The War which made the US a Big Boy Nation

At first, in 1492 (we all know this year… in 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue), Queen Isabella’s Spain was the first European nation to sail to the west, explore and colonize the countries on this side of the hemisphere. Spain was a great imperial nation, conquering areas from Virginia to Tierra del Fuego, which is the tip of South America and areas as far west as California. But by 1825, Spain had lost control of much of this land, and by the time the Spanish-American War came along in 1898, they only had Cuba, Puerto Rico, Philippines, Guam and a few other small islands. The Spanish hold in the New World was feeble, and the US wanted to smash it.

When the Spanish-American war started, America had already expanded to cover ocean to ocean, had expanded south into Texas, Arizona, etc., built the Transcontinental Railroad, and suffered from the Civil War. The US was a growing nation, and starting to make a name for themselves, but people felt that in order to really become a Big Boy nation, we needed to go out of our country and conquer. Cuba was the perfect option.

Frederick Jackson Turner, an American historian, famous for his frontier thesis, felt that a solution for the US could be found beyond our borders, and that now it was time to leave the country and find more land. He believed that this would propel the US forward, and many people caught on to the idea. Turner wrote in his frontier thesis, “Thus the advance of the frontier has meant a steady movement away from the influence of Europe, a steady growth of independence on American lines”. Equally important in the buildup to war was the fact that, through the American eyes, Cubans were suffering, and we should help them. Americans felt that anything was possible if you were an American – but this wasn’t the case for Cubans. They were not free; instead they were being controlled by the Old World, the brutal Spanish, and it seemed to some that it was up to us to free them. Leading up to the moment Americans felt they had to enter the war, we can see that the Cubans had already been trying to fight for their independence for many long years.

First, in 1868, Cuban sugar planters started to rebel against the Spanish. This was led by Carlos Manuel de Cespedes (1819-1874). He claimed independence and formed the Republic of Cuba on October 10, 1868. He also wrote a constitution that got rid of slavery and annexed Cuba to the United States. On October 10, the start of the Ten Years’ War (1868-1878), he issued a cry of independence, also known as the Grito de Yara, which started an all-out military uprising against the Spanish. On this day he also signed the manifesto which showed the aim of the revolution. The Ten Years’ War really peaked during 1872 and 1873, but it started going down again when Cespedes died. After this, General Maximo Gomez (1836-1905), who was also a leader of the rebel groups, attempted to invade western Cuba, which failed because most slaves and sugar producers did not join the rebellion. Soon after, in 1878, Gomez ended the campaign, and the Ten Years’ War was concluded.

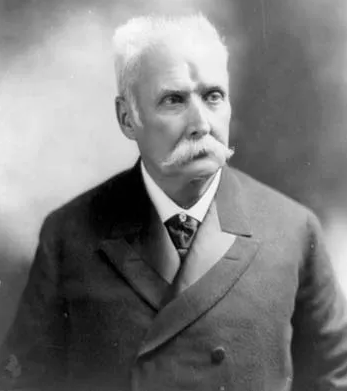

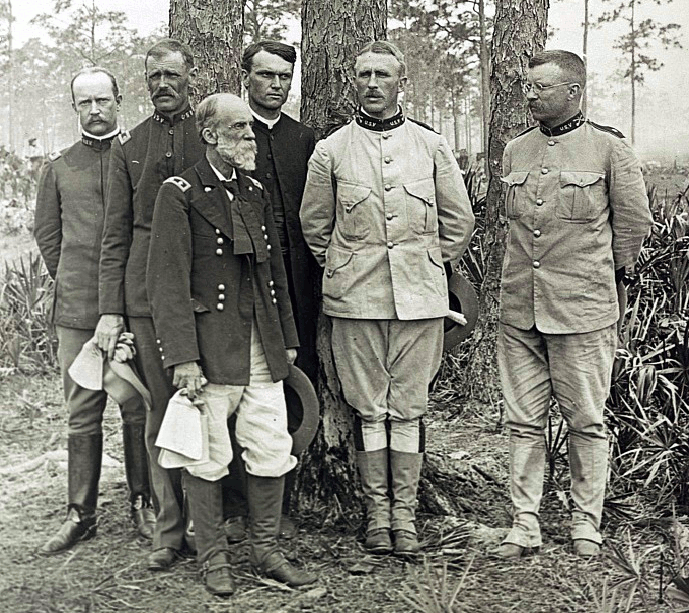

This lack of support for the rebellion, along with Gomez’s failed invasions, forced the Cubans to sign the Pact of Zanjon. This pact was signed on February 10, 1878, by a group of people representing the rebels. The document was written by the Spanish and personally offered by General Arsenio Martínez Campos,

