at. Vollman seems to go through a cycle, first starting with a detailed paragraph about the intricate architecture of a single building in downtown LA. It’s almost as if he has strapped the reader onto a bird that cinematically glides through this building. First, we descend from a “winding staircase,” following gracefully swiveling water down “a canyon of skyscrapers, trees, and shrubs, ending in a fountain,” then, we end up at the destination, the cafe; however, we don’t forget to take a look in the upside-down reflection of the water, seeing the soaring Citigroup Building. After this paragraph, Vollmann describes different buildings, taking an overhead perspective. Now he zooms in on Pico Blvd, a famous street full of food. In all of its “six-lane wideness,” Pico Boulevard is filled to the brim with different markets and restaurants that stretch all the way down to the coast. Yet, Vollmann undermines the vastness of Pico Boulevard by only mentioning one place, The Eliass Kosher Market. Countless restaurants and bodegas line the streets of the boulevard, each with distinguishable, different tastes, and you don’t have to take my word for it: famous food critic Jonathan Gold

attempted to eat at every restaurant on the boulevard in one year and “never made it to the beach.” However, Gold himself admits that despite its richness, Pico is unknown, “left alone like old lawn furniture moldering away in the side yard of a suburban house.” So, instead of undermining the diverse food street that is Pico Boulevard by not mentioning the plethora of restaurants there, perhaps Vollmann is commenting on the lack of recognition for the street by playing into the general sentiment of overlooking the street, since everything Vollmann does is on purpose.

Suddenly he jumps far away to… Owens Valley, mentioning “white abrasions” or “grayish-green fields…bluish-green veins of trees…[and] rich brown windings of Owens Creek [that] became Owens River, then Owens Lake.” It is “pastel with dust, snow, and clouds”. Yet his final paragraph in this section circles back to architecture once again, obsessing over “Spanish curvy red roof tiles” or “elaborate metal work.” However, one might ask, why? Why did Vollman take us from one of the most bustling food ecosystems on Pico Boulevard to some valley over a hundred miles away? At first glance, there seems to be absolutely no reason for it. However, after close research of Vollmann himself, it can be discovered that he actually went to college in California at Deep Springs College, which is located over forty miles away over a few mountains from Owens Valley. He is secretly inserting some of his own experiences right under the reader’s noses. For the most part, he has been driving the reader through the state like a tourist: showing off different significant parts; however, at this moment Vollmann is including a stop on the trip not because of its importance to the State, but because of its importance to himself. He does this without anybody knowing; he makes Owens Valley appear as though he has no connection to it, that it is in fact just another stop on our trip through California. Vollman’s secrecy in including Owens Valley is an example of his subtlety: we are again unknowingly viewing California mainly through his past experiences.

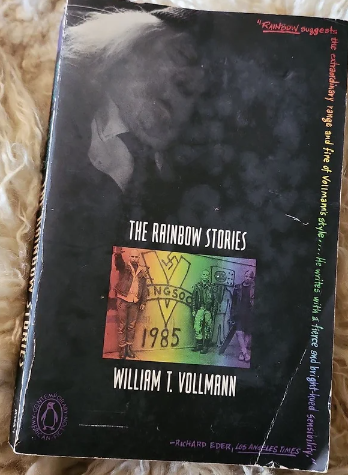

To truly understand how Vollmann tours through the familiar, one must examine a section of the essay set in San Francisco. In “California,” Vollmann explores a “certain S&M club and dungeon” which displayed “the most effective ways to inflict fear and spicy physical stimulation…employing hot and sharp objects as needed,” (Vollmann 52). Vollmann then provides the reader with an intimate and intense journey through his experience at this club, including details far too profane for anyone’s comfort. Unsurprisingly, Vollmann is familiar with this aspect of California.

His “Rainbow Stories” document the bizarre in a series of color-themed stories. Whether it be the San Francisco skinheads in “White Knights,” or prostitutes in “Ladies and the Red Lights,” Vollmann has seen and written about it all. He has once again cunningly brought the reader through a world he seems to be all too familiar with, right under our noses.

Student Feedback for Michael’s effort by Taylen Li and Simon Lim:

Michael, your essay was an excellent account and deciphering of Vollmann’s California, which I found to be the most complex chapter in Weiland and Wilsey’s State by State that I have read so far. Your introduction was certainly one of my favorite parts of the essay. By referring to the Introduction as a “travelogue”, you guide the reader through the intro of State by State, and from there, you transition smoothly into Vollman’s California. Something I noticed was that throughout your essay, you not only talk about the chapter, but also about Vollman himself. For instance, you go into great detail about his book, Rising up and Rising Down, in which you explain a lack of the author’s signature writing style in depicting bizarre scenarios. Although I’m unsure what your purpose was in adding that particular segment, you do draw some attention to Vollman’s supposed fall from grace, and the audience is given somewhat of a warning about the ensuing contents of the chapter. You also talk about Vollman’s research on the Jesuit missionaries’ misdeeds against the Huron and Iroquois natives in creating Fathers and Crows, and altogether, these small diversions from the central topic assist the reader in gaining a finer understanding of Vollman as a writer and person. At first the title of your essay, “A Journey Through the Familiar: William T. Vollmann’s California”, seemed to confuse me. However, after some deeper analysis, I found that throughout the narrative, you hint at very personal connections and experiences that Vollmann has with his state. You discover that Vollmann’s sudden jump to talking about Owens Valley is possibly associated with his time at Deep Springs College, around a one hour drive away, and not only that, but later you also find that Vollmann’s depiction of the S&M club has to do with his familiarity with that particular aspect of the streets, as he also wrote the “Rainbow Stories” documenting the prostitutes and skinheads of the Tenderloin District. So in naming your essay “A Journey Through the Familiar”, you portray Vollmann as a tour guide who, in informing readers about his home state, also follows a journey through his past experiences, and while doing so, makes no attempt to share the full breadth of those experiences.

