The Home by Christmas Campaign

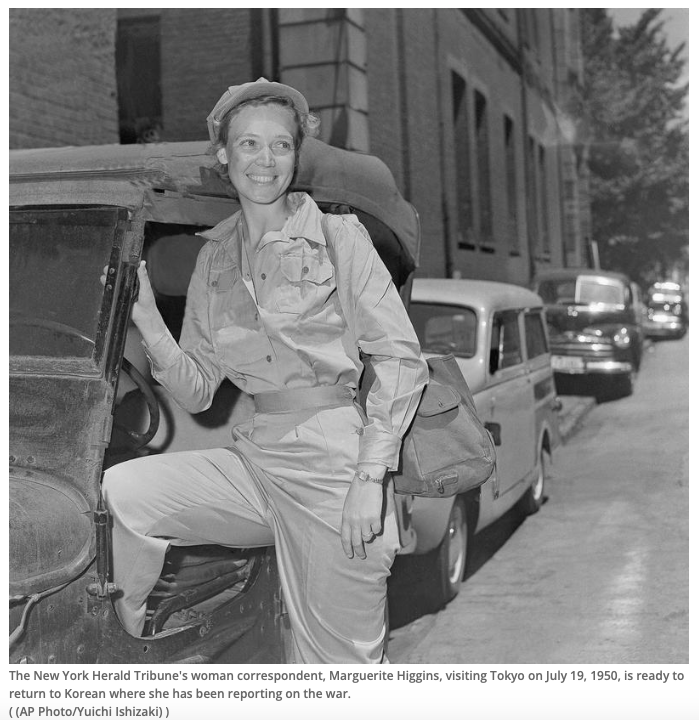

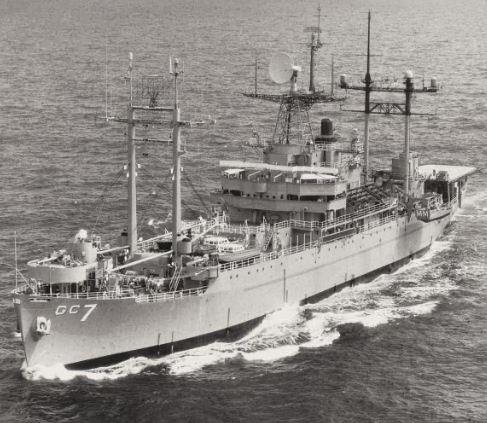

On September 15, 1950, Maggie Higgins woke up to the deafening blast of USS Mount McKinley’s horn, signaling the beginning of the invasion. She sat up, pushed a messy wave of auburn hair from her face, and swung her legs over the bar of the sleeping berth. Ms. Higgins shoved her boots on, shrugged on a jacket, and grabbed her notebook from the nightstand. Outside her room, there came shouts, the voices of Marine officers roaring orders. She waited as a crowd of soldiers shuffled along, tightening their straps, retrieving rifles from their lockers. Maggie clutched her notepad and made her way into the brewing storm above.

A young corporal awaited her at the end of the staircase leading up to the main deck.

“Fine morning, ain’t it, Mags,” he said, grinning.

“Morning, Corporal,” Maggie replied softly. From under the main mast, she looked curiously toward the beach of Inchon. It was foggy, but Mags could see the faint outline of a coastal town. Below her, bustling hordes of American troops had already begun their descent down the ship. Prying out her notebook, she jotted: one by one, the men climb down the long netted rope and into the smaller vessels. The air is now heavy with salt and smoke (the aroma of impending battle), and the ocean contains a subtle shade of green.

Below the ship, hordes of marines were climbing from their landing crafts and up the seawalls.

“Tell me, Corporal, do you think the general’s gamble will pay off?” said Maggie.

“I reckon we don’t jinx it. But something, and maybe it ain’t anything at all, is just telling me the North Koreans won’t see it coming. They’re still licking at their wounds in Pusan.”

“Maybe. I fear that if this fails, we might all be doomed.”

“Well, I don’t know… Ma’am, where are you going?”

“What does it look like? I’m going to document the invasion,” she cried out.

