A survey of Stephen Crane

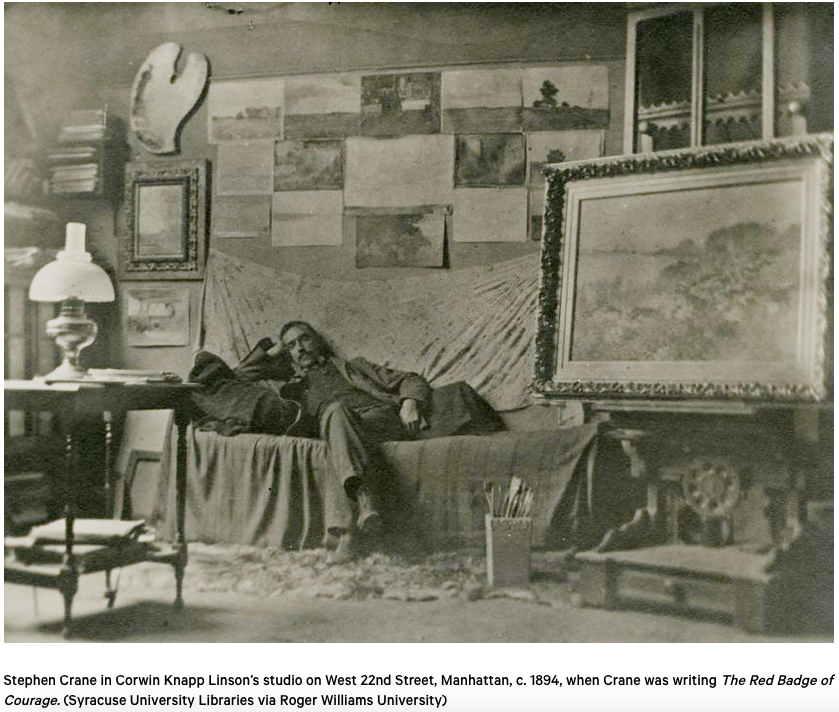

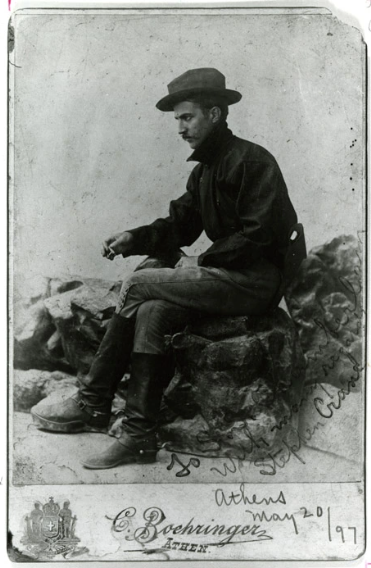

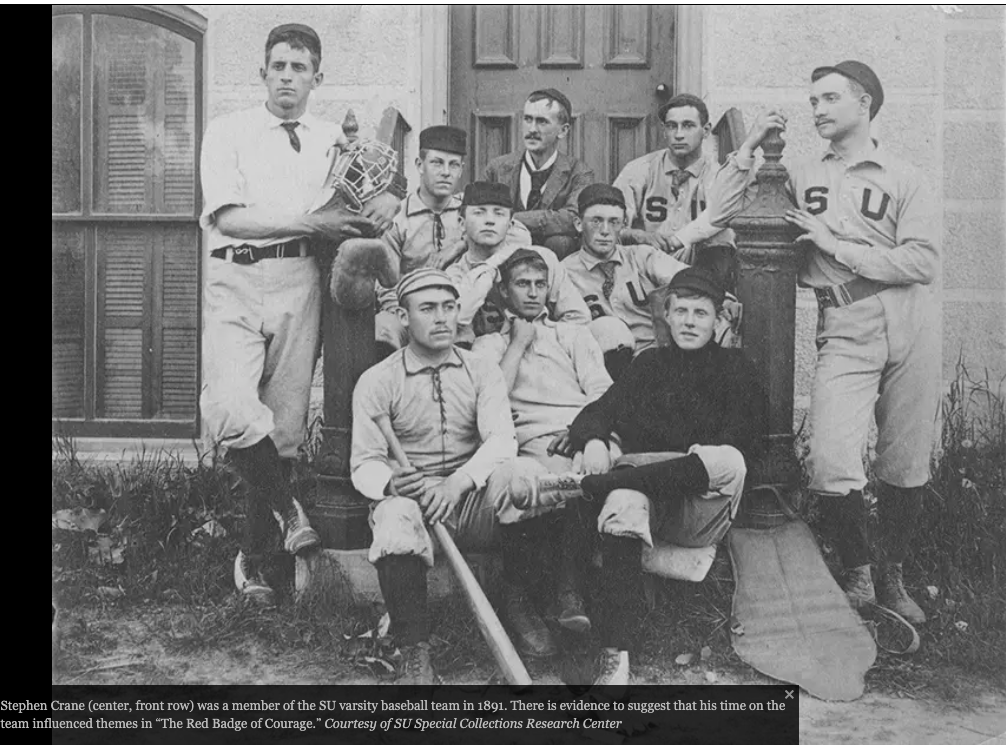

Stephen Crane (1871-1900) was an American titan of literature who pioneered the style of naturalism through his vivid depictions of life and the human condition. Although Crane himself has seemed to have faded away from popularity, his extraordinary works on the human condition continue to live on and have influenced many writers of the 20th century. Despite Crane’s abrupt passing at the age of 28, in 1900, technically the 19th century, his career was certainly significant. Crane’s numerous works portray profound themes of drunkenness, children, and countless more in impressive fashion.

To examine this cause further, I present a survey that not only delves into the fascinations of Crane but also reveals the author’s mentorship through his tales. Further exploration will be done through utilizing Burning Boy: The Life and Work of Stephen Crane, which is both a precise biography that illustrates Crane’s life to death, as well as an illuminating résumé of the man’s numerous stories, written by the late major American author, Paul Auster (1947-2024), a creative force in his own right, not just a Ph.D. who writes biographies.

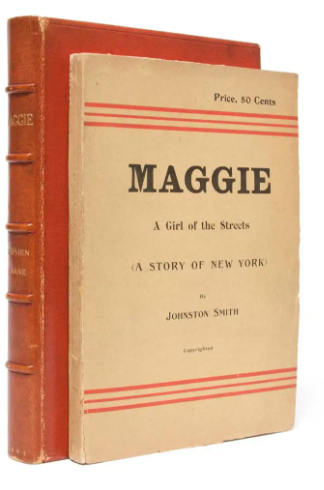

Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, Crane’s debut novel, precisely captures the detrimental consequences of drunkenness. After being rejected by the American Press Association for a job, Crane was in desperate need of a sponsor for his work. The man was at a “shortage of dimes” (Auster, 85), and at Crane’s lowest point economically, he was saved.

Writers Hamlin Garland and Willis Johnson “responded favorably” and supported Maggie, as both men eagerly tried landing Crane a publisher. Despite their efforts, Crane was eventually also turned down by Richard Watson Gilder, editor of the

Century Magazine, who was “appalled by the language” (Auster, 106). Finally, in 1893, Crane decided to fully snatch his only choice available and self-published the book with his own money.

When Maggie was first released to the public, the few Americans who read it were shocked by its vicious realist style and disgusted by its content. Throughout the novella, Crane relentlessly bombards the reader with brutal, evocative scenes. Those who were pious, which included members of Crane’s family, believed it to be “offensive” and “immoral” (Auster 88). With the creation of Maggie, Crane “took his first step” into the world of his imagination, and from then on, his works of fiction touched base on extreme topics like war and poverty (Auster, 109). Critics over the years have attempted to place Maggie into various genres, but it’s evident that “Crane’s slender book eludes all fixed categories” (Auster, 87). Regardless, Maggie will certainly give the reader an experience. Throughout the stunning work, Crane emphasizes the chaos caused by alcoholism through the portrayal of a crumbling family.

