Going Solo by Roald Dahl: the responsibility of a citizen

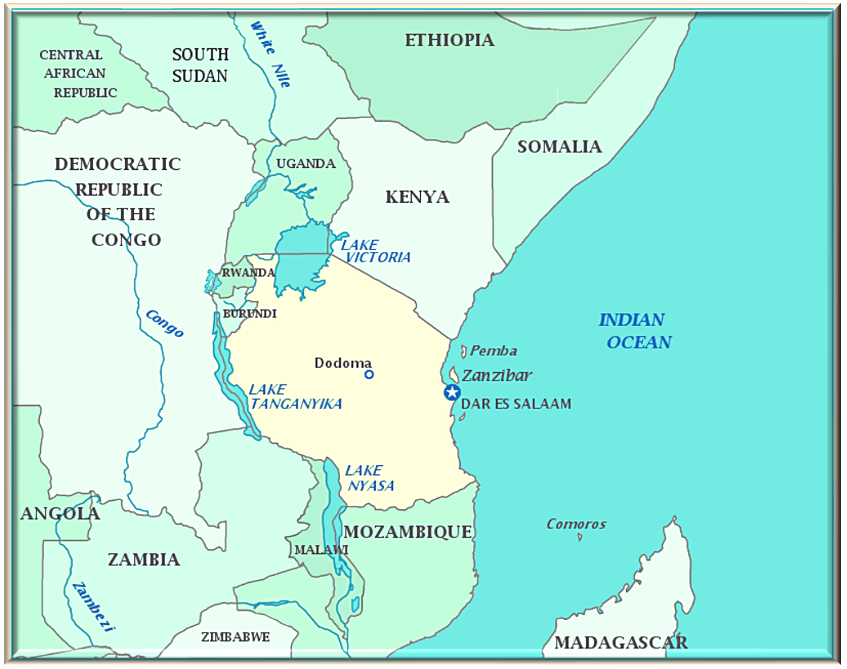

In the chapter “The Beginning of the War” from Roald Dahl’s memoir Going Solo, the war between Germany and England erupted. It was just a few months prior to this that Dahl came to Dar es Salaam, which is a city in present day Tanzania. Tanzania is hybrid word made up from the names of the two previous locations: Tanganyika and Zanzibar.

Dahl was ordered to capture Germans and was assigned to lead “twenty five highly trained troops with rifles” and also given a “machine gun”. He was shocked by this order; he could never imagine that he could suddenly become a soldier, much less an officer who can command soldiers to kill. To Dahl, it was done “by some magical process”, as only a moment ago he had been an employee of the Shell Oil Company. This type of violence was rarely seen or unknown in Dar es Salaam. The only use of a gun seen in the past chapters was only for scaring the “simba” or lion away.

Dahl was a subject of the British Empire, but he wasn’t a soldier; he came for his job and a few years of adventure in this beautiful place. In the few months that Dahl had been in Dar es Salaam he did nothing so violent like killing a person: he learned Swahili to communicate with his “own boy or with any other native of the country”, he helped to save “the cook’s wife” from the “huge lion” or “Simba”… he came to do the Shell Oil Company’s job. Dahl was a citizen who privately helped the British Empire control Dar es Salaam, but again, he wasn’t a soldier; he didn’t have the ability and responsibility to face and use violence.

Dahl’s first assignment was to block the one road out of town. He settled “the machine gun and rifles”, aiming down the road at the approach of German civilians. Dahl instructed his African troops to hide in the bushes next to the road and ordered the soldiers to fire a “burst over the heads of these people”, but “not at them” when he “raise two arms above [his] head”. For a brand new officer, untrained in military strategy, this was a brilliant move.

A convoy of Germans soon appeared on the horizon and came barreling towards Dahl, “stretching for a half a mile down the road”. These cars and trucks were laden with the possessions of these Germans, who were trying to get out of British control as fast as they could. Entire families were fleeing. “There were trucks piled high with baggage. There were ordinary saloons with pieces of furniture strapped on their roofs. There were vans and there were station wagons.”

The lead car, containing two men “beside [the driver] himself in the front seat” stopped and got out. One of these men was about to die, but he did not know it. The man about to die, a bald man, was “angry and his movements were full of menace”. He signaled to the line of cars pulling up, and the drivers stopped their cars and approached Dahl.

“I didn’t at all like the way things were shaping up”, Dahl writes. Do you want to know what happened next? Read the book.

It is not a citizen’s job to fight; it is a soldier’s responsibility to fight and defend. Dahl marched himself from a safe citizen to soldier in danger, and the most important point is that he wasn’t forced. It requires bravery to do such a thing. Holocausts, massacres, and violence flooded the world; no civilians can pull themselves out of this. About 50-85 million people were killed, and if Dahl wasn’t clever enough, he, as a civilian, may have already died in the hands of one of those German civilians.

But I can tell you that the Germans were sent to a prison camp, a place that mainly imprisons captured soldiers. These camps are frequently seen in World War Two, and not only Britain built them; the Germans, the Japanese, even the United States and most countries all over the world built prison camps for the soldiers of the enemy. Civilians were also imprisoned.