“Ms. Higgins, with all due respect, you shouldn’t be going ashore. It’s gonna be hell out there,” the corporal said.

“Corporal, do you think I came all this way to watch from the sidelines?”

“No, ma’am. But it’s dangerous for a woman to-”

“Oh shut it! I go where the story goes,” she replied, unamused. Maggie waved him off and tucked her notebook away. “I’ll see you on the other side.” And with that, she proceeded down the gangway.

The island was a blur of motion and chatter. Maggie boarded the back of a transport truck, squishing herself in one of the seats between two burly, and rather musty marines, who seemed irritated by her arrival, unwilling to allow any distraction. She ignored them too. The truck rolled forth, following the convoy of First Marine Division vehicles. Maggie began her observations, absorbing every chaotic detail with the precision of her pen and the grace of her hand. She analyzed the faces of the other men, their countenances marked with anticipation as they gripped their rifles with sweaty hands. Today was the beginning of Operation Chromite – General MacArthur’s valiant mission to liberate Seoul before the KPA could recover from the devastating losses in Pusan. The KPA had surged south to Pusan, but their supply lines had stretched too thin. The North Korean forces were vulnerable, and it was the perfect opportunity to strike.

Maggie’s thoughts were abruptly interrupted by the tumultuous sounds of distant gunfire and tank artillery. As the truck advanced, the coastal town of Incheon came into view. It was ablaze. Thunderous bombs erupted throughout the city, which was covered by waves of smoke. Nearly there. The artillery fire began to match the pace of Maggie’s heart and at last, the truck jerked to a halt. The men leapt out of the vehicle in an instant, rifles in hand. Maggie followed suit, sliding out of the carrier and landing hard on the ground. Before she could dust herself off, a stampede of enemy fire snapped into the truck’s steel exterior, jolting her to her feet.

“Keep moving!” the sergeant yelled, waving the men up the beachfront.

An instance of hesitancy was quickly followed by a reminder of what a fellow journalist called Frank Gibney had said before she booked her flight, “Korea is no place for a woman”. Maggie forced herself to move, following the group of Marines she’d accompanied. She kept low, using the trucks as shields against stray bullets. The sergeant threw up his hand, and the men pressed forward into the town. Maggie, hanging back, took shelter behind a fallen house and laid low under a concrete ceiling as she wiped the pool of dirty sweat from her face. Grabbing the notebook from her pocket, she scribbled down everything her eyes, nose, and ears could take in. A nearby explosion sent debris flying into the air, and she threw herself on the ground.

Acting quickly, she traversed the burning battlefield, using fallen trucks as cover. She soon found herself inside a small shed in what appeared to be one of the local’s backyards. Inside, Maggie pressed herself against the wall and took a deep breath of relief. Something of fear, or uneasiness, crept down her spine, but by now she was used to it.

It was back on the 25th of June, and she was still in Tokyo, receiving a rather unpleasant welcome by her colleagues after being named the Chief of the New York Herald’s Tokyo bureau along with Frank Gibney who was correspondent for both Life and Time. That’s when the first reports came in. The North Korean army, supported by tanks and artillery, had crossed the 38th Parallel. A full-scale invasion was launched, and the war began. Only days later, between the 27th and 28th, Seoul had fallen. Without tanks or sufficient artillery to defend themselves, South Korea’s army was on the brink of defeat- within the first week. On June 28th, Maggie and three of her other colleagues witnessed first-hand the Hangang Bridge bombing in Seoul, an attempt by the South Korean army to delay the North Korean onslaught. She’d seen the desperation in the eyes of the soldiers, refugees, and citizens trying to cross. They were killed in an instant.

Gibney, who at the time was trying to get across the bridge with two other correspondents, recalled: “Lit only by the glow of the burning truck and occasional headlights, [it] was apocalyptic in frightfulness. All of the soldiers in the truck ahead of us had been killed. Bodies of dead and dying were strewn over the bridge, civilians as well as soldiers. Confusion was complete… At the same time we wondered if this was the beginning of World War III?”

The very next day, Maggie went straight to the U.S. military headquarters in Suwon. Upon her arrival, General Walton Walker took a meager glance at her and ordered her to fly home. Maggie was furious.