The beginning of the story is a first glance at the grotesque world of Maggie. Crane introduces us with a harsh depiction of a New York slum, and things escalate quickly. Immediately, we are met with a monster child, Jimmie of Rum Alley, who is engaged in a fight with the “howling urchins from Devil’s Row” (Crane, 1). The first few sentences of the novel are set the tone, and tone up the setting for the entire book. See this: “A very little boy stood upon a heap of gravel for the honor of Rum Alley. He was throwing stones at howling urchins from Devil’s Row who were circling madly about the heap and pelting at him.”

Jimmie is vividly portrayed as “livid with fury” and his body as “writhing in the delivery of great, crimson oaths”. To establish a fierce yet striking scene, Crane details the battle through intense phrases, powered by potent descriptors. This is seen with the boys of Devil’s Row, who carried the “grins of true assassins” as they howled with “renewed wrath” (Auster, 89). The next character we meet is an older friend of Jimmy’s named Pete, who had a “chronic sneer of an ideal manhood” (Maggie, 3). Pete intervenes in the battle on the side of Jimmie and helps fight off the other boys. The battle continues and Jimmie takes on a head-to-head fight with Billie: “they struck at each other, clinched, and rolled over on the cobblestones” (Maggie, 5). The bloody struggle finally ceases when Jimmie’s father enters the scene. The man steps forth and brutally reproaches his son. “You Jim, git up now, while I belt yer life out, you damned disorderly brat” (Maggie, 6). The father’s bitter words instantly set the tone of the novella: urban savagery, depicting dysfunction at dangerous levels. The chapter ends with Jimmie being taken home by his father. Now, the home of the Johnson family is portrayed as if it was in a “medieval mystery play” (Auster, 91), for Crane calls it a “dark region” where the “gruesome doorways” of the various tenements abandoned their children to the streets of New York. It’s a place of despair, cruelty, and corruption. In this dreadful abyss, we meet Maggie for the first time. She is Jimmie’s sister, a “small ragged girl”, who is seen pulling her younger brother Tommie along the “crowded ways” (Crane, 7).

Shortly after our encounter with Maggie, we meet Mary Johnson: Jimmie and Maggie’s mother, whom Auster describes as a “woman made of both ice and fire” who “does not hesitate to turn against her daughter and denounce her as a child of the devil” (Auster, 99). This depiction of the mother perfectly illustrates her cruel personality, as well as her behavior towards her children. The uncontrollable Mary Johnson, fueled by alcohol, would “destroy furniture and battle with her son,” but would have the seeming dignity to spare Maggie from physical violence and instead “kill her with words” (Auster, 99). The term that Crane uses to portray Mary Johnson is “rampant” (Crane, 9), and as peculiar as it might be, Auster believes that it “fits the person it describes” (Auster, 93). Even with Paul Auster’s vast experience in the field of literature, the acclaimed author writes, “over the course of my life, not once outside of Crane’s book have I ever come across a man, woman or a character in a novel referred to as ‘rampant’” (Auster, 93). By definition, the word rampant means: (of something unpleasant) spreading uncontrollably. Despite the utter brutality of the other “human savages” in Maggie, “the mother is the most savage, the most unstoppable, the most fearsome” (Auster, 93). Through the use of the word rampant, Crane places the diabolic Mary Johnson in a category of her own. She is the villain, but unlike any other traditional figure of evil, the Johnson mother possesses an aura of savagery so devastating and immense that Crane is forced to ascribe her with the one word that can depict her character. In this fashion, Crane designates a spot in hell for her.

