The Life and Work of Robert Capa

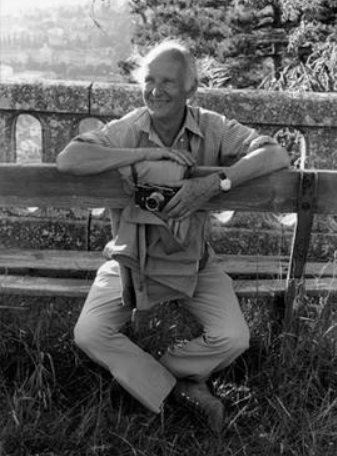

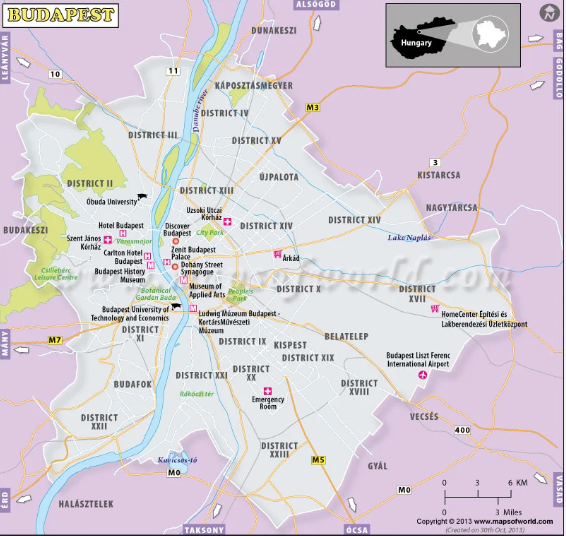

Robert Capa (1913-1954) was one of the greatest photographers and photojournalists of the 20th century and arguably the most monumental war photographer in history. Capa was born in Budapest, Hungary, as Endre Ernő Friedmann to the Jewish family of Julia and Dezső Friedmann. As a child, Capa was involved in a kids’ gang that wandered about the Jewish quarter of Pest, Hungary. His aggressive attitude was rewarded with the childhood nickname of Capa, which translates to Shark in English. Within the group of boys, Capa was known to be fearless, and one to always be seeking adventure.

In his early life, Capa became involved with leftist revolutionaries and controversial politics. Despite never actually joining the Communist Party, when the youth was just eighteen, he was accused of apparent communist sympathies. At a Budapest demonstration against the Hungarian fascist dictator Miklos Horty, Capa (at the time Andre Friedmann) was wounded and arrested by policemen. He was forced to flee Hungary for his safety and moved to Berlin. Initially, Capa had wanted to become a writer and journalist, but since his fluency in German was still significantly faulty, Capa became a photographer, as it was the nearest thing to journalism that didn’t require a spoken language. After finding work as a photographer in Berlin, he fell in love with the art of recording images. Capa had a new goal in mind, and that was to combat fascism with photography.