She remembered his exact words: “We got no time to be making accommodations for women. A liability is what you are”. Maggie refused to leave Korea, to leave such a story in the hands of other journalists. She had personally appealed to General MacArthur, demanding the matter be taken care of. Within hours, MacArthur’s telegram arrived at the Tribune: “Ban on women correspondents in Korea has been lifted. Marguerite Higgins is held in highest professional esteem by everyone.” She joined Gibney in the field from that date as chief correspondents to America.

Following the fall of Seoul to the KPA, President Truman authorized U.S. forces to assist South Korea, and over the next few weeks, several other UN-affiliated countries joined the effort. On July 5th, Task Force Smith contested North Korean forces at Osan in the first battle between American and KPA soldiers. While the UN began solidifying a defensive line at the Pusan Perimeter to hold the North Koreans back, MacArthur was planning the landing in Inchon. Now, Maggie was in the heart of Inchon, documenting the war from the frontlines, and no one was going to send her home.

Maggie’s thoughts were interrupted by an airhorn from below the hill. She hadn’t noticed it until just now, but the roar of blazing artillery had faded, leaving in its essence an eerie stillness. Nearby, she heard footsteps. Slowly, she peeked out the window. A pair of marines were approaching her shed.

“Hey!” she called out.

One of the marines, covered in mud and sweat, looked up at her.

“What happened?” she called out.

“We took it,” the man replied, managing an exhausted smile. At the entrance of the town, military trucks were making their way into the city.

“All of Inchon?”

“We took the whole place. Hit ‘em good,” said the older marine who was signaling for one of the drivers.

“Oh my goodness. Well, are you all alright?”

“As good as one can be. Inchon is ours.”

Voices of victory ensued, almost like a tide through the battered city of Inchon. Marines and soldiers alike came staggering from the frontlines, some limping, some grinning in triumph.

Relieved, Maggie joined the men on the truck in the backseat. In true Maggie fashion, she picked up her notebook. It was time to write.

The Battle of Inchon, fought from September 15 to 19, 1950, was more than a strategic surprise attack. It was a complete turning point in the Korean War. General MacArthur’s amphibious landing had shattered the North Korean forces and supply lines, opening up quite the opportunity. But to understand how we arrived at this paramount moment and the origins of the Korean War, we must first take a step back.

Nearly five years before Operation Chromite, the Second World War was fading. Following Japan’s formal surrender on September 2, 1945, Korea, which had been under Japanese colonial control for the entirety of the war, was divided at the 38th parallel between two rising superpowers—the United States and the Soviet Union. In this way, the U.S. could oversee the removal of Japanese forces in the final days of World War II.

The Soviets took control of the North, and the U.S. the South. Over the next few years, North Korea (DPRK) became increasingly pro-Soviet, as they established local communist governments and formed the Korean Workers Party under communist leader Kim Il-Sung. On June 25, 1950, North Korea, backed by the USSR, launched a full-scale invasion of South Korea, crossing the 38th Parallel and easily overwhelming the unprepared South Korean forces. After the fall of Seoul to the KPA on the 28th, President Truman feared that the invasion of South Korea had threatened global peace and security amidst a period of heightened tensions.

In response, the UNSC provided assistance to South Korea against the DPRK, and additionally, Truman authorized American forces to assist South Korea. From July to August, American troops suffered heavy losses in the Battles of Osan and Taejeon.

The US had severely underestimated the firepower of Soviet-manufactured rifles like the Mosin-Nagant, as well as the lethal T-34 tanks in combination with experienced North Korean troops.

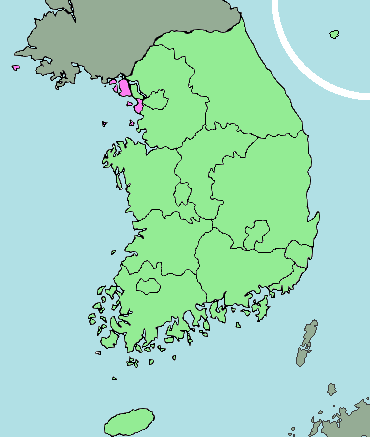

UN and South Korean forces were inevitably forced South, and by mid-August, the DPRK controlled a vast portion of the peninsula.