The ending of Maggie is astonishing. In the first few sentences, Jimmie enters a room and reveals to his mother that “‘Mag’s dead’” (Crane, 153). The mother begins to weep in a “fugue of self-pitying sorrow” (Auster, 103), and suddenly a crowd emerges, comprised of the other women of the tenement. Auster calls the Johnson mother an actor whose performance is “so persuasive that the others commiserate with her, acknowledging what an affliction it is to be the mother of a disobedient child” (Auster, 103). Here, the utter hypocrisy of the mother is displayed at its finest. In her hysteria, Mary says that she will forgive Maggie even though her own outrages made the family crumble. Moreover, the other women of the building declare that Maggie was a “bad, bad chil’” and has “gone where her sins will be judged” (Crane, 157). Mary Johnson was the one who was truly kin to the devil. She never loved Maggie and her heartless errors ultimately led to her daughter’s demise.

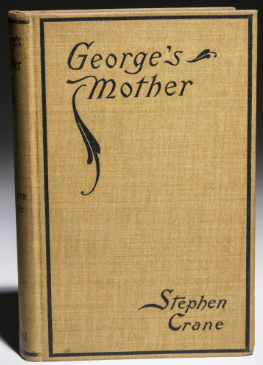

Crane’s sixty-three-page novella, George’s Mother, is a tragic yet truthful tale. Paul Auster figuratively declares that “If Maggie is a book set in hell, George’s Mother is set in purgatory”. But, in reality, George’s Mother is set in the same tenement building as Maggie. It’s a type of obverse sequel. In Maggie, Mary Johnson, as mentioned, the mother of Maggie and Jimmie, wreaks havoc throughout the entirety of the story by destroying furniture, tormenting her children, and screaming blasphemies. This undoubtedly has something to do with her being possessed by the influence of alcohol. However, the mother in this chronicle is far from the nature of Maggie’s mom, for Auster even states that George’s Mother is a “study in gray rather than crimson” (Auster, 209). In a dismal story about the protagonist George Kelcey and his beloved mother, Crane unravels the psychological effects of alcoholism in its beginning stages.

We meet George, a young man who lives with his mother in the same tenement as the Johnson family in New York City. In the very first scene of the story, George is sauntering towards home when he meets Charley Jones, an old acquaintance. Jones asks George to have a drink with him, and soon they are off to the bar. While the two men drink, they talk about the old days. Jones tells George about the “great crowd” that accompanies him at the saloon and asks that George come around and join them for a drink sometime. George says “I will if I can” (Crane, 3). Afterward, George returns home, later than usual, and we meet his mother, “a little old woman”. She walks over to him while “on the verge of tears and [with] an outburst of reproaches” (Crane, 6). It’s a moment that reveals the perhaps too-saccharine care that George’s mother provides.

In Chapter Seven, George meets Maggie Johnson (of Maggie!) in the hallway, who is seen holding a pail of beer and a brown paper parcel. George grows feelings for the girl immediately and soon realizes that “it would wither his heart to see another man signally successful in the smiles of her” (Crane, 17). In spite of George’s infatuation with Maggie, he never takes action. George was, as Auster said, “one of those stifled, maladroit young men who burn with passion but are unable to express themselves” (Auster, 216). Eventually, a suitor named Pete makes his move and seizes Maggie’s heart away. This nightmare coming true makes George burn with rage and he begins to treat his mother poorly because he is ashamed of himself and because he is overwhelmed by vexation. To find solace and companionship, George returns to Charley Jones and without a care at all, or to drown his pain, starts drinking again. As we have seen many times before, Crane builds onto the plot by adding another incident that will both further our understanding of George’s psyche and also set the stage for the downfall of the protagonist, for “the pot is boiling now” (Auster, 218).

As George continues to plummet to his doom, he tries to reform himself. He confronts his guilt by “allow[ing] his mother to talk him into attending a prayer meeting” (Auster, 218), an activity that his mother has suggested to George numerous times throughout the novel, but George has never agreed to because he sees it as a burden and simply doesn’t want to go, regardless of the countless protests and pleas. After attending the meeting with his mother, George gains nothing from the minister’s speech but a mere reminder that he is “damned” (Crane, 29). Despite their efforts at refinement, his destruction is inevitable, and George yields to his alcoholic side. In doing so, he abandons his mother in the dark.