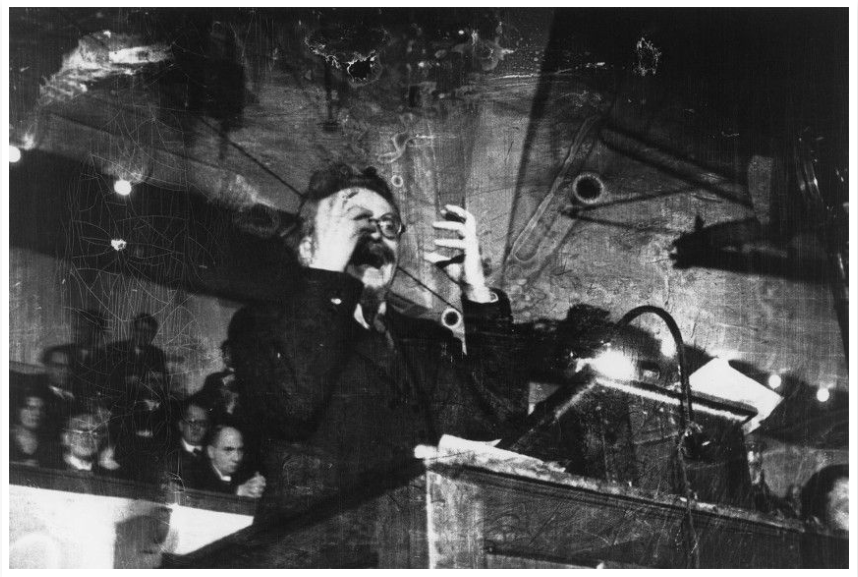

In 1930, Capa enrolled in journalism classes at a radical school for political studies, known as Deutsche Hochschule für Politik (German Academy for Politics). Upon finishing school, Capa worked in Dutch-Hungarian photographer Eva Besnyo’s darkroom for a year until an opportunity arose – Soviet exile Leon Trotsky was to speak in Copenhagen and Capa wanted to photograph it. “The Meaning of the Russian Revolution” was Capa’s first photograph, and through a brilliant employment of lighting and shadow, a stunning depiction of the passionate Leon Trotsky was captured.

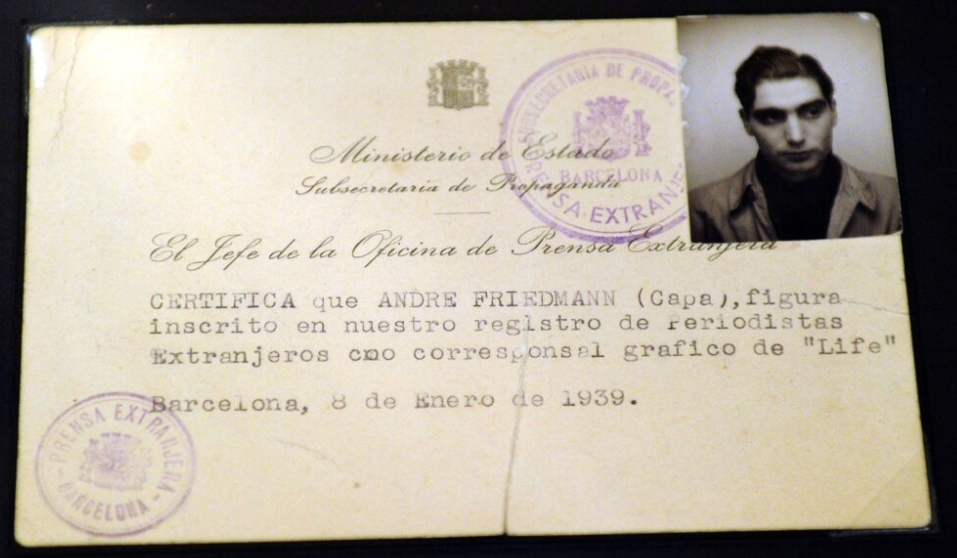

After witnessing the rise of the Nazis and their ruthless persecution of the Jews, Capa felt unsafe as a leftist Jew living in 1930s Germany and decided to move from Berlin to Paris in 1933 with his camera and not much else. There, the impoverished man changed his publishing identity to Robert Capa, a more Americanized name, to avoid discrimination in France – thus making it easier to find work as a freelance photographer. His photos began to sell so successfully under the fabricated pseudonym that the man decided to officially change his name to Capa.

In Paris, a 20th-century site of artistic freedom and expression, Capa met the love of his life, Gerda Taro, who had just gotten out of prison on a charge of anti-Nazist propaganda. Gerda was a German photographer who had fled Nazi Germany for the same reasons as Capa, for she too was a Jewish refugee that narrowly escaped persecution. A friendship was established at first, but the two grew closer together through their work and collective passion of photography. By the summer of 1935, Capa captured the vivacious woman’s heart and presented her with her first Leica as a gift.

In the cafes of Montparnasse, Capa met a group of fellow refugees from Germany and became friends with Polish photographer David Seymour,

(nicknamed Chim) and French artist Henri Cartier-Bresson. The three were collectively known as “the Three Musketeers”. Capa, Seymour, and Cartier-Bresson worked together using 35mm cameras and captured political drama unfolding in the streets of Paris. In particular, the group photographed the demonstrations of the leftist Popular Front coalition that campaigned for better working conditions against the fascist leagues. For Capa, taking photos was his way of fighting the war against fascism – instead of a gun, he carried a camera.