However, a UN defensive line emerged at the Pusan Perimeter, and they held firm against the North Korean advance with reinforcements from the U.S., Britain, and other allies. Around this time, MacArthur launched his plan on Inchon, and with Seoul back in UN hands by late September 1950, the momentum of the war had shifted.

The North Korean army was now in full retreat, for their supply lines had been cut and their forces annihilated by the augmented UN army. Here, the UN was presented with the opportunity of ending the war entirely with a ceasefire. But General MacArthur had other plans. He was determined to unify the peninsula under absolute Western control. In early October, UN and South Korean forces pushed past the 38th Parallel, advancing towards Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea. Despite the rapid push onward under MacArthur’s orders, the general had failed to recognize the reports that began to trickle in.

China’s Mao Zedong had repeatedly warned Truman that a potential crossing of the 38th would not be tolerated. A growing uneasiness began to spread throughout the ranks, and even with these concerns in mind, MacArthur dismissed them. On October 19th, Pyongyang fell to the UN forces. Optimism resurged, and perhaps MacArthur’s vision had truly been faultless. But in the distance, beyond the peaks of Taebaek, an army was assembling.

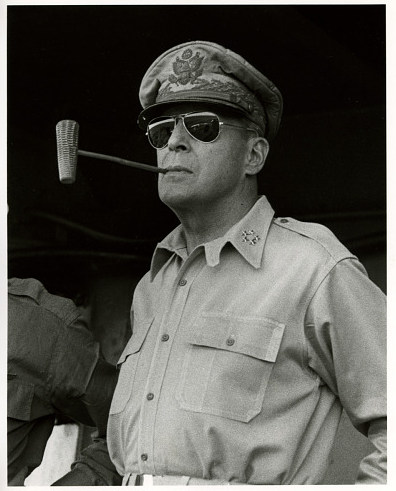

October 26th, 1950. Pyongyang was in ruins. What was once the heart of Kim Il Sung’s regime had been completely overrun by the UN troops. On the outskirts of the bombed city, General MacArthur viewed the destruction from atop an isolated airfield. Clenched between his teeth was a corncob pipe; he gazed upon the remnants of war in the distance. The general beckoned his staff to the table. A map of Korea was laid out, and MacArthur pinned his finger right at the thick line marking the Yalu River

“Gentleman, we are on the verge of victory,” he said. “Pyongyang is in our hands. Seoul has been freed. Korea will be reunified from commie scum. We do not hesitate, nor stop at the 38th parallel. We march on to Yalu.”

A murmur spread throughout the gathered officials. Then, a hesitant voice spoke.

“Sir, what about the reports? The Chinese are coming from North of the river. Our reconnaissance team has picked up heavy radio traffic.”

“Major O’Rourke, are you a fool? Mao and the Chinese wouldn’t dare challenge our military. We have crushed the North Koreans in mere weeks. I assure you, if they did intervene, which I highly doubt, they wouldn’t last days,” chuckled MacArthur, dismissing the man.

Another officer interrupted, “With respect, General, even if the Chinese aren’t considered a threat to our campaign, the coming winter certainly will be. The North’s below-zero temperatures and frozen mountains could eradicate the troops. Our men simply aren’t prepared.”

“Neither are the communists. We march on.”

Aboard Bataan, MacArthur’s personal Lockheed VC-121 airplane, the general sat relaxed in a reclined, golden brown leather chair. MacArthur preferred to travel not like a general, but like a royal king. As the man pondered in stillness, he took puffs from his corncob pipe. MacArthur reopened a report from the Wake Island Conference, which had been held just eleven days earlier, on the 15th of October, 1950. It was his first time meeting President Truman in person, and in those brief moments, he had assured the president that the fate of South Korea and UN involvement in the war would be safe in his hands. Truman’s exact words had been, “What will be the attitude of Commie China?” And to that, MacArthur responded with a promise: the Chinese would not intervene in the Korean War. He declared the North Koreans finished, their capital about to fall, and that the war would be wrapped up by Christmas. Only days after his statements at Wake Island, Pyongyang fell to UN forces – just as MacArthur had assured.