(1831-1900), a dogged pursuer of peace. It wasn’t a military victory, but both sides were tired of the battles, and this relieved everyone, though the Spanish did leave with the upper hand. They had 250,000 troops stationed in Cuba, and this resulted in weakening any Cuban liberation resistance. But the Cubans weren’t done.

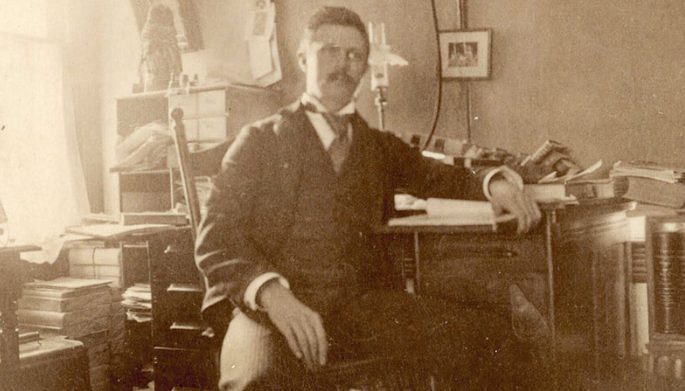

Next came the Little War (1879-1880), led by Calixto Garcia

(1839-1898), one of the few Cuban rebels who did not sign the Pact of Zanjon. In some ways it was like a continuation of the Ten Years’ War, but the difference was everyone was tired and done revolting. The years of bloodshed and war before this one had left the Cuban forces exhausted and ready to give up. To make it worse, they had no foreign nations to offer a helping hand, and not enough weapons to do much damage. People didn’t believe victory was possible, and they felt the next best thing was peace, and so it fizzled out.

With the Spanish promising reform, but not actually doing it, another revolution started 15 years after the Little War. It angered many that Spain was continuing to twist their way out of everything they said they would do, including following up on peace treaty conditions, stopping high taxes, stopping faked elections and so on.

Jose Martí (1853-1895), a poet, and passionate activist, also realized a reason why the fight for independence hadn’t succeeded was because the Cuban people themselves were divided, unable to find a goal to focus on, which resulted in growing tension between rebel leaders, weakening the rebel forces. Jose Martí is an important figure in Latin American literature, as well as the symbol of Cuban independence, dying in battle at Dos Ríos, Oriente province, at the beginning of the Cuban Revolution. General Maximo Gomez was on scene for this, the Battle of Dos Ríos, when the symbol of Cuban independence died.

Gomez, on top of his horse, in the jungle near the Contramaestre and Cauto rivers, with the sun shining overhead, surveyed his soon-to-be battlefield, the gears in his brain turning. After calculating the details, debating thoughts in his head, he came to a conclusion that the Spaniards had a strong position between palm trees, meaning his soldiers should remove themselves from the area. Perched on his horse, he called out his orders to the soldiers surrounding him: they were to retreat. As everyone rode away, Martí was left alone until a young courier, Angel de la Guardia, rode by, yelling out “Joven, ¡a la carga!” and for those of you not taking Spanish, it meant “Young man, charge!” Jose Martí, eager to make a difference, and not knowing any better, did just this. He leaned down a little, squeezing the horse with his boots, urging it to gallop forward, ready for battle, but with his black jacket and white horse, the Spanish spotted him immediately. He saw the Spaniard soldier raise his gun, pull the trigger, and before he had time to react, he had fallen off his horse. Angel de la Guardia, rather shocked, turned around to relay the news that their inspirational leader had fallen. This was a big blow to every rebel’s hopes and desires, but they continued to forge on.