At the spark of the Spanish Civil War, Capa and Taro hurried off to Spain to capture photos of the war. Taro herself had wanted to reveal the suffering of the civilians and soldiers as a result of the war. Her various photographs depicted brave soldiers, struggling families, and the emotional power that she possessed with her camera in hand. Meanwhile, Capa photographed the experiences of the common people during the war, and they were published in magazines around the world. The couple camped with the soldiers, risking their lives many times to cover the fighting up close while capturing everyday life with their cameras.

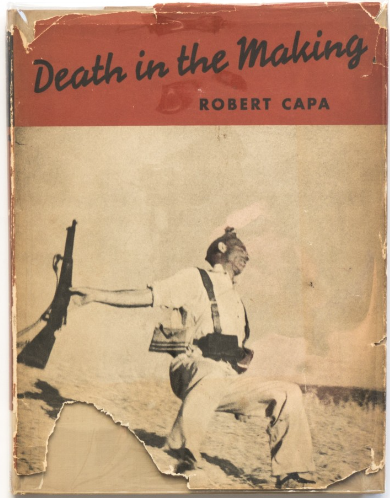

One Sunday on the 25th of July 1937, tragedy struck. During a retreat of the Republican Army at Brunete, a town west of Madrid, Gerda Taro was hit by a tank and died the following day. She was only twenty-six, and the incident left Capa heartbroken for the rest of his life. One year after the death of his beloved Gerda, Capa published a photo book, Death in the Making, to memorialize the photos they had taken together and commemorate his life partner.

Taro would go down to be remembered as the first female photographer to be on the front line and die during the war. Despite the couple never getting married, Capa called Gerda the woman of his life. The story of Robert Capa and Gerda Taro, two lovers who died for freedom, while doing what they had loved, has inspired many.

The book Death in the Making contains photos that illustrate the early days of the war, covering the lives of both soldiers and civilians, as well as men and women. The beginning of Death in the Making portrays the initial excitement and innocent alacrity of soldiers departing from home and the journey they make as they prepare for the battlefield. The Republican soldiers are seen playing with animals, smiling and cheering on the train to the Aragon front, and listening to inspirational speeches from commanding officers. However, as the book goes on, the darker parts of war come into view. Capa reveals impoverished commoners, civilian victims running for their lives, men carrying their dead comrades, and soldiers in buildings and schools, preparing to fire. One scene taken by Capa from an elevated place depicts a speech being held, which very much resembles that of the Saint Crispian’s Day Speech from old Shakespeare’s Henry V.

Without a doubt, Capa’s most iconic group of captures are his “Magnificent Eleven” photos of D-Day. These celebrated negatives are characterized by the landings of American troops on Omaha Beach, France. Some portray soldiers trudging knee-deep in water whilst carrying loaded backpacks, buckets, or even their fallen brethren. Along with the soldiers, they are accompanied by partly-submerged tanks, immersed artillery, and Czech hedgehogs, which were large metal x-shaped obstacles that were used to block off enemy tanks. In most of these D-Day photos, a similar backdrop of the looming beachhead is visible in the background. As for the foregrounds, they are distinguished by the detailed seawater, sweeping waves, and swooshing sea foam.