To me, there seems to be no reason to capture civilians. But, in a war like World War Two, did the Axis Powers treat foreign nationals as civilians? No. Germany kicked out ambassadors and illegally held Americans, for instance, in prison, without permission. The Allies too, fought dirty sometimes. The British rounded up Germans, Austrians and Italians, calling them ‘enemy aliens’ and men between the ages of 16-70 were sent to the Isle of Man. From what I’ve learned about this great conflict, the Japanese overtook parts of China, mercilessly slaughtering civilians; Germany was obviously rounding up civilian Jews and others they deemed subhuman, and even the USA rounded up civilian Japanese and put them into internment camps.

Who knows: will the ones you let go today kill you or your fellow citizens tomorrow? This is war; to Dahl, and every person that wills to survive, letting go a person who is saying “vi are civilians”, back to their “Fatherland” is no different than giving soldiers back to the enemy.

Obviously the war between Allies and Axis powers was not only around Dar es Salaam; the danger in war was not only capturing a few Germans: this was just the beginning.

In the chapter “Flying Training”, Dahl writes about how he “join[ed] up [to] help in the fight against Bwana Hitler”; he had to first “set off [alone] on the 600-mile journey from Dar es Salaam to Nairobi to enlist in the RAF”. In this Dahl looked around at the natural animals of Africa; he realized that this may be his last laid-back and safe moment. This is the car he drove:

In the period of time Dahl is training, Dahl trained on “Tiger Moths” and “Hawker Harts”. Then at last he was ordered to go to war: he was sent to fight the Italians.

Generally the chapter reveals that Dahl, in “join[ing] up, sheds his last vestiges of childlike ways.”

At this point (1941) of WWII the Axis Powers were frequently expanding their territories. The Germans had just joined the Italians in Greece… mere days before Dahl arrives from Africa, his 6’6″ frame cramped into the cockpit for the solo flight over the Mediterranean.

In the chapter “First Encounter with a Bandit”. Dahl arrives in Greece to fight the Axis Powers. But what he learns upon arrival from his corporal is that he’s joined a base with only “Four Blenheims and fifteen ‘urricanes”; they had to fight “five ‘undred Kraut fighters and five ‘undred Kraut bombers”. They are “absolutely hopeless”.

Dahl is concerned; how will he succeed in this enlistment? He has been nearly blinded and killed because of wrong information given by “the CO at Fouka”, and now he has been sent to this deadly war zone in a cramped cockpit. Imagine being Dahl, would you think you could survive in this harsh condition?

Dahl meets a person named “David Coke” who is also a pilot that “share[ed] a tent” with him. David “came from a very noble family” and if he wasn’t killed later, “he would have been none other than the Earl of Leicester owning one of the most enormous and beautiful stately homes in England”. David informs him: “the bombers you will meet will be mostly Ju 88s”. This later saves Dahl’s life.

The morning after arriving, Dahl is sent out on his first mission.

The first order Dahl had heard in his earphones was “‘Bandits over shipping at Khalkis. Vector 035 forty miles angels eight'”.

“‘Received,’ [Dahl] said. ‘I’m on my way'”.

“The translation of this simple message, which even I could understand, told me that if I set a course on my compass of thirty-five degrees and flew for a distance of forty miles, I would then, with a bit of luck, intercept the enemy at 8,000 feet, where he was trying to sink ships off a place called Khalkis, wherever that might be.”

Dahl has soon encountered his first hostile; “they were Ju 88s” and there were “six of them”. According to Dahl, “there are three men in a Ju 88”, “so six Ju 88s have no less than eighteen pairs of eyes”. This means that Dahl has to pay 100% of his attention, or else he would be immediately shot down.

As a reaction to the encounter of the bandits (not bandits, but actual Luftwaffe Nazi airmen), Dahl has quickly “turned the brass ring of [his] firing button from ‘safe’ to ‘fire’”; he is preparing for a bloody fight.

When Dahl was just “about 200 yards” behind the bandits, they “began shooting at me [Dahl]”. He realized that he had got himself into “the worst possible position for an attacking fighter to be in”. Dahl has to fight six “Ju 88s” that have already spotted him. How can Dahl succeed in fighting back? Or how can he survive?

The change has come: “the passage between the mountains on either side narrowed and the Ju 88s were forced to go into line astern”. Then, BOOM! Dahl shot the closest plane to him in line: the engine poured out “black smoke”, the aircraft “began to lose height”, the pilots and airmen “jumped out”, and “the five remaining Ju 88s had disappeared”.

This interruption may not have much impact on Dahl’s mission of rescuing Greece, but it has surely given Dahl a warning of what he will face later in war.

I admire his bravery like how I admire his literature; not everyone can be so brave like how not everyone can be so skilled in story writing. His act of participating in the war, stopping the Axis Powers rises him from only a talented writer to a hero; a hero that protects both his country and the world and millions of kids’ childhoods (with stories).