The general sighed and laid back. Something felt off. MacArthur’s intelligence community normally echoed his own views, leaving him vulnerable to crucial reports that he tended to dismiss without a second thought. But today they’d been actually vociferous. He had always understood that if you “control intelligence, you control decision making”, but this usually resulted in his officers simply giving him intelligence that only reinforced his already-held views. In other words, MacArthur was surrounded by sycophants. The CIA, America’s new civilian intelligence agency was prohibited from his operations, which included preparing intelligence estimates for the Eighth Army, the major U.S. Army command in the region.

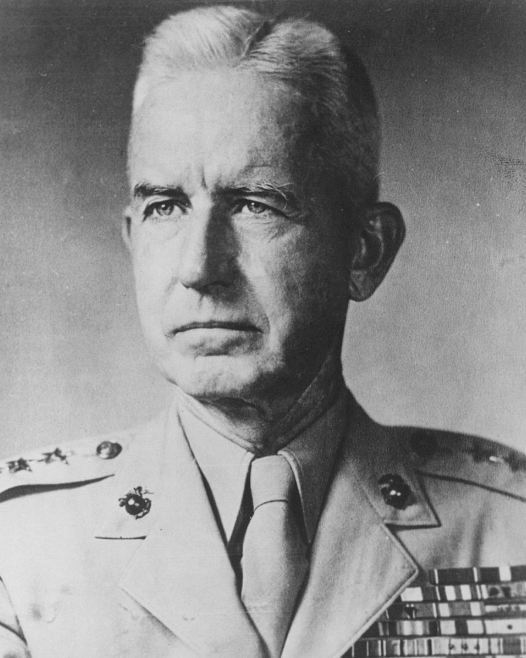

One of the general’s greatest admirers was also his G2. General Charles Willoughby served as MacArthur’s primary source of intelligence. Earlier that year, in June of 1950, Willoughby had assured MacArthur that North Korea would not invade the South, even though alarms had been repeatedly raised by CIA director Admiral Hillenkoetter.

This entire system of reconnaissance was inherently flawed. Reports that contradicted MacArthur’s stance would often be filtered, and naturally, these included warnings about Chinese troops moving across the Yalu River. MacArthur sat up and peered out the reinforced leaded glass of Bataan, snorted derisively at the thought of these hut-dwelling idiots with uniform haircuts and funny hats making a stance against the great eagle nation. Unbeknownst to him, more than 260,000 Chinese soldiers had already crossed into Korea. General MacArthur was feeling a little sleepy, and as Bataan entered Japanese airspace, he reclined his seat and dozed off.

Just 6 days before, on the 19th of October, an immense wave of Chinese forces secretly crossed the Yalu River, marking the launch of Chairman Mao Zedong’s First Phase Offensive. Not a single Chinese soldier had been detected by UN intelligence. But how had they managed to do this? For months, the Chinese had been strategizing. In mid-October, CPVA troops began their expedition across the Manchurian border into North Korea. The strategy that had covered them for weeks from UN inspection was simple, yet alarmingly effective. A conservative notion of subtle camouflage during the day prevented any sort of UN aircraft to detect their intruding movements. During the night, however, they would advance, completely shielded by the darkness. At this time, MacArthur had remained blindsided by his motivations to show dominance, to flaunt the superior battle strength of the American army in the face of the East’s communist regimes.

The general’s smugness was wiped off his face on October 29th. In one of the first major engagements between Chinese forces and the ROK, the Chinese gained a decisive victory at Onjong. They proceeded to win the Battle of Unsan November 4th. It was one of the largest and most devastating losses for the US in the Korean War, with over 600 casualties from the 8th Calvary. By November 6th, the First Offensive ended at Pakchon. It was a huge success – the Chinese gained significant ground, halting the UN advances and pushing their forces southward. Something needed to happen, and on the 24th of November, General MacArthur had an answer for South Korea: “The Home by Christmas” Offensive.

Since early November of that year, 1950, senior officer Edward Almond had been ordered by MacArthur to mobilize the 1st Marine and 7th Infantry divisions to the Chosin Reservoir, and from there, advance to the mining town of Kanggye where they would repel the North Koreans further towards the doorstep of China. This plan, however, required a fifty-five-mile march through the ferocious climate of the Taebaek Mountains.

