Eudora Welty’s Revision Process: Exploring the Two Versions of “Flowers for Marjorie”

“We grew up to the striking of clocks.” Thus begins Eudora Welty’s One Writer’s Beginnings, a book that was on the New York Times Bestseller List for 44 weeks in the early 80s. Welty transports us into her earliest memories, retracing her path to becoming one of our nation’s most legendary authors. The chimes of her family’s collection of clocks in their house on North Congress Street in Jackson, Mississippi, was a regular metronome in her daily life. Welty and her brothers became “time-minded” which “was good…for a future fiction writer, being able to learn so penetratingly, and almost first of all about chronology.” Along with the clocks, Eudora Welty’s father Christian Webb Welty supplied his children with other bells and whistles all stored in a drawer in the library table: “a telescope with brass extensions, a folding Kodak that was brought out for Christmas, birthdays, and trips, a magnifying glass, a kaleidoscope, and a gyroscope.” Through these instruments, Welty and her brothers grew up with a sense of wonder for the world.

Simultaneously, her mother Chestina Andrews Welty gave her the gift of literature. Mrs. Welty would read to her daughter in the rocker, “which ticked in rhythm.” Welty loved stories so much so that she was shocked when she found out that “story books had been written by people, that books were not natural wonders, coming up of themselves like grass.” The Welty home was overflowing with books: encyclopedias and dictionaries, John L. Stoddard’s lectures that indicated Mr. Welty’s “longing to see the rest of the world,” the Victrola Book of Opera, Jane Eyre, and Sanford and Merton (a best-selling children’s book by Thomas Day). In addition to her family library, Welty accessed the Jackson Carnegie Library. Her mother gave her a library card and allowed her to pick out any book, children or adult. Welty checked out books, “two by two,” per the frightening librarian Mrs. Calloway’s rule, “as fast as [she] could go, rushing them home in the basket of [her] bicycle.”

As a child, Welty felt the “secure sense of the hidden observer.” She would listen to her parents’ discussions in the dark lit room. This skill mimics that of reading: regardless of how immersed Welty, or any reader, felt in the story’s plot, she could only watch the characters grow and the events unfold from a distance.

There was no “avid curiosity” to find out her parents’ secrets. Just the three of them in one room was enough for her; that was “the chief secret,” lying in bed with her “fast-beating heart as “the two of them, father and mother, [sat] there as one.” One secret that Welty did actively seek was: “where do babies come from?” In provoking this question, she discovered the death of her mother’s first child who would have been her older brother. This was an accident – younger Welty had been rummaging through her mother’s drawers when she came across a small box containing two delicately wrapped buffalo nickels. She eagerly ran to her mother to ask to spend her findings, but her mother, appalled by the idea, refused to give Welty the nickels no matter how much she begged. These nickels belonged to Welty’s late older brother, the ones that had lain on his eyes and were Welty’s mother’s last physical connection to him. He died because she herself was also dying, and while the nurses cared for her, they nearly forgot about him, Welty’s mother explained. However, her mother had “told [her] the wrong secret—not how babies could come but how they could die, how they could be forgotten about.” As Welty reflects on this moment, she realizes that “the future story writer” in her younger self must have unconsciously noted that “one secret is liable to be revealed in the place of another that is harder to tell, and the substitute secret when nakedly exposed is often the more appalling.” What secrets has Welty omitted in her stories? And in particular, in “Flowers for Marjorie”’s two versions, is there a substitute secret that can be understood as more appalling in one version than the other?