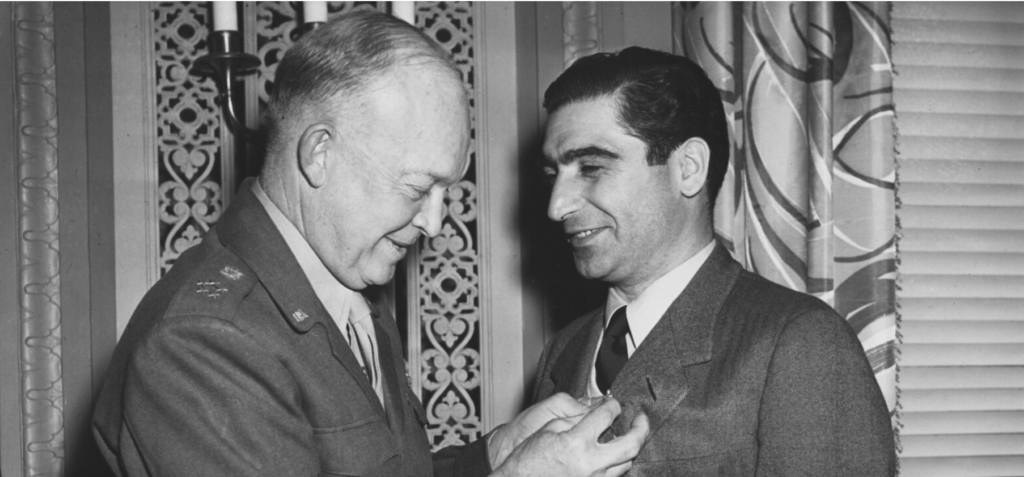

In 1947, Capa was awarded the Medal of Freedom by U.S. General and later President, Dwight D. Eisenhower. That year, Capa also co-founded Magnum Photos in Paris, the first collaborative agency for worldwide freelance photographers that served to provide pictures for international publications. He became president of the organization and was responsible for managing work for freelancers.

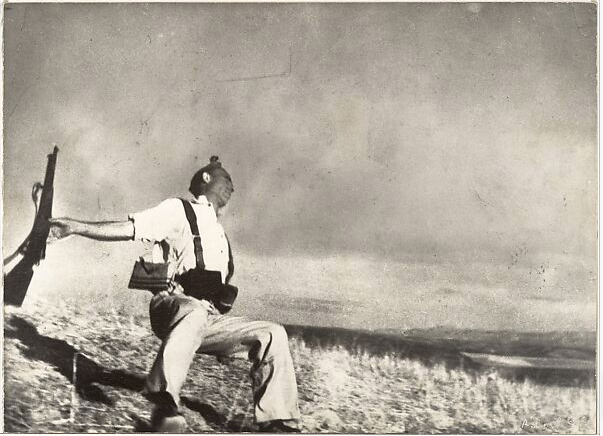

Along with documenting World War II across Europe, Capa also covered and published photos of five wars in ten different countries, including the Spanish Civil War, the Second Sino-Japanese War, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, and the First Indochina War. Capa’s most famous photo, “The Falling Soldier”, was taken during the Spanish Civil War; it depicts a poignant black-and-white image of the death of anarchist militiaman Federico Garcia as he falls backward from being shot in the head.

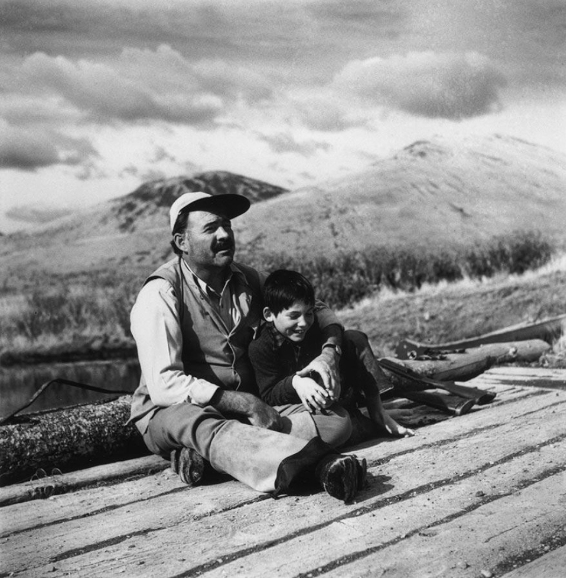

The soldier dies while looking at the empty space in the right part of the photo, which creates a visual that magnifies the soldier’s desolation during his death. Not only is this photo iconic, but it was also incredibly controversial, for Capa was accused of staging the photograph. Also during the Spanish Civil War, Capa became friends with renowned American author Ernest Hemingway, who later became a noteworthy subject of Capa’s photos.