Even with his unfortunate death, Martí remained a famous person in Cuba, and today has statues erected of him everywhere, even at Central Park in New York City.

Martí believed greatly in the idea of Cuban independence. He had poured his passion towards Cuban independence into his newspapers and articles. He felt that Cuba had its own character, personality, traditions, and ways of living that the Spanish did not, and therefore it made no sense that the Spanish government should continue oppressing the Cuban people. Along with finding the idea of Spanish controlling Cuba a stupid idea, he also disliked the Spanish because they failed to abolish slavery.

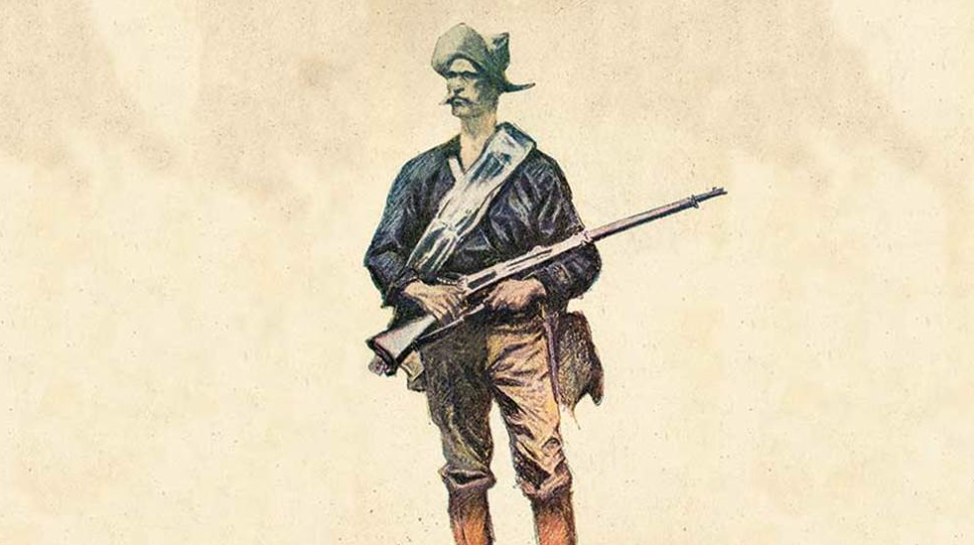

This third attempt at Cuban independence turned into the Cuban Revolution (1895-1898). In this revolution, the Spanish had the superior number of troops, and the Cuban generals used guerilla warfare (a type of informal warfare where small groups would try to ambush, or sabotage the enemy, usually a larger, more traditional military) to exhaust the Spaniards. General Maximo Gomez became the military commander in the Cuban Revolution. In the revolution, Gomez’s tactics included dynamiting passenger trains and torching the Spanish loyalists’ property and sugar plantations. He would not only kill Spanish soldiers, but also Spanish sympathizers, which though severe, greatly helped the outcomes of his attacks, but this brought an extreme reaction from Spain, which engaged in removal tactics which resulted in mass death. Gomez was greatly devoted to the cause and ended up helping the rebels for half of his life. However, his ruthless tactics provoked Spain to send in a butcher.

In 1896, Spain sent General Valeriano Weyler,

(1838-1930), feeling that he would be the one capable of stopping the rebellions in Cuba. He was in control of how Spain would restrain rebellions, and he decided the best tactic would be to separate the rebels and the rest of the Cuban population. The rural population of Cuba was gathered up into towns and cities that were guarded by Spanish troops so they could not help rebel causes. With these techniques he soon forced more than 300,000 civilians to leave their rural homes and into tight areas that greatly resembled concentration camps. Conditions were horrible especially in the hot, tropical climate, and many died from starvation and disease. In fact, the number of dead is estimated to be between 150,000-220,000 people, meaning that of all the people he gathered up, at least half would have died. With these shocking, inhuman acts (called removal tactics), U.S. newspapers started nicknaming him “The Butcher” and the American support for Cubans and the idea of their independence started to grow. Then finally in the last three months of this Revolution, the US decided to join, which started the Spanish-American War.