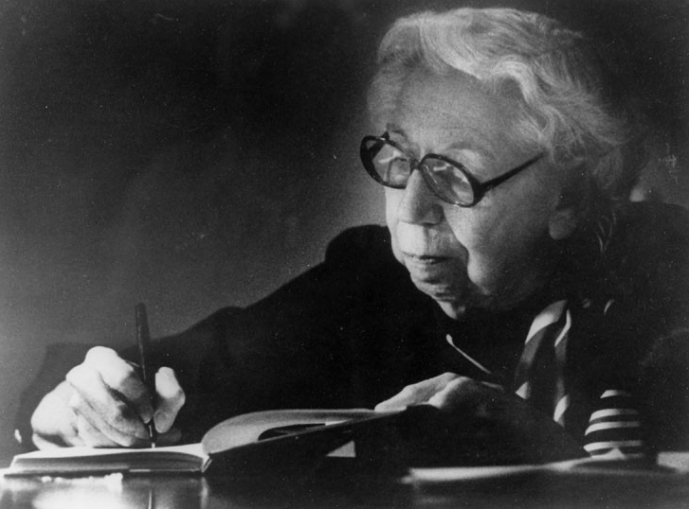

Born in Jackson, Mississippi, in 1909, Welty lived there for most of her life with her parents, Christian and Chestina Welty, and her two brothers. Her father’s interest in small gadgets inspired her love for machines like cameras, while her mother nurtured her love for reading. In college, Welty studied English literature and, at the suggestion of her father, advertising. After graduating, she returned to Jackson where she worked at a local radio station and wrote for the Memphis newspaper. In 1936, Welty became a full-time writer, having “The Death of a Traveling Salesman” published in the Manuscript literary magazine. The editor of Manuscript called it “one of the best stories we have ever read.” In 1941, Eudora published A Curtain of Green, a collection of short stories including “Why I Live at the P.O.” and “A Worn Path.” Later, her novel The Optimist’s Daughter (1973), received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

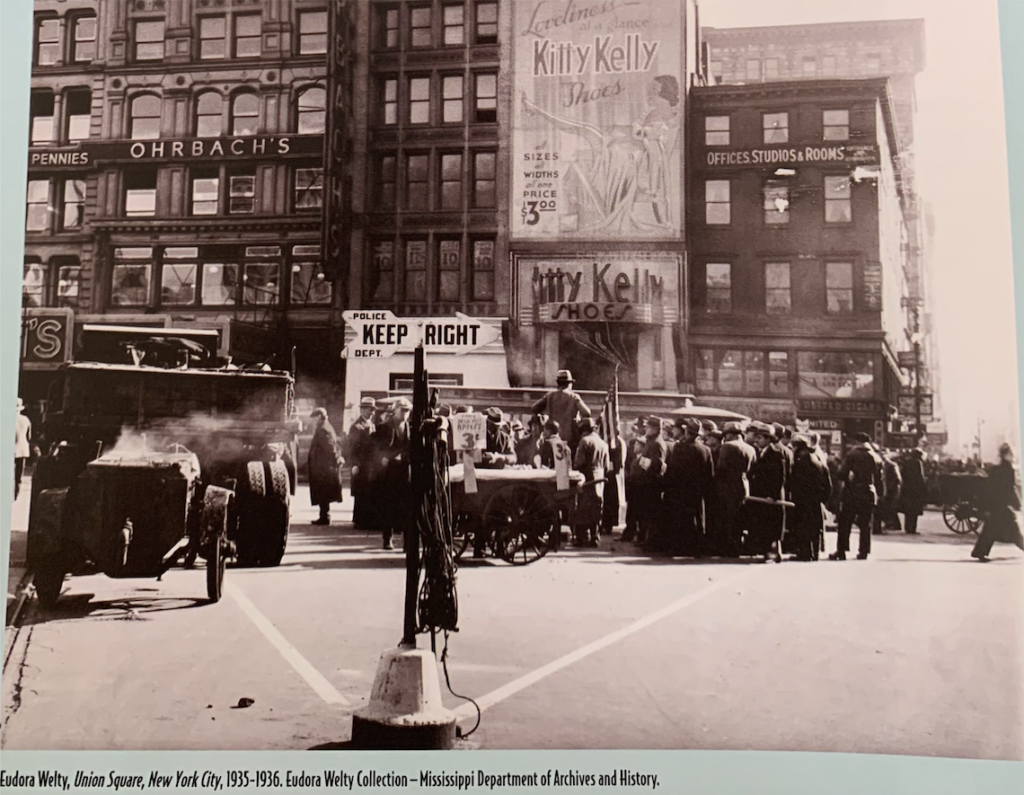

Along with her distinguished writing career, Welty was an avid photographer. In 1933, she worked for the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Collecting stories, interviewing, and photographing people’s daily lives allowed her to gain a deeper insight into Southern life. She continued photographing until the 1950s. Collections of her photography were published in One Time, One Place and Photographs. Her experience as a photographer evidently influenced her writing process. She states in One Writer’s Beginnings: “Getting my distance, a prerequisite of my understanding of human events, is the way I begin work.” In photography, distance determines “frame, proportion, perspective, [and] the values of light and shade.” In writing, this distance establishes the relationship between the reader, the characters, and the author. Distance sets the reader’s perspective of the characters and dictates the reader’s perception of the story’s plot.