The US and ROK soldiers experienced unprecedented levels of aggravating fatigue from both the extreme cold and the rugged terrain. Nonetheless, after establishing bases at the Chinhung-ni and Kot’o-ri villages along the road to the reservoir, they began their final march to Chosin on November 13. Most of the 7th Marines reached the town of Hagaru-ri on November 15, while the 5th Marines moved up the reservoir’s right bank. But at this time, General Smith called an operational pause to delay risky deployment and to add reinforcements to the 7th Marines on the east of the reservoir with the 31st Infantry Regiment, also known as Task Force MacLean. This also allowed for the defenses in Hagaru-ri to be fortified and the construction of an emergency airfield. In late November, the X Corps, composed of Task Force MacLean and the rest of the 7th, was advancing towards the Yalu River.

Meanwhile, on November 24th, the 8th Army went on the offensive along the western side of the reservoir. MacArthur hoped that the “Home by Christmas” offensive would not only end the war, but also make a statement. Communism would be eradicated in Asia – and if that meant conquering an entire nation, so be it.

November 24th. Hagaru-ri Camp. The biting winds of the northern climate pricked at Maggie’s skin like sharp needles. She stood at the edge of the towering command post, watching over the campsite that had been hastily set up in close proximity to the vast and utterly frozen Chosin Reservoir. Her breath formed clouds in the cold air. Despite the bitter cold, the sounds of war were still present. The rumble of trucks indicated the arrival of more troops, and the low murmurs surrounding the bootcamp added on to the settling uneasiness.

Maggie’s thoughts took her attention off the aching feeling on her skin. She reminisced back to the beginning of the war, back to her time in Tokyo. She had begged to stay in Korea, despite her colleagues’ strong disapproval. She remembered the threats that had been made towards her: “You’ll be fired if you go back to the front”. She relived the scene of photographer Carl Mydan’s ferociously contorted face, as he growled, “What’s more important, Maggie, covering this war– or fearing you’ll lose your job?” She still remembered the putrid smell of his hot breath. Maggie gagged. Even with all the second-guessing, she had still took the risk, and someone had seen her worth.

Ms. Higgins had first bumped into MacArthur back in June, at Camp Walker – one of the first meetings of the war. Maggie’d stood outside the general’s tent with her notebook tucked tightly under her arm. She kept her eyes on the flap of the tent because she could feel senior officers’ stares on the back of her neck. Some seemed curious, some skeptical, and some irritated. But one in particular felt like a burning ray of animosity. Then the tent flap opened. A voice called from inside.

“Come in.”

She entered and was immediately hit by a thick cloud of smoke. The general stood behind a mahogany-colored desk covered in papers. He offered her a chair.

“You’re from the Tribune?” asked MacArthur roughly, glancing up from his map.

“Yes, sir. My name is Maggie. Maggie Higgins.”

“Well, Miss Higgins, I suppose the reason you’re here is to ask for permission to stay in Korea?”

“Yes, sir. I’ve come to request to report from the front.”

MacArthur looked up. His pale eyes sharply aligned with hers. Maggie blinked hard.

“General Walker seems to think you’re a distraction. He-”

“Sir, I came here to report the truth. I really couldn’t give half a damn about what Walker has to say. The world deserves to know what’s happening to our soldiers. If I’m sent back to Tokyo, the truth will be lost.”

MacArthur eyed her in silence. Then he spoke, “You’ll be in danger here, Ms. Higgins. If you do choose to stay, there’s a risk that you must take. War is a dangerous place for any woman, but especially a reporter of your caliber. There will be no safety nets. There will be nothing at all.”

“With all due respect, sir, my sex didn’t stop me when I was in Berlin, and it certainly didn’t stop me on the Han River, where I crossed on a raft after the explosion of the bridge. My experience is superior to that of any other reporter in Korea. I want this opportunity. Please, General.”

He gave the smallest of nods, then turned to his aide. “Send a message to the Tribune. Let them know the ban is lifted.”