In the US, at the same time as Cubans were fighting for their freedom, Americans were developing new ideas, and reading their newspapers filled with yellow journalism. Yellow journalism is a type of journalism that does not follow the very important nine principles of journalism. They do not report what is going on, but instead the exaggerated version that catches people’s attention. Keep in mind that true journalism can only occur in democracies where there is freedom of the press: this true journalism is the Fourth Estate, responsible for keeping the other three branches of the government in line.

The first, and very important principle, is obligation to the truth, something yellow journalism does not have. Citizens need to have reliable and accurate facts, otherwise democracy does not work. This type of truth is “journalistic truth” (The Project for Excellence in Journalism, 2000). This is when journalists are creating “a fair and reliable account of their meaning, valid for now, subject to further investigation”. Transparency is key for successful journalism. It allows readers to make their own interpretations and assessments from the information they are receiving. Citizens have an ever growing need for reliable and verified information that is put into context, which brings us to another principle of journalism.

The third principle of journalism is a discipline of verification. Journalists need a professional way to verify the information that will be published. This does not mean that journalists are entirely free of bias, only that they have “a consistent method of testing information – a transparent approach to evidence”. This way of verifying information will allow them to produce work that is accurate and without their own biases. Examples of this type of verification can be finding multiple witnesses or asking all the sides to comment, again something that was not seen in 1898 with yellow journalism. This principle is what makes journalism stand out against many other types of communication. If journalism put only the exciting bits of news from one side that are very likely not true, how would citizens be able to make a correct assessment of the situation? These principles are very powerful, and when not followed, can lead to yellow journalism, and instead of journalists fulfilling a duty which is akin to being a part of culture, as in the Fourth Estate, they can poison the society they purport to serve.

Another important principle (though they are all important) is the second principle: loyalty is to the citizens. This means that even though news organizations are connected to things like advertisers and shareholders, journalists must hold their loyalty to the citizens above all else. This important commitment is critical to the credibility of their news organization. This commitment and allegiance means that journalists must paint a picture where everyone is represented, not just certain people. Their work cannot ignore specific citizens. The idea is that news organizations run on their credibility, so it is vital for them to hold this commitment to the citizens.

Now back to the 1890s. With the help of yellow journalism, which blows things out of proportion, many Americans felt that the Cubans were living under dire situations, and we had to step in. Yellow journalism would use huge headlines that were designed to catch people’s attention and increase the sensation and excitement. They usually contained little truth and a lot of exaggeration. Newspaper illustrations portrayed Weyler as the huge monster, Cuba as the poor damsel in distress, and the US as the hero who could swoop in and save everyone. With this, it’s no surprise that so many Americans felt the need to arrive in the mess and be the hero, or the Big Boy.

Another key point was when the USS Maine blew up. The USS Maine was a ship sent in January of 1898 to Havana, Cuba to protect American interests there. Unfortunately, a few weeks later, while anchored in the harbor, on February 15, 1898, the ship exploded. This explosion killed two-thirds of the crew, around 260 sailors who had been onboard, and riled the US population, propelling people’s opinions even farther that war was needed. In American newspapers, Spain was painted as the culprit even though there wasn’t evidence of them being so. Headlines would say “DESTRUCTION OF WARSHIP MAINE WAS THE WORK OF AN ENEMY” or, “CRISIS AT HAND SPANISH TREACHERY”. Even now, people aren’t sure what happened to the ship; some say ammunition in the ship got set on fire and it blew up – others that it was blown up by a mine though not directly linked to the Spaniards, and even others say that it was set on fire on purpose to provoke the American population. But whatever actually happened, the yellow journalism made it feel very much that Spain was the culprit, and this led to America declaring war on Spain only two months later.

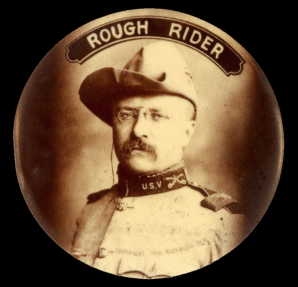

Now to understand what is to come, one has to first understand the very important, passionate, and courageous leader, the 26th president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt! Roosevelt had a rather bold nature. He was loud, and jumping at the thought of going to war and fighting with the Westerners, like the cowboys and Indians. As well as being slightly oblivious and maybe a bit too passionate, he certainly had spirit. He viewed going off to war as letting the world know that America is here and that we are willing to shed our blood and tears, going along with the concept of being a Big Boy nation.