Days pass, and the lingering bond between mother and son begins to break. George has entered a rapid phase of decline. The once reputable young man has fallen down the familiar pit of alcoholism. He finds himself amid a “gang of witless toughs” who spend their time “boozing, fighting, and hanging out on street corners” (Auster, 218). His recklessness and negligence pave the way for his firing, which further agonizes his poor mother when the two come face to face in their apartment – in a “tense, unbearable standoff” (Auster, 218).

The following day, George is standing on the corner with his friends when a group of boys reports to him that his mother is sick. George is struck with fear. Despite the seemingly shattered connection between mother and son, Crane reveals that it is indeed still intact. George hastily returns home, his “eyes quavering in fear” the whole time. He learns that his mother is all right, which instantly relieves him of his troubles. However, George’s commiseration for his mother is only temporary, and the “tender moment does not signify a permanent reconciliation”, for the very next day, George has returned to his old drinking comrades, which includes the one who ensnared him in this destructive habit, Charley Jones (Auster, 219). When George asks to borrow money from them, each man makes a weak excuse to escape his appeals. Now unemployed and desperate, George is looked down upon by the others: “they remained silent upon many occasions when they might have grunted in sympathy for him” (Crane, 38).

“When Kelcey went to borrow money from old Bleecker, Jones and the others, he discovered that he was below them in social position. Old Bleecker said gloomily that he did not see how he could loan money at that time. When Jones asked him to have a drink, his tone was careless.

O’Connor recited at length some bewildering financial troubles of his own. In them all he saw that something had been reversed. They remained silent upon many occasions when they might have grunted in sympathy for him” (38).

After having been “exiled again”, George has lost everything. Except his mother. The man returns home, to the “chamber of death” (Crane, 42). By now, the apartment is busy with people: a doctor addresses George’s mother in the bedroom, a minister comes to replace the doctor, and Mrs. Calloway is “feverishly dusting” and “preparing for the coming of death” (Crane 42). In good health just days before, George’s mother is now horribly ill. The woman cannot even recognize George when he approaches her; she has forgotten him completely. On reaching the end of the story, we see Crane’s irony at play once more. After leaving his mother, who had been nothing but a fostering yet smothering influence, to seek acceptance in the outside world, George shames her for losing his job and becoming a disgraceful drunk. His drinking companions ultimately desert him as he had deserted her. And when the young man finally comes home, he has lost the one person that could have saved him – his mother. The personified city advances, and marked by an “endless roar”, it has come to punish him. In the kitchen, the doctor whispers something to Mrs. Callahan, and upon hearing the news, she begins to “[labor] with a renewed speed” (Crane, 42). George’s mother’s time is expiring and each step the “marching city” (Crane, 44) takes, is another second closer to calamity.

The end of the story is a powerful juxtaposition of the finality of death with the indifference of the world:

The little old woman lay still with her eyes closed. On the table at the head of the bed was a glass containing a water-like medicine. The reflected lights made a silver star on its side. The two men sat side by side, waiting. Out in the kitchen Mrs. Calahan had taken a chair by the stove and was waiting.

Kelcey began to stare at the wall-paper. The pattern was clusters of brown roses. He felt them like hideous crabs crawling upon his brain.

Through the doorway he saw the oilcloth covering of the table catching a glimmer from the warm afternoon sun. The window disclosed a fair, soft sky, like blue enamel, and a fringe of chimneys and roofs, resplendent here and there. An endless roar, the eternal trample of the marching city, came mingled with vague cries. At intervals the woman out by the stove moved restlessly and coughed.

Over the transom from the hall-way came two voices.

‘Johnnie!’

‘Wot!’

‘You come right here t’ me! I want yehs t’ go t’ d’ store fer me!’