Determining distance is not only crucial at the beginning of the writing process but also during revision; the author must step back from their writing to make sure that the distance is right. Overall, though, she keeps the reader in her mind while writing, Welty truly writes for “it, for the pleasure of it. [She believes] if [she] stopped to wonder what So-and-so would think, or what [she’d] feel like if this were read by a stranger, [she] would be paralyzed.” Of course, she valued what her friends and family thought, and she could only rest after they had read the work. During the writing process, however, she tells herself, “I have to just keep going straight through with only the thing in mind and what it dictates.” The obvious unanswerable question is: what is it? What is this thing that Welty wrote for?

In one of the most difficult short stories I’ve ever read, one that borders on bringing a gagging sense of abomination to the reader’s mouth, “Flowers for Marjorie,” there are two extant versions that vary wildly from each other. This story, depicting a cold-blooded murder of a pregnant wife, is to some critics, outside of Welty’s canon, outside of her normal range of subjects, and outside of any perceptible redeeming quality. Yet it is worthy of attention for we glimpse Welty’s possibly equally unpleasant process of revisiting and revising, though one that she clearly deemed necessary. From Schooner’s “he realized that he had not acted at all: the pansy still blazed on the coat” published in 1937 to the Collected‘s “slowly he realized that he had not acted at all, that he only had a terrible vision” published in 1941, from “he sank back on the couch trembling with the desire and the pity that overwhelmed him and said harshly” to “he threw himself on the pillow and said harshly,” we have strong and easily observable edits and changes. But what was Welty’s aim in all of this? What demonstrable effect do the two versions of this deadly and dreary psychological portrait have?

The earlier version in the Prairie Schooner begins slowly, describing the one movement of Herman blinking his eyes in two full sentences: “Herman’s eyes blinked when the pigeons whirled suddenly as though a big spoon had stirred them in the sunshine. He closed his eyes upon their flying opal-changing bodies, and opened them lowered to the sidewalk.” Welty then pans down to Herman’s shoes, a scene that is absent in the later version. There is a hole at the bottom of one of his shoes, wearing through his sock as well, that had expanded since the morning, a sign of his efforts at finding a job to support his expectant wife Marjorie and their future family. However, when Howard returns to their apartment, Marjorie’s slightest suggestion of finding work to earn money to support their baby causes him to erupt into hysteria. Marjorie says weakly, “Maybe you could find work before then, Herman… that would mean we could scrape ten dollars a month out of that to pay a nurse, maybe, for a little while afterwards, after the baby comes.” Herman scoffs at the idea: “I—I just don’t believe it; they won’t give me any work. Think about that—getting up early in the morning—the alarm clock would ring every day—eating breakfast—running to work—steady—every day—”. Herman’s words dominate Marjorie’s, whose figure seems to shrink into a corner. Later, when Herman kills Marjorie, his hatred for change, work, and being controlled by time and the presence of the baby seem to incite his act. Every time I read this scene, I am shocked over and over again. How can someone kill their pregnant wife?

The Collected version features a distant view of Herman, now named Howard, and a bossier and more strong-willed Marjorie. Welty begins this later version with, “He was one of the modest, the shy, the sandy-haired—one of those who would always have preferred waiting to one side.” (The Schooner version reads, “Herman’s eyes blinked when the pigeons whirled suddenly as though a big spoon had stirred them in the sunshine”.) As opposed to the close-up on his eyes blinking and the hole at the bottom of the shoe from the Schooner, the readers now view Howard from afar, blended in with the other sandy-haired guys, having no particularly distinct features. Welty establishes our first impression of Howard, someone who would never think (“[he] always preferred waiting to one side”) of killing his pregnant wife. The police officer at the end of the story doesn’t recognize Howard as someone unique either, referring to him as “the nondescript, dusty figure with the wide gray eyes and the sandy hair.” In this version, the cause of Marjorie and her baby’s death may be Howard’s reaction to Marjorie’s words. Unlike the passive and timid woman she is in the earlier version, she says to Howard in her tender-yet-bordering-on scolding voice, “I expect you can find work before then, Howard.” This tone could tick anyone off. Does Welty purposefully make Marjorie more bossy to justify Howard killing her? We further sympathize with Howard when he expresses that “Just because you’re going to have a baby… doesn’t mean that I will find work! It doesn’t mean we aren’t starving to death.” The anxiety of becoming a new father overwhelms Howard.