As a young boy, Roosevelt was ill with asthma, but he soon overcame it, leading a very busy lifestyle, filled with his many interests instead. He was a lifelong naturalist, establishing many of our national parks, as well as a historian and writer, producing books such as The Naval War of 1812 in 1882. Then, his interests turned to politics, leading New York’s state legislature’s reform faction of Republicans. During this time, he experienced a devastating moment when both his mother, Martha Bulloch Roosevelt, and his first wife, Alice Hathaway Lee Roosevelt died on the same day! To deal with his loss he bought and created a cattle ranch in the Dakotas.

After recuperating, William Lafayette Strong (1827-1900), who won the 1894 New York mayoral election, offered Roosevelt a spot on the board of the New York City Police Commissioners, and no surprise, Roosevelt quickly became president of the board. During his time on this board, he met Stephen Crane, a phenomenal journalist and writer, who coincidentally also came to Cuba during the Spanish-American War.

They met at a literary club called the Lantern Club, and became good friends because of their interest in literature. Roosevelt even gave Crane special access to see the Jefferson Market Police Court for Crane’s newspaper pieces. However, their friendship went through quite some strain when Crane chose to testify on behalf of a friend, Dora Clark. Clark had been arrested for soliciting, and Crane testified as a witness to her illegal (he thought) arrest. But when Crane sent a telegram to Roosevelt, telling him what he was going to do in New York at court, feeling that Roosevelt would help insure he had “a square deal”, Roosevelt’s reaction was unexpected; he decided to “let the law take its course” instead. Roosevelt did this to save his own morals as well as his future political career. Even after the trial, many years later, Roosevelt still put a decent amount of space between himself and Crane. The friendship that had formed in a literary club was withering.

Following his time as president of the board of the New York City Police Commissioners, he became Assistant Secretary of the Navy under President McKinley from 1897-1898. After resigning to lead the Rough Riders, which is the period of time looked at here, he came back and continued his ambitious politician career. He was McKinley’s running mate in the election, and with Roosevelt’s hard work, they won by a landslide. After McKinely was assassinated, he became president at 42, getting the role of youngest president so far, beating John Fitzgerald Kennedy (1917-1963) by one year. As president, he did many notable things, including leading the construction of the world-changing Panama Canal, continuing to turn America into a Big Boy nation. At this time in his life (the beginning of the Rough Rider period), he had shed his younger, asthma-ill self, turning into a stocky man with slicked down hair, and eyes staring at you behind his pince-nez glasses (glasses that would pin your nose instead of the traditional ones that lie on your ears) with a competitive fire.

Even though Roosevelt led his troops, the Rough Riders with tactic and strength that day, he was never meant to be their leader. Leading up to the war, Russell Alger, the Secretary of War, offered Roosevelt a chance to be colonel in the First U.S Volunteer Cavalry, but doubting his abilities, he decided to request his friend, Captain Leonard Wood, to be appointed instead.

Roosevelt wanted to be lieutenant colonel, but his plans went off the rails when Wood got promoted, and Roosevelt had to move up and take charge, though I don’t why he had any doubts in himself in the first place! If you ask me, he did pretty well. It turns out, Roosevelt was going to be a leader despite his doubts.

Volunteers flocked in from all the areas in the West, riding on horseback with cowboy hats, ready for war. Others came in suits and shiny black hats: these were the well-educated men (mostly Ivy Leaguers) who felt they deserved to go to war. Yes, you heard me right. These men wanted to go to war – they felt they deserved to know hunger, dirt, honor and the feeling of courage which others before them had. They weren’t afraid of dying, no, instead they were afraid of being a coward. And they proved it that day on the hill that they weren’t cowards – far from it.