‘Ah, ma, send Sally!’

‘No, I will not! You come right here!’

‘All right, in a minnet!’

‘Johnnie!’

‘In a minnet, I tell yeh!’

‘Johnnie—’ There was the sound of a heavy tread, and later a boy squealed. Suddenly the clergyman started to his feet. He rushed forward and peered. The little old woman was dead” (Crane, 43).

There may be commonalities in the themes of Crane’s vast oeuvre, but the author doesn’t isolate his narratives to any one specific genre of literature. While Maggie and George’s Mother were assembled with Crane’s most fiendish elements, the man’s writings about the psyche of children have an entirely different atmosphere.

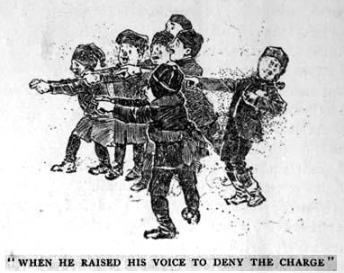

“His New Mittens” is a short work that chronicles the experience of an eight-year-old boy by the name of Horace, and it takes place in the fictional small town of Whilomville, a setting used by Crane in the namesake vignettes, The Whilomville Tales, which collectively are a rare short story cycle. The story begins with a battle (a much less violent one than the opening of Maggie). Young Horace is walking home from school when he sees his friends in a snowball fight. The boy is eager to join but faces two hindrances: his mother had warned him to “come straight home” and to not “get them nice new mittens all wet” (Crane, 1). However, some of the other boys immediately analyze his extraordinary hesitancy and they begin to jeer him with a humiliating chant, “A-fray-ed of his mit-tens!” (Crane 3). Crane proceeds to examine the complex hierarchy that stands within the young group of comrades and the psychological aspects that youth deal with when faced with amusement and abuse. Although Horace has a “sense of impending punishment for disobedience”, he cannot resist the excitement of the snow battle, ultimately resulting in the thwarting of the boy’s diminutive concept of responsibility.

Moments later, Horace’s mother arrives to take him home. He’s “dragged off” by his mother in a humiliating “public scandal” that will surely have a lasting impact on the boy’s status within the friend group (Crane, 9). Crane’s use of the phrase ‘public scandal’ is in some ways a hallmark of this series, which aims to elevate children’s behaviors, their dramas, and their interactions to operatic, dramatic, and even histrionic levels. His mother, upon discovering that the boy has shamefully soaked the pair of mittens, banishes the boy to the kitchen, where he will eat supper alone. With “his heart black with hatred”, Horace plots a scheme to exact vengeance on his mother, who “must pay the inexorable penalty” (Crane, 13). After failing to seize his mother’s attention by refusing to eat, Horace decides that only one final course of action remains: to run away from home. As he ventures out, a snowstorm wreaks havoc violently, which compels the “exiled, friendless, and poor” boy to reassess his decision (Crane, 17). Eventually, Horace finds himself outside the butcher shop of his father’s friend, Stickney. Hanging his head low, the boy enters the shop and is abruptly met with Stickney’s deep concern. Horace confesses to running away from home, which Stickney finds amusing. The boy is led out of the store, homeward, despite his frantic, yet “respectable resistance” (Crane, 21). Horace’s mother is “pale as death”, with her “eyes shining with pain” (Crane, 21). However, when she catches sight of her beloved child, a sudden pulse of relief coerces her to “[fold] him in her weak arms” (Crane, 21). Lost in both grief and joy, Horace gallops towards his mother without a second consideration, leaving his thoughts of vengeance behind.

The mind of a young child is often mystified and even unreasonable. Through extraordinarily expressive exaggeration and a retrieval of blurred memories, Crane illuminates the ethical, emotional, and mental principles and values that exist within the minds of those in childhood.

With your newfound knowledge of this American colossus of twentieth-century literature, go now, and seize the occasion to indulge in the bizarre yet ingenious work of Stephen Crane.