Despite the tense dynamics between Howard and Marjorie, Welty emphasizes that Marjorie is Howard’s home, his pillar, especially and tragically, after her death. In the first version, Herman rises from his bench in the park to return to “the room” while in the later version, he “[starts] back to her.” In the Collected version, Welty also adds a sentence about the differences between the “dark, nervous, loud-spoken women” in New York City and the women in Victory, Mississippi that were all “like Marjorie—and that Marjorie was in turn like his home.” However, the physical distance that separates them reveals their strained relationship: Howard could only “stare at her…[and] look at her.” Even when he approaches her, sits down next to her, and leans into her arms, he feels her “time-marked softness and the pulse of her sheltering body.” Why does Welty use the adjective “time-marked”? After Howard kills Marjorie, he seems to lose his sense of time and place and walks aimlessly around the city. Had Welty ever created a character so bereft of knowledge of the fundamental ticking of clocks? From standing in front of the window of a trinket store, Howard suddenly seems to teleport and “[finds] himself in the tunnel of a subway” without knowing how he got there. At the end of the story, when Howard confesses his horrific actions to the police, both the policeman and Howard seem to lose their sense of place and time even though “the street-intersection sign was directly over their heads, and in the air where the pigeons flew the chimes of a clock were striking six.”

Through reading Welty’s short stories, whether it’s “Flowers for Marjorie” or “The Wide Net,” we trace the twists and turns of Welty’s mind by following her creative choices. How and why does she make the decisions that she does? As the writer, she dictates the story’s direction, yet perhaps she also lets the story itself dominate at times, allowing it to flow freely and naturally. Her short story “The Wide Net,” in particular, demonstrates the characters, William Wallace and his crew of men, taking over and leading the story in their languid expedition to find William’s missing pregnant wife, Hazel.

“The Wide Net” has a very loose plot, which allows the reader to luxuriate in the deep cadences of the South, and we can get a sense for how Welty’s mind, like a roving camera, searches through to find special moments. Why did the following moment make it to the final revision of “The Wide Net”? Is it integral to the plot? William Wallace and the crew of men launch into their mission to find William Wallace’s missing wife Hazel. As the search party follows the Old Natchez Trace to the Pearl River, they arrive at a high ridge where they can see the train rumbling in the distance. The Rippen brothers, Grady and Brucie, stop in their tracks as Grady counts the cars to himself and Brucie watches his brother’s lips, “hushed and cautious, the way he would watch a bird drinking,” until tears come to Grady’s eyes. Welty explains why the tears come: “it could only be because a tiny man walked along the top of the train, walking and moving on top of the moving train.” During my first reading of the story, this scene was difficult to comprehend: why does Grady tear up after seeing a man on the top of the train? Perhaps Grady imagines this unknown figure to be his father who, as Welty previously mentioned, drowned in the Pearl River. But she states that it can “only be because…”. Grady’s eyes are tearing up because he is squinting so hard that he can see the man on top of the train from several miles away. We usually relate tears to emotions such as sadness and grief and occasionally happiness and joy, but Welty reminds us that our eyes water for other reasons too.

William Wallace’s dawdling journey in “The Wide Net” with various detours inspired my own short story, “The Herbalist.” The midwife Hilda and her trusty herbalist Rosie are called in to facilitate a safe birth, and Rosie forgets to bring an essential herb. Hilda orders Rosie to fetch it from the wild, but nature entrances Rosie and reels her in, causing her to lose track of time and nearly not to be able to find the herb. While writing this story, I tried an out-of-order technique that Welty describes as using pins: to “[put] things in their best and proper place, revealing things at the time when they matter most. Often I shift things from the very beginning to the very end. Small things—one fact, one word—but things important to me. It’s possible I have a reverse mind and do things backwards, being a broken left-hander. Just so I’ve caught on to my weakness.” I began writing the story with the two ladies on the road, driving to their client Janet’s house, not knowing that this scene would actually come later in the story’s sequence of events. This scene establishes the dynamic between the two protagonists, as Hilda is driving and demands Rosie to give her directions while Rosie is sprawled in the passenger seat sound asleep. I wrote the character exposition after finishing the scene where Hilda and Rosie arrive at Janet’s house. With Rosie and Hilda already alive and on the page, I found it easier to write in a way that would introduce these characters to the readers one by one.

Revision is a part of writing, though revising a published work is rare. Welty even states: “When it’s finally in print, you’re delivered—you don’t ever have to look at it again. It’s too late to worry about its failings.” We as readers may never know why Welty revised “Flowers for Marjorie” after publishing it to Schooner. Her decision defied time and circumstance, and seemingly for once, she was unable to refine the story’s jagged edges, its confusing chronology, leaving us to assimilate its seeming crudity.