Milo Yiannopoulos: The Division of Discourse

Milo Yiannopoulos was an editor at Breitbart, an alt-right magazine, before his resignation. An extremely publicized speaker for the alt-right (a group who reject mainstream conservatism and who themselves are rejected by such leaders as John McCain, George W. Bush, and Mitt Romney) and an outspoken supporter of then-presidential candidate Donald J. Trump, Milo continues to give speeches on college campuses across the US, those where he is not violently protested. A strong presence on Twitter, he gained even more notoriety – fame for actions that the general public looks down upon – when his inflammatory remarks were perceived as racist, which prompted Twitter to permanently ban him. Milo denounced Twitter as cowardly and declared himself a martyr for free speech, prompting his followers to rally behind him; #FreeMilo went viral. Only a few months later, in early 2017, UC Berkeley cancelled Milo’s speech due to violent protests by Berkeley’s Antifa, a violent anti-fascism group. Antifa members dedicate themselves to fight against fascism, and are known to wear balaclavas as they smash store windows and clash with cops.

On July 11, 2016, the remake of Ghostbusters was released. It featured Leslie Jones as “Patty”, an MTA employee-turned-Ghostbuster, a sassy African American mainlining the raw terror of dealing with the supernatural. In the week after the film’s release, July 18, Jones received tweets perceived as racist, many of which likened her to a gorilla or contained racist terms. Milo joined in the fray with a meme of a Ghostbusters’ emblazoned Twinkies package: “I can’t imagine what Sony’s marketing department was trying to tell us about fans of the new feminist Ghostbusters.”

Milo’s meme appeared on the 18th at 1:08 pm EST, and was followed by a 4:18 pm EST tweet promoting his review of Ghostbusters (2016). His alleged harassment began at 5:54 pm EST when Milo tweeted, “If at first you don’t succeed (because your work is terrible), play the victim. EVERYONE GETS HATE MAIL FFS”. Calling Jones out for self-victimization, Milo continued his mockery of the remake. A provocateur, he takes insults in stride, expecting others to react the same. Milo accused the Ghostbusters marketing team of deploying Jones to play the victim because the movie was doing poorly, and called her barely literate for her grammatically poor tweet: “@Nero [Milo’s Twitter handle] you have been reported I hope the lock your Acct”. Jones tweeted screenshots of the perceived harassment, with “sad”, “so sad”, or “reported”, in some captions. The timestamps on these screenshots show that they were sent between 6-7:30 pm EST. He then shared a screenshot showing that he has been blocked from her Twitter page. The next day, Milo posted screenshots of racist remarks allegedly tweeted by Jones; many of her followers disputed their provenance. Milo was banned later that day, on July 19.

Milo’s supporters fought the ban. They tweeted screenshots of old tweets from Jones. One was in response to Skrillex’s Grammy Award for Best Dance/Electronic Album: “get… outta here a white boy is best dj wtf?”. The question some asked was: isn’t this racism? How can this woman get away with such a boldly racist statement? Are Twitter’s moderators doing their jobs evenhandedly? Although the Skrillex comment was from 2012, the only visible responses today are from July and August 2016. What happened to old responses? Did Twitter edit them, to cover for Jones? Are we expected to think no one responded to the original mini-screed on Skrillex’s award? Reactions are therefore limited to the discourse after Milo’s ban. From July 20th, 2016: “Another hateful, racist tweet by a blatant racist. I’m reporting this.”

Both sides sling insults or threaten tattling as children do, yet only Milo is banned. Twitter users took note: “Wow well, i did respect you for a while atleast [sic] until i found out you were a hypocrite.” Jones also employed animal imagery – a tweet containing an image of a hippo alongside Caucasians in a partially-submerged car, with the words: “White folks!” A comedienne, she toys with her observations, pointing out the inadvisable decisions white people make. But is it a joke, or is it a remark similar to the gorilla slur? Whatever the case, Milo supporters interpreted the image and caption as racist, and responded in similar fashion. One user posted an image of monkeys climbing over a car juxtaposed with black rioters standing on a police car. Milo had allegedly broken Twitter’s rules, but they argued that Jones had too; she tweeted “Get her!” in response to a hateful tweet, directly inciting harassment on another user whose account is now protected (visible only to select users).

Whatever the case, Milo supporters interpreted the image and caption as racist, and responded in similar fashion. One user posted an image of monkeys climbing over a car juxtaposed with black rioters standing on a police car. Milo had allegedly broken Twitter’s rules, but they argued that Jones had too; she tweeted “Get her!” in response to a hateful tweet, directly inciting harassment on another user whose account is now protected (visible only to select users).