Back in the village of Hagaru-ri, Maggie was settling in for the night. Three days had passed since her arrival at the town. Today was the 27th of November. She lay beneath a wool blanket, with her notepad tucked under her pillow. Despite her attempts to absorb as much body heat as she could by hugging herself tightly, the cold still seeped through the blanket. Outside, the boots of Marine guards crunched against the icy earth – it was a comforting sound.

It seemed as if Maggie had just closed her eyes when the tearing sound of artillery echoed throughout the valley. The ground beneath her bed trembled violently. Maggie jolted upright.

The small village of Hagaru-ri resided inside a barren plain on the eastern side of the Taebaek range, narrowly bordering the southern tip of the reservoir. The camp consisted of a scatter of hastily built tents and wooden shacks. On the perimeter, a wall of sandbags had been aligned, and stretching from the center of the village to the edge of the reservoir was the half-constructed airfield. The town was very lightly defended because Hagaru-ri was essentially a base for support units, and the core population was composed of engineers, medics, and supply personnel. In spite of its insignificant oversight by only two battalions, Hagaru-ri served a number of important purposes, of which included its role as a storage for military supplies and its being the headquarters of General Smith and the 1st Marines.

Inside the camp, the air was thick with smoke and frost. The men and women, exhausted from a long day of service, began turning in for the night. Maggie too, was settling in. She laid down beneath a wool blanket, with her notepad tucked under her pillow. Despite her attempts to absorb as much body heat as she could by hugging herself tightly, the cold still seeped through the blanket. Outside, the boots of Marine guards crunched against the icy earth – it was a comforting sound.

It seemed as if Maggie had just closed her eyes when the tearing sound of artillery echoed throughout the valley. The ground beneath her bed trembled violently. Maggie jolted upright.

The rattle of machine guns opened fire on the camp. A second blast outside of Maggie’s tent forced her to duck behind the bed. Outside, Marines shouted violent orders and began to return fire. The calming night had quickly turned into a bloodbath. Maggie threw on her coat and rushed out the back door. Soldiers rushed past her, cursing and shoving. She followed them, praying that a stray bullet wouldn’t connect with the back of her body. Diving behind a trailer, she turned on her flashlight. In the darkness, Maggie heard General Smith’s voice from behind her.

“Hold the east side! If we lose the airfield, we lose every man here!” he barked.

Another explosion rang throughout the village, and now the night was lit with flames. The Battle of Chosin Reservoir had begun. The Chinese, recognizing their superior numbers, reorganized themselves for a formidable push. Over the river, unknown to General Smith, a second unit of Communist troops prepared to surround the isolated UN garrison. On the eastern side of the reservoir, communication lines had been cut, and Task Force Faith had been ambushed by another predominant Chinese force. With the road south between the camps of Yudam-ni and Hagaru-ri no longer being an option, reinforcements would be put on hold. The only choice now would be to hold the line until another UN task force could be sent northward to open up the road.

“Fire the mortars!” General Smith commanded.

A blinding light ensued, and cannonballs crashed against the Chinese waves. Grenades were thrown over her head. Recognizing that her position was going to be revealed at any second, Maggie hoisted a sandbag over herself and ran for her life up the village. Snow began to fall, quenching some of the fires, but these were seconds later reignited by artillery. Suddenly, a hand grabbed Maggie by the arm. Anticipating a knife to the chest, Maggie closed her eyes.

“Wake up!” roared Colonel Ridge, pushing her into the hands of two nurses.

The aid station was in chaos. Wounded marines lay abutted on cots all around the room. Maggie was led towards a corner of the room and given a light blanket before the nurses hurried away. Outside, General Smith was still shouting orders. For the next forty-eight hours, Maggie barely slept– she went back and forth from the station to surrounding tents, juggling ammunition management with writing. Several days of battle ensued, and the lack of UN manpower became all too evident. Fighting began to slow and exhaustion was ubiquitous. Maggie watched an increasing number of battered soldiers stumble into the arms of nurses: many of whom had previously held positions as engineers and clerks, but suddenly took up arms. The Chinese Communist forces had taken control of almost all of East Hill outside Hagaru-ri. At this point, it was clear. A retreat had to commence.