I found your analogy of Vollmann’s perspective on California to be remarkable; a state covered in “dirty fingerprints”. This transitions very well into the subsequent depiction of California’s history – from being acquired by the United States in hopes of obtaining a utopia for gold to its more modern state of harboring crowded highways and urban ghettos. All in all, your essay was a very well-written weaving together of Vollman’s personal journey through the state of California, as well as the underlying purpose of “State of State”.

Michael Lin,

Great job with this essay. I really like the way you engaged with Wilsey and Vollmann’s works. Your writing shows a solid understanding of both authors’ styles and perspectives, and your use of direct quotes was truly effective in grounding your analysis.

For example, when you describe Wilsey’s journey as “a travelogue of his ‘long slow drive’ from far west Texas to New York in a Chevy Apache pickup so broken down that if he drove it over 45 mph, it would ‘throw a rod,’ or explode,” you really capture the slow, uncertain, and precarious nature of Wilsey’s trip. This quote really helps to convey the mood and tone of Wilsey’s narrative, giving the reader a vivid picture of both the physical and emotional landscape he’s navigating himself through.

I also found your analysis of Vollmann’s introduction very insightful. You highlight how Vollmann “dares to hope” that future writers won’t have to go through the same struggles, which you interpret as a sarcastic tone that immediately perks the reader’s ears. This is compelling because it spots Vollmann’s ethos – his authority as a writer who has “thousands of hours of research and writing” invested in his work. By quoting this you demonstrate how Vollmann himself is an expert who has seriously engaged with his subject, adding weight to his voice.

One thing you pointed out in your writing is how Vollmann takes on the role of a tourist in his own state, discovering details and fresh perspectives. But at the same time, as you pointed out, he also leads us through places that are already familiar to him – like maybe his visit to the S&M club in San Francisco – blending the new with the known. Earlier you mention that his seemingly reductive remark about the Jesuits is actually backed-up by the fact that he’s written extensively on the subject (specifically in Fathers and Crows). This goes back to your point that Vollmann is effectively playing with the idea of authority (his implicitly-earned right to speak freely) or expertise (his chops as a literary figure who covers gutter topics and war zones).

Overall, your essay is well-structured and thoughtful, and your use of quotes is especially strong. You clearly know the texts well and have formed a nuanced opinion on the authors’ works. Again, great job with this essay. It definitely pumped me up to start my own State by State writing.

Michael, your essay was an excellent account and deciphering of Vollmann’s California, which I found to be the most complex chapter in Weiland and Wilsey’s State by State that I have read so far. Your introduction was certainly one of my favorite parts of the essay. By referring to the Introduction as a “travelogue”, you guide the reader through the intro of State by State, and from there, you transition smoothly into Vollman’s California. Something I noticed was that throughout your essay, you not only talk about the chapter, but also about Vollman himself. For instance, you go into great detail about his book, Rising up and Rising Down, in which you explain a lack of the author’s signature writing style in depicting bizarre scenarios. Although I’m unsure what your purpose was in adding that particular segment, you do draw some attention to Vollman’s supposed fall from grace, and the audience is given somewhat of a warning about the ensuing contents of the chapter. You also talk about Vollman’s research on the Jesuit missionaries’ misdeeds against the Huron and Iroquois natives in creating Fathers and Crows, and altogether, these small diversions from the central topic assist the reader in gaining a finer understanding of Vollman as a writer and person. At first the title of your essay, “A Journey Through the Familiar: William T. Vollmann’s California”, seemed to confuse me. However, after some deeper analysis, I found that throughout the narrative, you hint at very personal connections and experiences that Vollmann has with his state. You discover that Vollmann’s sudden jump to talking about Owens Valley is possibly associated with his time at Deep Springs College, around a one hour drive away, and not only that, but later you also find that Vollmann’s depiction of the S&M club has to do with his familiarity with that particular aspect of the streets, as he also wrote the “Rainbow Stories” documenting the prostitutes and skinheads of the Tenderloin District. So in naming your essay “A Journey Through the Familiar”, you portray Vollmann as a tour guide who, in informing readers about his home state, also follows a journey through his past experiences, and while doing so, makes no attempt to share the full breadth of those experiences.

I found your analogy of Vollmann’s perspective on California to be remarkable; a state covered in “dirty fingerprints”. This transitions very well into the subsequent depiction of California’s history – from being acquired by the United States in hopes of obtaining a utopia for gold to its more modern state of harboring crowded highways and urban ghettos. All in all, your essay was a very well-written weaving together of Vollman’s personal journey through the state of California, as well as the underlying purpose of “State of State”.