Two portraits of the scum of the earth: Guy de Maupassant’s ability to portray criminal effectiveness.

Guy de Maupassant lived only 43 years (1850-1893), but his impact in fiction is such that almost any great writer is consciously or unconsciously influenced by this father of the modern short story. Maupassant’s childhood was not without drama; he was raised in a single parent family after Laure Le Poittevin,

the mother, obtained legal separation from her violent husband. This was far less common than today, and she risked social disgrace for her acts. And as a member of minor nobility (denoted by the “de” in Maupassant’s full name) many eyes were on the family. In 1870 the Franco-Prussian War broke out and Maupassant quickly volunteered for the French Army. This proved a major moment in his life; the majority of his early works were tales from the war.

Guy de Maupassant’s short stories are incredible in their own right, and 1880 marks the publishing of his first masterpiece, “Boule de Suif”. This truly kicked off his career in writing and the years to follow would be his most fruitful in terms of volume published. This talent and success brought him wealth and with it, a plethora of vices which slowly worked away at him.

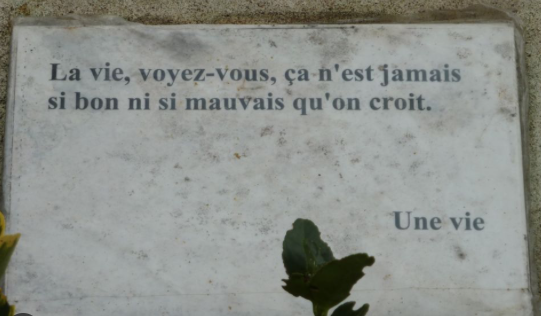

Nearing the end of his life he yearned for solitude and his mental health continued to devolve until eventually in 1892 he attempted to cut his own throat. He was sentenced to a private asylum where he spent his last months, dying in 1893 from syphilis. Maupassant made his own epitaph (writing on a gravestone) stating: “I have coveted everything and taken pleasure in nothing”.

The fear that haunted his restless brain day and night was already visible in his eyes, I for one considered him then as a doomed man. I knew that the subtle poison of his own “Boule de Suif” had already begun its work of destruction in this magnificent brain. Did he know it himself? I often thought he did. The MS. of his Sur L’Eau was lying on the table between us; he had just read me a few chapters, the best thing he had ever written I thought. He was still producing with feverish haste one masterpiece after another, slashing his excited brain with champagne, ether and drugs of all sorts. Woman after woman in endless succession hastened the destruction, women recruited from all quarters… actresses, ballet-dancers, midinettes, grisettes, common prostitutes– ‘le taureau triste’ his friends used to call him.

• Munthe, Axel (1962). The story of San Michele. John Murray. p. 201.

“The Donkey” (1883, from a collection of short stories entitled Tales of Trickery and Deception) revolves around two characters and the shenanigans they get themselves into. We see them jolly, enjoying themselves, despite or perhaps because of the horrendous acts they are committing. We see them purchase a donkey from a woman and shoot it right in front of her, not quickly and mercifully, but slowly, dragging it out as long as possible for their own entertainment. And once the donkey is dead, they go sell the donkey for a profit by means of deception.

Maupassant, a boatman himself, and a writer with extreme sensitivity to nature, opens the action when “day […] was breaking and the hill was becoming visible. In the dawning light of day the plaster houses began to appear like white spots”. The location is on the River Seine, outside of Paris, by a town named Frette, running through the royal hunting grounds.

Maupassant sets forth the action by first establishing a peaceful setting to be penetrated by evil, setting the stage for his two main characters to come along. The way he frames his stories is always distinct. For example, his story “At Sea” begins with an article in the papers, “My Uncle Jules” begins with an unknown character (presumably Maupassant himself) donating a few francs to a beggar, and “A Ghost” begins with an old man telling his story for the first time after keeping it secret for over 50 years.

“Sometimes whispered words, coming perhaps from a distance, perhaps from quite near, pierced through these opaque mists”: with these depictions he paints a scene of tranquillity, but as soon as criminals get involved it breaks the tranquillity with chaotic action. The events that transpire so soon after this calm introduction are so jarring that the reader is left feeling disturbed. The contrast between the imagery and behavior gives the feeling of nature being set off balance by depraved humanity.

Within the story of “The Donkey” there appears to be an odd dynamic between the two characters, Mailloche and Chicot. They have an uncanny way to perfectly even each other out for criminal success. And this can even be seen in their appearances: one is tall, one is short, one is slim, one is large – but less noticeably, their attitudes dovetail. Chicot is consistently more cruel and conniving, while Mailloche tends to simply listen and obey.