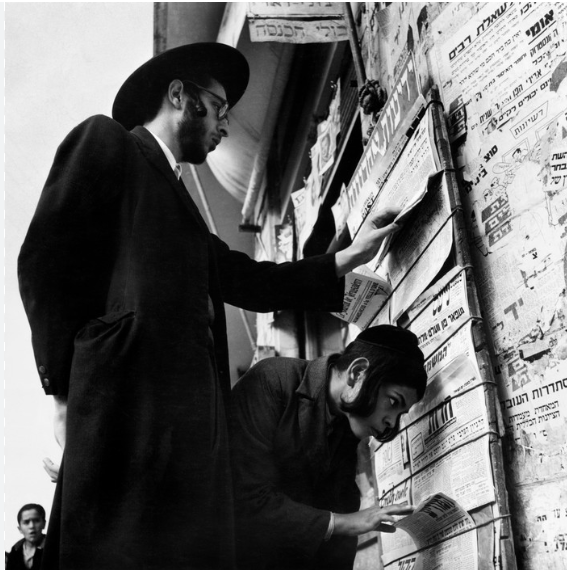

In 1948, Capa visited Israel to witness and capture the ceremony of Israel’s independence, along with the subsequent war. Over the next two years, Capa documented the lives of immigrants who traveled to the new-born state of Israel. In these photos, Capa depicts the Jewish refugees and soldiers as heroic, reflecting his own identity and ideology.

Although Capa shows sympathy towards the Jewish population, he never portrays the thousands of Palestinians who were displaced or forced to be expelled as a result of the Arab-Israeli War. Perhaps this was because Capa himself was a Jew, and he favored their narrative although they were also involved in the foregoing violence and brutality.

In a 1954 exhibition in Japan for Magnum Photos, the LIFE magazine requested Capa to travel to Southeast Asia and take photos of the ongoing anti-colonial conflict between the imperialist French and the Viet Minh. During a combat photo shooting, forty-year-old Robert Capa was fatally killed by a landmine while doing the thing he loved.

Capa’s life was one of achievement, love, and tragedy. He was a photographer, a lover, and a man who chased his dreams. His touching, unprecedented photographs have played a crucial role in remembering and commemorating the historical events of the 20th century – leaving his mark on both the genre of photojournalism and modern history. A pioneer of modern war photography, Capa has paved the way for many new generations of photographers to come.

Montserrat Reyes responds:

Student Feedback:

The early life of a famous person provides a reason as to why they grew up to be the way they are, and focusing on specific moments, like Capa’s involvement in a gang and fleeing from Hungary, help you portray Capa as “fearless, and one to always be seeking adventure”. My favorite part was when you mentioned Capa’s interest in journalism, but because of the language barrier, he became a photographer by chance. It really opens my eyes to how the most unexpecting people normally get the most recognition for their work.

Additionally, Capa’s courage is different from what most people think of when the word is used. Like you said, “instead of a gun” Capa used his photography to show support for the side he was on in addition to risking threats from the opposing side. The fact that he was in danger but still wanted to capture what was truly happening is the action of an unsung hero. As his career goes on, it’s evident that he, and his partner, want to be at the forefront of the biggest conflicts of the time. “The story of Robert Capa and Gerda Taro, two lovers who died for freedom, while doing what they had loved, has inspired many.” Their ambition and bond over making a difference is stunning because it really emphasizes how much more of an impact one can make if another person is beside them.

Capa’s Death in the Making demonstrates how photography is more than a picture, it’s a story that follows real people. The story has super high, and devastatingly low, points that are able to be shown. The thing that I most admire about photography is that the image is already given to you, unlike a book, but your imagination is what expands the story to mean something to you, making it more impactful than a movie. Out of the three, which one most speaks to you?

I think it’s important that you draw attention to how Capa’s photographs connect with his ideas, like when he “depicts the Jewish refugees and soldiers as heroic, reflecting his own identity and ideology”. On top of that, you share that Capa has a bias as to what he documents; you brought up the fact that him being Jewish made him not capture the trouble of the Palestinians. By sharing both the good and bad sides of Capa, it keeps you in the middle which shows that your writing is unbiased and gives the readers a different perspective on him. But, since you did choose to write about him, how did you react when you saw this? Did you distrust Capa for letting his beliefs affect his work?

The way you wrote Capa’s story is CAP-tivating and sentimental. Sometimes, I forget that famous people have a personal life and with this work you bring light to parts of Capa’s life that are as equally important as his impact throughout his career.