General Smith, having come to this realization perhaps too late, called for Colonel Puller of the First Marine Regiment to assemble Task Force Drysdale to be sent north from Koto-ri (a neighboring village that was to the south of Hagaru-ri) in an effort to clear the way for withdrawal. On November 29th, Task Force Drysdale, composed of 300 infantrymen, finally came to their aid.

On December 5th, the first group from Hagaru-ri, which included Mags, began their 12-mile journey south to Koto-ri. The march out of Chosin was a nightmare. Along with freezing temperatures, Chinese squadrons pursued them ruthlessly, striking at night and engaging in constant skirmishes along the trail.

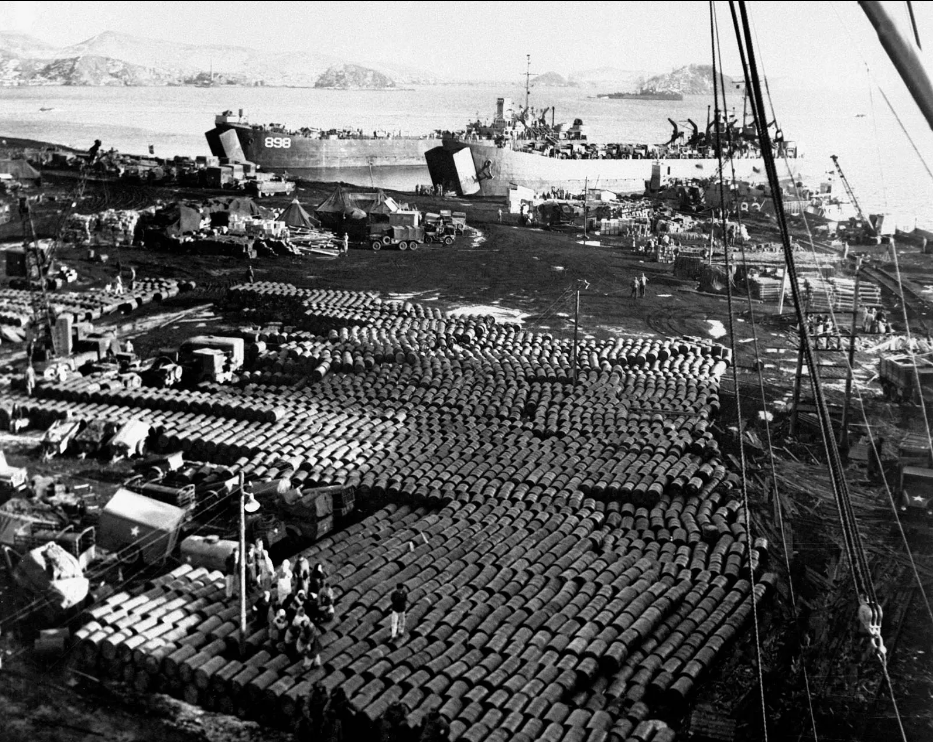

Ultimately, around 105,000 troops, 17,500 vehicles, 350,000 tons of supplies, and nearly 100,000 Korean civilians were carried to safety. Maggie recorded every moment.

By December 11th, Maggie reached the port of Hungnam with the remaining X Corps. An armada of American ships awaited them at the dock. However, they were not set to sail until nearly two weeks later. In that time, tens of thousands of Marines and refugees poured into Hungnam, desperate to escape before the Chinese closed in. Artillery thundered day and night as UN forces kept the enemy at bay long enough to load the ships. Maggie stood on the docks, taking notes of lines of children in rags, mothers carrying babies, and bloody warfare. She helped where she could: lifting luggage, calming frightened families, handing out water.

Ultimately, around 105,000 troops, 17,500 vehicles, 350,000 tons of supplies, and nearly 100,000 Korean civilians were carried to safety. Maggie recorded every moment.

On December 24th, the last explosives were set to destroy the port. Maggie boarded a transport ship packed with refugees and exhausted Marines. The engines rumbled beneath her feet, vibrating through the deck. The ship turned toward the open sea, and ahead, the waves carried her, and her story, south. Locating a seat on the bow, she raised her pen.

Maggie stepped back into the battlefield.