Perhaps something about their odd pairing is what leads to their ability in upending business transactions to their benefit. Chicot has an innate ability in disarming people: most noticeably would be his tendency to call everyone, regardless of gender, “sister”. This does a combination of things. It gives the interactions an unserious air, and it works on the reader to give them a sense of playfulness in the air, when what is occurring is actually quite cruel. This emphasizes the reader’s growing nausea and increases the strong sense of lingering irony throughout the story. Mailloche is described to have “the restless eye of people who are worried by legitimate troubles and of hunted animals”, which is a very interesting trait for Maupassant to mention. A crook, who operates below the civil threshold, is both a hunted animal and a person with legitimate problems, since they work in opposition with society’s standards. So in one sense the criminal must not only stay on their toes, being cunning and calculating, but must also be instinctual. This combination of skills is engaging, and requires a crafty persona. So, in another sense the criminal must be savvy as he or she continues their rampage, savvy and smart. But this combination is destructive; while entertaining for the criminal, providing him or her with any number of thrills, it acts as a poison on society. As the criminal entertains himself, he leaves a trail of mayhem behind.

In this story Maupassant makes the donkey’s inherent worthlessness quite clear from the start. Even the owner states: “I’m going to Macquart, at Champioux, to have him killed. He’s worthless”. But nevertheless, Chicot purchases the useless thing for five francs. For a beggar, or a poor person, five francs in the 1870s (or earlier) is not something to look down upon; we later see the pair sell two rabbits for a grand total of 2 francs, 65 centimes (under $10 in today’s dollars). Now why would they buy a worthless donkey for such a price? This question is answered by Chicot’s simple yet ominous statement, “[We] want to have some fun”. It’s off-putting and appropriately so – they go on to torture and kill the poor beast. Their cunning, which is offset and empowered by their endless pursuit of mirth, enables them to find such value, and therefore success, in a worthless thing, but the value doesn’t stop there. They go on and fool a dealer into buying the corpse of this worthless animal for 20 whole francs – passing it off as a deer!

The story’s last line: “And he disappeared in the darkness. Maillochon, who was following him, kept punching him in the back to express his joy”.

If we take “The Donkey” as an examination of how criminality is associated with profits, excitement, and sadism, then “My Uncle Jules” is a story which reveals how bombast and overconfidence can create unrealistic expectations, which leave a trail of sorrow in its wake. Both stories are intriguing when one considers the resulting punishments. For in both stories Maupassant lets them off scott-free, without any retribution for the dismay they have caused.

“My Uncle Jules” is rife with examples of deepening irony and festering delusions, from the father’s false hope to Jules’ overconfidence and ease of lying, to the coldhearted reality of the resolution. We hear the story of a man (Jules), who goes off to America alone, taking more than his share of the family’s accumulated wealth to prospect for riches. However, he redeems himself by sending a message stating his unwavering health and conviction to right his wrong and bring back fortune to his home. Jules and his promise becomes the singular hope for the family, and they wait day by day for his return.

What makes Jules such an effective scoundrel is his technique of leading people into a fallacy of his own creation. With only a couple of hand-written letters he instills the feeling of hope in his family. He gives them a glimpse into a future of riches and success, which Jules knows they desire deeply. However, there is a fine line between hope and delusion, and this family has long since crossed that line; Maupassant makes this clear. His narrator’s statement, “This letter became the gospel of the family. It was read on the slightest provocation, and it was shown to everybody” gives the reader an idea of how deep this deception has spiraled. For a Christian family, the gospel is something to be cherished and admired, but in their case, they are not worshipping God; instead, they are idolizing Uncle Jules and the profit he promises. We can see their desire for money even more clearly in the way they walk to church. Maupassant describes them as, “arm in arm. The [daughters] were of marriageable age and had to be displayed”. It’s obvious that reverence towards God is not on their minds, but instead the chance for social and economic advancement is.

“My dear Philippe, I am writing to tell you not to worry about my health, which is excellent. Business is good. I leave to-morrow for a long trip to South America. I may be away for several years without sending you any news. If I shouldn’t write, don’t worry. When my fortune is made I shall return to Havre. I hope that it will not be too long and that we shall all live happily together.”

One of the key components in manipulating hope in others is the use of confidence. It can be seen that Jules has mastered this, as there isn’t a speck of doubt in his words when he says he will be successful. Confidence oozes from his sentences; he doesn’t bother with if or maybe, but just uses concrete statements that he will make his fortune and he will restore his name. It brings into question, what is the difference between overconfidence and lying? Did Jules predict how his overwhelming surety would root itself into the very values of his family? And why did he do it?

Like a game of Jenga that’s been going for too long, the lie eventually comes crashing down. On a celebratory trip to Jersey the family boards a steamboat and watches as the coast slowly disappears. An old ragged sailor sits, opening oysters with a knife, and handing them to a pair of gentlemen who in turn offer them to their ladies. The father is intrigued by the delicate method of these women eating and decides to show his two daughters how to eat in a similar manner. Once they approach, the father recognizes the ragged sailor as his brother Jules, the man that’s supposed to be off in America making a fortune. The cold-hearted reality and truth comes rushing in, and the realization leaves the father stunned. Maupassant drives his point home with the very last line: “But as no one was eating any more oysters, he had disappeared, having probably gone below to the dirty hold which was the home of the poor wretch.”