Loads of people came, ready to join the volunteer cavalry. They got on trains, said goodbye to family, and rode to their training site in San Antonio, Texas. Here, they trained, rode horses, learned how to fight, use a gun and how to kill. Because Roosevelt and Wood were able to train the men so well, unlike many volunteer groups, they went to Tampa, Florida on May 29, 1898, where they got ready to sail off to Cuba. On June 13, the group set sail for Santiago, Cuba, unfortunately without their horses. Even though they were a cavalry group, they had to walk into battles because the ship could barely carry the 17,000 soldiers that needed to be transported, much less the thousands of horses as well. Though most walked into battle, commanders, like Roosevelt, were able to bring their horses to Cuba.

The Rough Riders landed at Guantanamo Bay and joined up with the Fifth Corps. Here American forces claimed the vital harbor between June 6 and 10 (still under US control today), which though may not be mentioned a lot, was an important part of the war. After this victory, American forces continued to move farther inland.

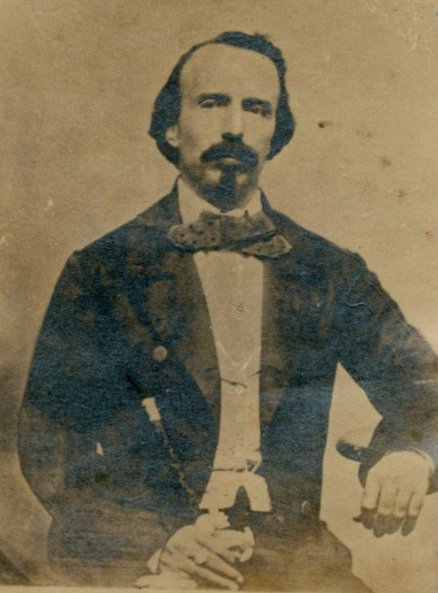

A week before the battle of San Juan Hill, American soldiers, led by Joseph Wheeler (1836-1906),

were going to get their first satisfactory taste of blood from the Spanish at the Battle of Las Guasimas, but at the cost of US casualties. Also on the American side was Demetrio Duany (1856-1922), a well-educated, Cuban man who had studied in France and the US. He was chosen by Calixto Garcia to confer and then act with the Americans. Against the large number of Americans, was Antero Rubín, a rather bald man who had volunteered to serve in Cuba at the age of 16. He was a successful leader on June 24, 1898, at this battle, where he made a bloody dent in US forces even though Spanish forces were small. In comparison, the Spanish did not suffer as many casualties as the US did. In the Battle of Las Guasimas the US lost 17 men, with another 52 wounded, while the Spanish only lost 7 with 14 wounded. Because of these unfortunate numbers, many historians later blamed Wheeler for wasting too many men in a frontal attack that wasn’t necessary. But at the time, because of our well known enemy, yellow journalism, Americans believed that the Spanish had suffered and we had won. Even with the number of casualties, both sides considered it a little victory. The US was satisfied, with confidence boosted after drawing the first blood. The Spanish felt that they had conducted a successful rearguard operation, guaranteed the safety of Rubin’s forces and moved away from the shore where there were threats from the large-caliber guns used by the US Navy.

And now, after climbing up and up on the roller coaster ride, we have arrived at the very top, the whole purpose of this article, what all the other pages were for: the Battle of San Juan Hill! You will get to experience Teddy’s passionate attitude which rippled through the U.S army, from the lowest ranks to the highest, seeing how many people sacrificed their lives for this decisive moment. So many questions must be brewing in your mind. Why did so many people die for this moment in history? What could this battle decide? What decisive actions did our men take that greatly affected history? As they say in elementary school, put your listening ears on, for you have a lot of details and key moments to learn about. Maybe even sit criss-cross-applesauce to get nice and comfortable for this leg of your journey.

West of Santiago, San Juan Hill and Kettle Hill were only a mile and a half away. Spanish leader Arsenio Linares chose to keep nearly all of his troops in this nearby city, only sending 760 out of 10,000 to San Juan Heights. No one knows why he did so, but he was clearly not anticipating such a major part of the war to be held at San Juan Hill, instead of Santiago.

General William Rufus Shafter (1835-1906) commanded the Fifth Army Corp, which was composed of three different divisions, with 15,000 troops in all. Jacob F. Kent (1835-1918) commanded the Corp’s 1st division. Henry W. Lawton (1843-1899) commanded the 2nd division, and Joseph Wheeler commanded the 3rd division, which was the dismounted cavalry division. Unfortunately, Wheeler ended up with a fever and had to turn command over to Samuel S. Sumner (1842-1937).