Roughly two weeks after Antifa’s rage resulted in Milo’s event cancellation, William Jelani Cobb contributed an article to The New Yorker. Cobb, born August 21, 1969, is a professor of Journalism at Columbia University, and formerly an associate professor of history, and director of the Institute for African American Studies at the University of Connecticut. Moving from the South to Queens to provide their children with a better education, Cobb’s parents saw their son attending Howard University in Washington, D.C., where he first began his writing career with One, a short-lived periodical; he then moved on to the Washington City Paper. During this time, Cobb found a deep interest in racial issues and added “Jelani” (meaning “powerful” in Swahili) to his name to connect with his African tradition. Cobb demonstrates his interest in race, writing on current racial issues, and is a staff writer at The New Yorker.

contributed an article to The New Yorker. Cobb, born August 21, 1969, is a professor of Journalism at Columbia University, and formerly an associate professor of history, and director of the Institute for African American Studies at the University of Connecticut. Moving from the South to Queens to provide their children with a better education, Cobb’s parents saw their son attending Howard University in Washington, D.C., where he first began his writing career with One, a short-lived periodical; he then moved on to the Washington City Paper. During this time, Cobb found a deep interest in racial issues and added “Jelani” (meaning “powerful” in Swahili) to his name to connect with his African tradition. Cobb demonstrates his interest in race, writing on current racial issues, and is a staff writer at The New Yorker.

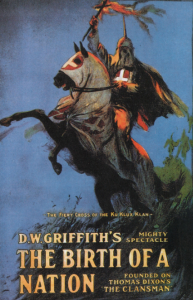

In the article, Cobb leans on history: he contextualizes the controversy with U.S. racial relations and struggles. Though the corollaries are not precise, he seems to think the optics are at least convenient: Cobb frames the Milo and Antifa/Berkeley struggle with D.W. Griffith and William Trotter. Co-founder with W.E.B. du Bois of the Niagara Movement (which aimed to move away from Booker T. Washington’s more passive resistance), and publisher of his own activist newspaper, The Guardian, Trotter was particularly opposed to D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (a movie some claim glorified and revived the Ku Klux Klan). He organized Boston-area protests that ran to riot on some occasions. In an attempt to bar the distribution of Griffith’s film in Boston due to its alleged racist content, Trotter found himself fighting the nascent film arts community, and promoting censorship which conflicted with the freedom of speech that allowed him to publish his newspaper. It’s interesting to note that at the time of the film’s release, the great American social worker Jane Addams (of Chicago’s Hull House) said this: “One of the most unfortunate things about this film is that it appeals to race prejudice upon the basis of conditions of half a century ago, which have nothing to do with the facts we have to consider to-day. Even then it does not tell the whole truth. It is claimed that the play is historical: but history is easy to misuse.”

(a movie some claim glorified and revived the Ku Klux Klan). He organized Boston-area protests that ran to riot on some occasions. In an attempt to bar the distribution of Griffith’s film in Boston due to its alleged racist content, Trotter found himself fighting the nascent film arts community, and promoting censorship which conflicted with the freedom of speech that allowed him to publish his newspaper. It’s interesting to note that at the time of the film’s release, the great American social worker Jane Addams (of Chicago’s Hull House) said this: “One of the most unfortunate things about this film is that it appeals to race prejudice upon the basis of conditions of half a century ago, which have nothing to do with the facts we have to consider to-day. Even then it does not tell the whole truth. It is claimed that the play is historical: but history is easy to misuse.”

According to Cobb, Antifa also faced this conundrum, using their freedom of speech to suppress someone else’s. Is this allusion fair? It can be difficult to censor artists and thinkers, and we know that D.W. Griffith’s subsequent film was entitled Intolerance, whereby he addressed the reactions to The Birth of a Nation. In Berkeley, the Antifa organized a black bloc to disrupt a peaceful protest of nearly 1,500 students. A black bloc, a term first coined in the 1980s, refers to a mob dressed in black that attacks police and storefronts in a hit-and-run style. The Berkeley Antifa black bloc caused over $100,000 in damage on the campus and another $400,000 to $500,000 in damages in the surrounding city, forcing the university to cancel Milo’s speech due to safety concerns.

Antifa silenced Milo, and Cobb reprimands them: “the black-clad rioters among the protesters at Berkeley who prevented Yiannopoulos from speaking… served his ultimate interests.” What are the ultimate interests Cobb intimates? Damage to property? Expressions of rage, anonymous and inchoate? Or is it fame for fame’s sake? Perhaps a bigger platform with which to call names and be “racist” or “sexist”? Cobb identifies Milo’s actions on Twitter unequivocally as “racist, sexist harassment”, and when Milo, after being banned, calls the social media platform “a no-go zone for conservatives”, Cobb writes that this is a “tacit admission”:

“The tacit admission that Yiannopoulos sees targeted abuse of a female African-American comedian as ‘conservative’ is revealing, if only in that it strips away the fig leaf of euphemism separating the alt-right from the hive of racism and sexism that defined last year’s Presidential election.”

In a sentence, Cobb strips away his own fig leaf, revealing a shallow tendency to lump party and partisan rancor with only one side. His calcified opinion of Milo leads him to assume the worst and expect the least.