Shafter’s plan to attack was for Lawton’s division to move north at El Caney. Then they were to join the other two divisions to attack San Juan. Meanwhile, the other two divisions were to fight at San Juan. Sumner was supposed to be in the center, and Kent was to be in the south. Unfortunately, during the battle, Shafter was too ill from the tropical heat (whew!) to personally be there, so he set up headquarters at El Pozo, which is two miles from the hills, and communicated using mounted staff officers.

The Spanish troops (most of which weren’t at the hill voluntarily because they were conscripts, people that were forced to join) were in entrenchments that, while well concealed, were placed in such a way that made it difficult for the Spanish troops to return fire at the Americans. These trenches and fortifications were also placed at the crests of the hill, not at other strategic positions that could have been helpful in fighting off the Americans.

When Americans were under protection, or in defilade if you want to use the military term, it was difficult for the Spanish to hit them because of their position at the top of the hill (instead of other fighting positions). But luckily for the Spanish, once the Americans took the chance, and charged up the hill, they were out in the open, and great targets for the Spanish waiting at the top.

Now imagine if you will… the Spanish armed with their modern artillery, 7mm Mauser M1893 rifles with a high rate of fire and smokeless powders, walking back and forth in their fortifications, maybe even taking a break to “negligently gossip about the battle”.

As Crane said, “There was one man in a summer-resort straw hat. He did a deal of sauntering in the coolest manner possible, walking out in the clear sunshine and gazing languidly in our direction.” And then along with the people gossiping about the battle, there were Spanish artillery units with modern rapid-fire cannons. The Spanish were making a statement with all their weapons, for it was easy to fire at the Americans. All they needed to do was slide a round of gold cartridge shells in the rifle, turn the knobbed handle, and they were ready to fire. After each firing at the US soldiers, they could quickly turn the handle, dropping out the old shell, and they were ready to fire once more. They “fired a little volley immediately after every one of the American shells. It puzzled many to decide at what they could be firing, but it was finally resolved that they were firing just to show us that they were still there and were not afraid.”

Meanwhile, the Americans were making their way up the hill from both left and right, holding their bolt-action, smokeless Krag rifles. From the far left, there was the 6th, 9th, 13th, 16th, 24th, and 10th infantry and from the far right there was the 3rd, the 9th and 10th colored cavalry, also called Buffalo Soldiers, and the 1st volunteer cavalry, which has become known as the Rough Riders.

The Rough Riders ran up Kettle Hill on foot, gripping their Krag rifles tightly with their hands, sweat running down them, from both the intense heat and nerves of having 100 Spanish soldiers, with Mausers, shooting eagerly at you. The US troops, in their beiges and blues, seemed to be dropping left and right, bullet wounds in arms, legs, chests. Any second, it could be you lying on the battlefield in despair.

After a hard fight up the hill, the Rough Riders along with the 9th and 10th cavalries made it to the top of Kettle Hill, taking over the Spanish. Soon after this success, the other infantries took over San Juan Hill, and the whole area turned from Spanish to American rule. The Americans looked over at Santiago, and the next day started a siege on the city.

Before we bring this essay to an end, there is one point which Crane mentions, that I found interesting and would like to point out. In Crane’s writing, he discusses how the Cubans did not contribute a lot at the battle of San Juan Hill. He says that they did nothing, only to eat the food provided for them or beg for a favor. He says US soldiers thought they would be fighting with an ally but found that it wasn’t the case. “In the great charge up the hills of San Juan the American soldiers who, for their part, sprinkled a thousand bodies in the grass, were not able to see a single Cuban assisting in what might easily turn out to be the decisive battle for Cuban freedom.” He continues: “The average Cuban here will not speak to an American unless to beg. He forgets his morning, afternoon or evening salutation unless he is reminded. If he takes a dislike to you he talks about you before your face, using a derisive undertone.”

Crane also points out, if “he stupidly, drowsily remains out of these fights, what weight is his voice to have later in the final adjustments? The officers and men of the army, if their feeling remains the same, will not be happy to see him have any at all.” Perhaps, this connects to the communism that we still see on this island. After all, their freedom, which Americans fought for, only lasted 40-50 years. Maybe the Cuban voice could have been stronger at San Juan Hill, which, who knows, could have affected them now. But, Cuba still has hope. Martí is hovering over them, his spirit in the statues, reminding the people that in the future, Cuba might not be such a communist country.

Jason Qin responds:

The Spanish-American War, in which America collects Spain’s life insurance, is an impactful war for all three parties involved, as it sparked the USA’s evolution from adamant neutrality to global superpowerdom, buried Spain’s empire after the start of its centuries-long decline with the defeat of the Spanish Armada, and birthed a shaky yet independent Cuba which would bring communism to America’s doorstep, but it was a relatively short conflict and the buildup is honestly more interesting than the conflict itself; the buildup being the decades-long fight for Cuban independence and the ideas that drummed up US popular support for the war. It was really great that you included all of this background to help your reader truly understand what the Spanish-American War is all about, even if your original goal was to cover a battle.

Your covering of the Cuban path to independence was a valiant effort, for it is complex. Then, when you get to the causes and ideas that drummed up US popular support for the war, we can get at least a beginner’s appreciation of the complexity that gave rise to the Spanish-American War; and as I am about to start writing my own Battles essay, I have an expanded sense of appreciation for the demands put upon the historian: context is (almost) everything.

In other words, you wrote of the Cuban intellectuals who spoke of independence while it was the Americans who got the job done. It is also America’s interference with something that is, in the end, none of their business (the frontier thesis had little practical application for the US post-Westward Expansion) which makes it all the more interesting. Or it may be interesting to point out the irony in Americans aiding Cuban independence, which disallowed Cuban strength to form in its own right, and that in the 1950s, all of this evaporated under the Castro and Guevara takeover… in that if you interfere with an adolescent’s growth, you may permanently weaken that stripling.

Firstly, you touched on Jose Martí, the wars and uprisings preceding the Spanish-American War, and how the system to prevent American bellicosity was breached, as with “yellow journalism, which blows things out of proportion, many Americans felt that the Cubans were living under dire situations” and it infected people’s minds, especially with its coverage of the explosion of the USS Maine.

After that, you move into the war where again, yellow journalism played a role, convincing the people that “the Spanish had suffered and [the Americans] had won” at the Battle of Las Guasimas. Then, you move on to your focus, the Battle of San Juan Hill (I actually forgot I was reading a Famous Battles essay when I read your essay up until this point). It’s clearly a mess, with problems arising on both sides which proves my point that the Spanish-American War is mostly interesting for its prelude and aftermath (honestly, there’s enough material here for a paper on just those two topics).

There are a few things that I wished you did with this essay. First off, since your title is about America becoming a “Big Boy Nation” or in other words, an imperial power, it would have been nice to just acknowledge exactly what that meant for the nations under imperial control in the 20th century, as people can and will argue imperialism’s negative effects like the role it played in forming the Third World; on the other side, the reader might expect that you at least give some hinting at the decisive role USA would play in the World Wars as it threw around the weight of its Big Boy-ness on a more global stage. Also, I would have liked it if you briefly expanded on what exactly happened during “[Cuba’s] freedom, which Americans fought for, only lasted 40-50 years,” and how the nation was plagued with instability and overall horrible timing. I’m curious if you’ve read the 2019 Constitution which states that the people of Cuba are guided by the “ideal and example of Martí and Fidel [Castro]”? (You stated that “Martí is hovering over [Cubans].”) By combining Castro and Martí in their Constitution, do you still believe that “Cuba still has hope”? Even when their supposed savior’s ideas are already being applied yet contaminated with that of Castro’s, can they still rely on the spirit of Martí’s teachings to dig them out?

Regardless, you thoroughly covered the Spanish-American War, dipping deep into the ideas and intellectuals of the Cuban Revolution whilst also capturing the political climate and attitude of the USA during the 19th century, setting the stage for the famous battle in question and then closing off by touching on the tragedy of Cuba, one of many nations crippled by circumstance and misfortune and entranced by the siren song of Marxism.