Does Cobb have a hardened opinion about Milo’s being able to add to discourse, and does that cloud his sight of the potential value of dissent? Does he disagree with Antifa in principle? Evidently not. He states that there is only “a fig leaf of euphemism” between the alt-right and the “hive of racism and sexism” that is known as “conservat[ism]”! He then blames this “hive” for the 2016 election’s tone. He ignores the fact that it takes two to tango, and misguides the readers of The New Yorker so that they can blame and ostracize roughly half of the American electorate. Deplorables anyone? Is this a rhetorical confit? Simmering in his own internal bias, he then seals off opportunity for discourse, shrouding the important topic with an analogy: “No chemistry department would extend an invitation to an alchemist; no reputable department of psychology would entertain a lecture espousing phrenology”. The analogy does not hold; the Berkeley College Republicans are a club, not a department. It is reductive and unhelpful.

Cobb reprimands Antifa only for their methods, but endorses their shallow views and double standards. The rioters lay siege to UC Berkeley, a school known for its liberal thinking that was very tolerant in hosting Milo’s speech. Antifa was misinterpreted as the voice of the people. The fact that Antifa are black bloc and disguised was not clearly conveyed by the media, and Berkeley became the one to blame. Is it any surprise that Milo benefitted from the cancelling of his event, “declar[ing] himself a martyr for the cause of free speech”? He mobilized his followers and drew attention to what the great modern dancer Isadora Duncan called “the height of vanity”: censorship. In his unconscious and ill-expressed allegiance to Antifa, Cobb cries crocodile tears and muddles our understanding of what the event symbolizes.

Cobb’s slapping Antifa on the wrist is hypocritical:

“The further fact of Yiannopoulos’s fervent support for President Trump is not, then, surprising. Few figures in American history have better weaponized the imaginary grievances of entitled people who consider themselves oppressed than Trump has.”

By reprimanding Antifa for closing the door on Milo’s right to free speech, or by grieving the fact that Milo attained more fame because of the botched protests, Cobb is playing to one side. But out of the same mouth, almost in the same rhetorical breath, he calls Trump’s (and his supporter’s) grievances ‘imaginary’. One grievance of the ‘entitled people’, which Cobb deems imaginary, for example, could be illegal immigration. If Cobb met a parent of a son or daughter who had been killed by an illegal immigrant, especially one who had been given ‘sanctuary’, could he state to their face that their loss is imaginary? Why does he use such sweeping generalizations as “entitled” and “imaginary”? What’s the purpose?

He evidently does not accept conservatism in any form, and we must assume he is not open to discourses that challenge the liberal status quo. Accordingly, he influences his readers’ opinions of Milo by dismissing conservatives throughout the article: they have “imaginary grievances”, are a “blinkered tradition”, and act out a “rendition of victimhood” that passes as the real thing. Milo spews a “toxic brew of bigotry” that implies his lack of “credibility”. To Cobb, the conservatives continue to exist solely because of precedent and their invalid arguments prove their outdated existence. A self-proclaimed “virtuous troll” or “troll for Jesus (in itself a troll)”, Milo perhaps has unveiled the hypocrisy he sees in the media.

The current debate regarding free speech tends to center as much on those potentially affected by what is being said, as on the rights of those making alleged offensive statements. Cobb may be trying to demonstrate this through the structure of his article – he empathizes with yet reprimands the rioters of the Berkeley speech, but essentially disparages Milo and the Conservative movement.

Milo resigned from Breitbart News on February 21, 2017, where he had worked as an editor and written articles. A scandal emerged from a year-old video of him allegedly condoning pedophilia. He resigned with his first public apology and made it clear that he does not condone pedophilia, citing his poor wording, British sarcasm, and editing as the cause for the misinterpretation. He also stated that he is a victim of abuse. To Milo, the scandal was forced by a “cynical media witch-hunt” designed to cripple him and discredit him. He resigned to relieve his employer from the media noise surrounding the gaffe; he is grateful for the platform Breitbart has provided him, and which he has outgrown:

“I would be wrong to allow my poor choice of words to detract from my colleagues’ important reporting, which is why today I am resigning from Breitbart, effective immediately. This decision is mine alone.”

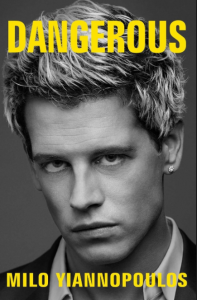

The scandal also lost him his $250,000 book contract with Simon & Schuster and his invitation to speak at the Conservative Political Action Conference. Milo states: “My full focus is now going to be on entertaining and educating everyone, left, right and otherwise”. Milo’s book, Dangerous, was released on July 4th, 2017, published by his newly started publishing company Dangerous Books. Days later, on July 10th, Milo filed a lawsuit against Simon & Schuster for a breach of contract, for $10,000,000. Dangerous is now on the New York Times Best Seller List.